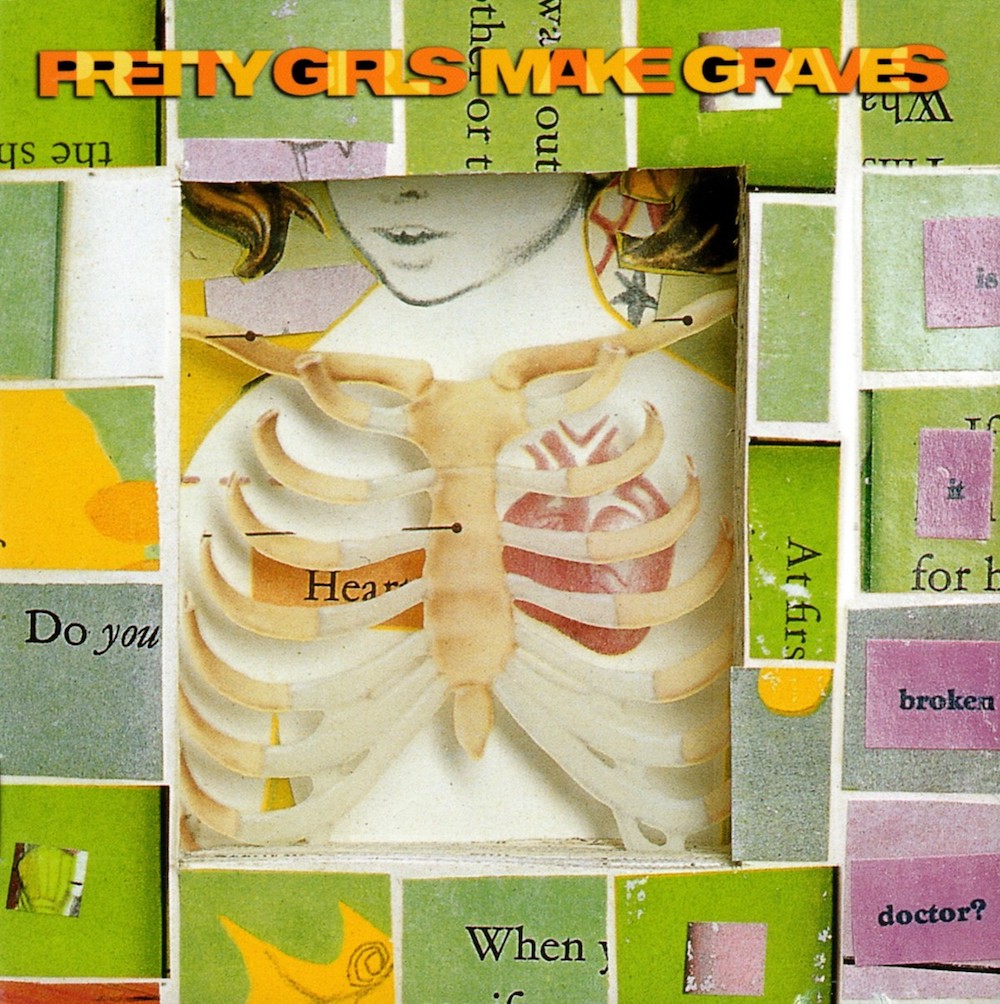

- Lookout!

- 2002

The term "indie rock" used to mean something different. As a genre designator, "indie rock" was always pretty useless. The vast majority of recorded rock 'n' roll comes out on independent labels, and there's never been much of an aesthetic through-line uniting even the stuff that actively embraces the whole "indie" idea. But "indie rock," as a term in common use, didn't always connote upwardly mobile bookish tweeness. That probably happened sometime in the mid-'00s, when a certain form of NPR-friendly Decemberism became a dominant strain of American underground rock. Maybe this was the Pitchfork effect. (If it was, then I'm as complicit as anyone else; I wrote for Pitchfork at the time.)

Before that definition took hold, though, "indie rock" was a term with a certain set of associations -- the smell of cheap spilled beer, the sensation of zine newsprint rubbing off on your fingertips, the horrible skree where you weren't sure whether the warehouse noise band was just tuning up or whether the set had actually started. Those associations are long gone. Good Health, the excellent debut album from the Seattle band Pretty Girls Make Graves, is one of the last, best artifacts of that time. Good Health turns 20 tomorrow, and that occasion makes for a decent round-number excuse to look back on the album, the band, and the era that produced both.

Pretty Girls Make Graves came together from the dissolution of the Murder City Devils, the chaotic and guttural garage-punk band that spent a few late-'90s years spreading the gospel of riffs and squawks and self-administered tattoos across the American underground before shattering into pieces just as their genre was finding a measure of popularity. Once, in college, I turned down a chance to see the Murder City Devils open for At The Drive-In in Buffalo. This would've meant a couple of hours in my friend's car, both ways, on a Wednesday night, when I had class in the morning and an all-night security-guard shift the next day, and my decision meant that I missed my shot at seeing two different great bands as both of them were in the process of gloriously flaming out. Bad choice. I regret it. Sleeplessness is temporary, and rock 'n' roll memories are forever.

Around the time that the Murder City Devils were in the process of breaking up, bassist Derek Fudesco formed Pretty Girls Make Graves with four Seattle acquaintances, some of whom had played with Fudesco in short-lived punk bands like Area 51 and the Death Wish Kids. Pretty Girls Make Graves took their name from a Smiths song, which in turn took its name from a Jack Kerouac quote. Fudesco might've been the best-known member of Pretty Girls Make Graves, but the most important was Andrea Zollo, a hugely charismatic singer who screamed a lot but whose presence was still commanding when she was relatively quiet. The new band hit the ground running, and they released their debut 7" "More Sweet Soul" b/w "If You Hate Your Friends You're Not Alone" as part of the Sub Pop Singles Club in October of 2001, a week before the Murder City Devils played their last show.

Before 2001 was even over, Pretty Girls Make Graves released their self-titled four-song debut EP on Dim Mak Records, the label founded by future festival-headlining cake-throwing EDM megastar Steve Aoki. Dim Mak, which now exists in a very different form, started out as, more or less, a punk label, putting out records from bands like Cross My Heart and Planes Mistaken For Stars. Within a few years, Dim Mak would hit gold with the Kills and Bloc Party and the shift to blog-house, but Pretty Girls Make Graves weren't a part of that.

Pretty Girls Make Graves hadn't even been a band for a year when they dropped their full-length debut. Good Health came out on Lookout! Records, the Bay Area punk institution that had introduced the world to Operation Ivy and Green Day but still found a way to eventually go out of business. By the early '00s, Lookout! had parted ways with founder Larry Livermore and lost its identity as the defining Gilman Street-adjacent pop-punk label, but the Lookout! roster was still crazy strong -- Ted Leo And The Pharmacists, the Donnas, the Oranges Band, Ann Beretta, the reunited Bratmobile. Since Pretty Girls Make Graves were basically a punk band, they fit right in.

Good Health is a great punk record and a great indie rock record; in 2002, those two things could be one and the same. The album's sound is a passionate herky-jerk mess. In the video for opening track "Speakers Push The Air," you'll see plenty of the signifiers of early-'00s hipster culture -- all the tight T-shirts and floppy haircuts that typified that particular moment. (Like "indie rock," "hipster" meant something different in 2002, though even then it carried the vague sense that you didn't want anyone calling you that.) But there's no distance in "Speakers Push The Air," no sense of pose. Instead, Pretty Girls Make Graves' biggest song is an earnest and fiery ode to the power of music itself: "Life's complications and frustrations, they disappear when the music starts playing! I found a place where it feels all right! I heard a record, and it opened my eyes!" They really meant it, man.

That same earnestness extends to the rest of Good Health, as Good Health is also a great emo record. There's a song about being on tour and missing someone who's back at home. There's a song about the romance of finding someone and running away from your lives together. There's a song where the only lyric is about "trying not to fall in line" -- back in the time when not falling in line still felt like some kind of option for idealistic young people. (Internet-era capitalism beat those notions out of most of us real quick.)

The sound of Good Health is fast and urgent and adrenaline-charged, with Zollo and the rest of the band shouting back and forth at each other. But it's also rich and dynamic. The flinty, trebly guitar parts wrap themselves up into tight balls, and the occasional organ-bleats recall Mates Of State, fellow early-'00s yearners for transcendence, more than anything resembling garage rock. On Good Health, tension and release are one and the same. The album burns itself out in 28 delirious minutes, and it's enough to leave you breathless and stirred.

The music on Good Health sounded closer to the tangled-up post-hardcore coming out of Dischord in that late era -- Q And Not U, Black Eyes -- than to most of the retro-minded indie and garage rock that was getting critical buzz at the time. Lyrically, Good Health might as well have been hardcore. "Speakers Push The Air" is an anthem about staying connected to the youthful rush of energy that music ideally should give you. In its message, "Speakers Push The Air" is essentially the same song as "Can We Start Again," the big anthem that Boston hardcore heroes Bane included on their own debut album a few years earlier. The music sounded different, but Bane and Pretty Girls Make Graves were essentially coming from the same place.

The one time I saw Pretty Girls Make Graves live was a few months after Good Health came out, when they played at the Siren Festival, a free show at Coney Island that my future employers at the Village Voice used to put on every year. In 2002, the Siren Festival was full of bands that were on their way to being famous: Modest Mouse, the Shins, Liars, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, the Donnas. Pretty Girls Make Graves looked and sounded as good as any of them, but their music wasn't cool like the Yeah Yeah Yeahs or soothing like the Shins. Instead, it was jittery and sharp-edged and galvanizing. Musically, Pretty Girls Make Graves had more in common with New York's own Les Savy Fav than with any other band on the bill. But Les Savy Fav made a whole art-stunt out of being entertainers; Tim Harrington was a sort of ironic vaudevillian. Pretty Girls Make Graves were a whole lot more sincere than that. They came off as the punk band that they were.

On the strength of Good Health, Pretty Girls Make Graves signed to Matador, which probably isn't the best label for any band that has anything remotely in common with Bane. When Pretty Girls Make Graves released their follow-up album The New Romance in 2004, Matador's big meal ticket was Interpol, and Pretty Girls Make Graves had basically nothing in common with that band. The New Romance is a dope-ass record -- maybe even a better album than Good Health -- but it didn't exactly turn Pretty Girls Make Graves into a buzz band. They followed The New Romance with another album in 2006 -- one that I don't remember at all -- before breaking up a year later. Different Pretty Girls Make Graves members moved on to different projects: Jaguar Love, the Cave Singers, the reunited Murder City Devils. Andrea Zollo became a hairstylist, and she's been dealing with some medical problems lately; her GoFundMe is here. As far as I know, there's never been a Pretty Girls Make Graves reunion.

In a sense, the music on Good Health is deeply tied to its historic context; that kind of stressed-out angular post-hardcore was all over the place in the wave of At The Drive-In. But Pretty Girls Make Graves never felt like a cynical attempt to cash in. They just made intense, passionate music that left its impact on the people who heard it. I'm not going to sit here and tell you that they should've been stars; who am I to make that kind of claim? But they made great music, and they meant a whole lot to me at a pivotal personal time. They were, in their moment, exactly the band that I wanted to hear, and that visceral connection remains. I have no idea how Good Health might sound to someone who wasn't there at the time, but for those of us who were, Good Health is still a sharp enough shock to remind you what the music meant. And nothing else matters when you turn it up loud.