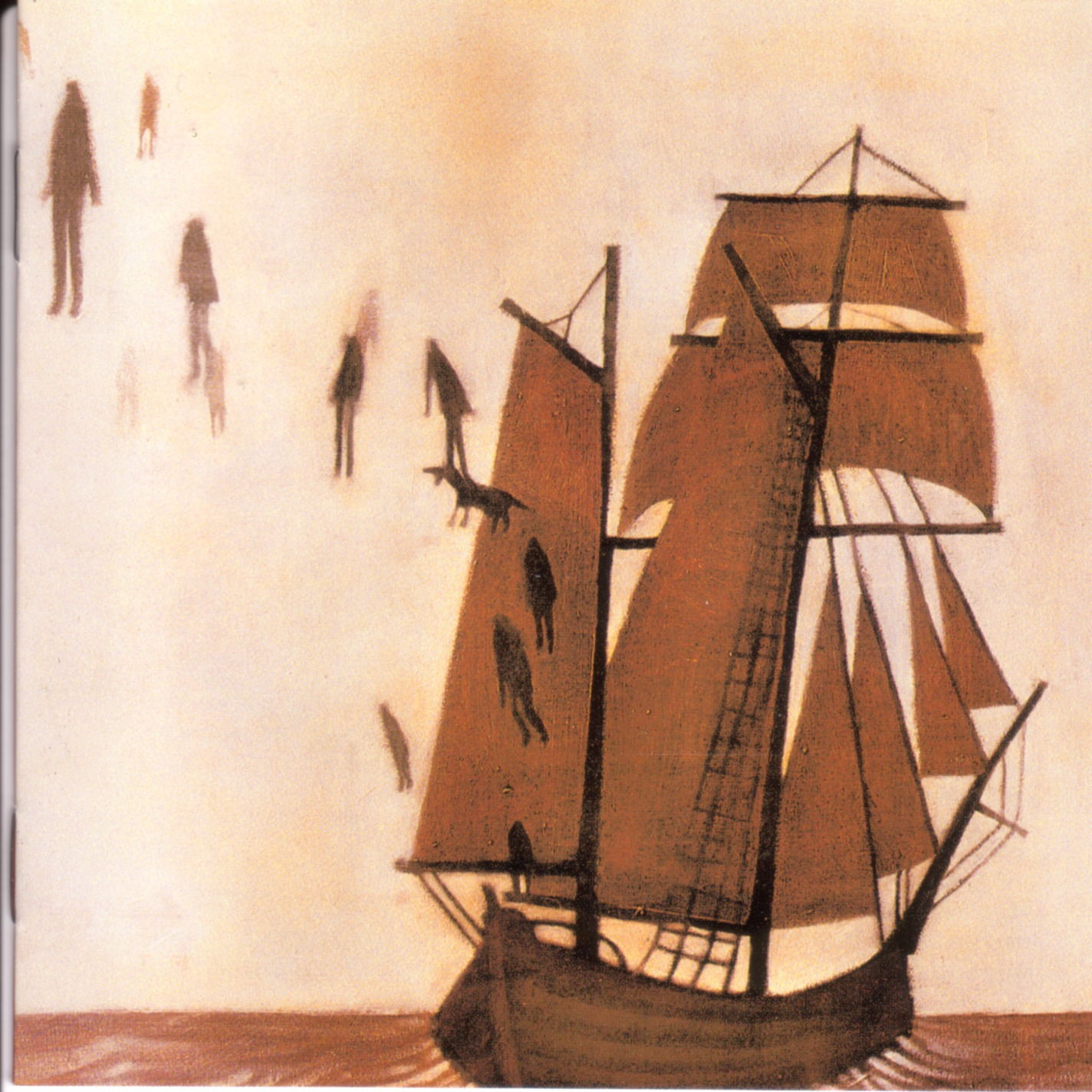

- Hush/Kill Rock Stars

- 2002

Christmas was nearing. Alexander I was dead. It had happened fast -- a case of typhus on a tour through the south of the country -- and now power was up for grabs in Russia. For a few weeks there, no one seemed sure who would take over as tsar. Alexander's rightful successor, his younger brother Konstantin, had privately declined his place in the line of succession two years earlier because he was living in Warsaw, having married the Polish noblewoman Joanna Grudzińska. But Konstantin's abdication was not a matter of public knowledge; Alexander had requested it be kept secret.

Not even Nikolay Pavlovich, the next brother in line, was aware that Konstantin had opted out, which led to an absurd and ultimately tragic sequence. Immediately after Alexander's death in November 1825, Nikolay swore allegiance to Konstantin, as did most of the military. Konstantin promptly wrote to inform Nikolay that he wouldn't be taking the job, so Nikolay assumed the throne, becoming Tsar Nicholas I. He was still in the process of building a coalition ahead of his formal confirmation when a secret populist faction sprang into action, arranging secret meetings and forging fragile alliances.

The Northern Society, based in Saint Petersburg, wanted Russia to become a constitutional monarchy, whereas their counterparts in the more radical Southern Society out of Tulchin, Ukraine sought to overthrow the monarchy entirely and turn Russia into a republic. Still, even for the moderate reformers, the temporary uncertainty about who would become tsar seemed too timely an opportunity to pass up. By early December, military officers Nikita Muraviev, Prince Yevgeny Obolensky, and Prince Sergei Petrovich Trubetskoy had hatched the conspiracy: They would gather 3,000 troops in Senate Square as Nicholas was sworn in the day after Christmas, announce that they refused to acknowledge him as tsar, put forth Trubetskoy as "Dictator" instead, arrest members of the royal family, and force the senators to recognize the pro-serf "Russian People's Manifesto."

The morning of Dec. 26 -- or Dec. 14 according to the Old Style calendar -- the rebel soldiers assembled, but Trubetskoy's assistants A.I. Yakubovich and A.M. Bulatov surprised them by refusing to supervise their coup d'etat. The uprising was thrown into confusion before it had even begun. By the time the first wave of troops showed up at Senate Square, it was 11AM and the Senate had already confirmed Nicholas as emperor and departed. Trubetskoy decided not to bother showing up to fight a losing battle, but his rebellion carried on without him. Citizens in the tens of thousands gathered to support the insurrection, but the rest of the military aligned itself behind Nicholas, much to the Northern Society's dismay. The reformist contingent found themselves surrounded, outnumbered, and stuck in a standoff.

At 3PM, the rebels elected Prince Yevgeny Obolensky as their replacement "Dictator," but by then their movement had already missed its moment. Two hours later, having grown impatient with negotiations, Nicholas ordered his army to open fire on the rebel forces, killing 80 and sending the scene into chaos. Many arrests ensued, leading to sentences ranging from death to prison to exile in Siberia. Nicholas consolidated his power. The so-called Decembrist revolt had ended with both a bang and a whimper.

In the early 21st century, a similar (but admittedly lower-stakes) power vacuum was in place in the realm of quirky indie folk-rock with an historical bent. Reacting against the overwhelming success of Neutral Milk Hotel's In The Aeroplane Over The Sea, Jeff Mangum had quietly vacated his place of prominence at the end of 1998 -- no official breakup or retirement announcement, just a retreat into the shadows before anyone realized it was over. The king was dead, as a certain bespectacled singer-songwriter might put it. As the early years of the next millennium unfolded and Aeroplane took on its mythic status, a number of contenders for NMH's throne emerged, and many of them became wildly successful. But the first to enter the arena -- before Beirut and Okkervil River and Arcade Fire and whoever else -- were the Decemberists.

Not that Colin Meloy ever explicitly set out to emulate Neutral Milk Hotel. Tarkio, the band he'd been leading as a Montana undergrad in the late '90s, practiced a primitive version of the Decemberists sound so user-friendly you'd more readily mistake it for Jars Of Clay than "Two-Headed Boy." In 2000 he relocated to Portland and ended up scoring a silent film with Nate Query and Jenny Conlee, former bandmates in a now-defunct project called Calobo. With the addition of drummer Ezra Holbrook and multi-instrumentalist Chris Funk -- an unofficial member for the first several years despite his significant contributions -- they launched the Decemberists: a reference to the failed uprising in imperial Russia, chosen to evoke the "drama and melancholy" of the final month of the year. After getting their feet wet with the 5 Songs EP in 2001, they released their debut album Castaways And Cutouts 20 years ago this Saturday via Portland's own Hush Records.

The Decemberists' music has evolved a fair amount over the years, but they arrived with a well-defined ethos, one summed up succinctly enough by their bio at All Music Guide: "theatrical, hyper-literate pop songs that draw heavily from late-'60s British folk acts like Fairport Convention and Pentangle and the early-'80s college rock grandeur of the Waterboys and R.E.M." You'll note that only one band from Athens, Georgia was listed there, and they have nothing to do with E6. Yet when Kill Rock Stars reissued Castaways And Cutouts in 2003 -- with its accordions and shanties and odalisques and legionnaires, and (maybe especially) with its opening track about a stillborn girl whose ghost is still wandering parapets and clinging to petticoats 15 years later -- some listeners could not ignore the way Meloy's songwriting echoed Mangum's fixation on the Old World's eerie beauties and horrors.

One of those people was Eric Carr, who, as the critic assigned to write up the album for the increasingly influential webzine Pitchfork Media, was empowered to shape the early public understanding of this group. As a college freshman whose biases were profoundly impacted by what I read on Pitchfork, he certainly impacted my own perception of the Decemberists. Carr began his review like so:

If Jeff Mangum had never been born, Colin Meloy could have assumed Jeff Mangum's current status as indie rock's consummate pop songwriter freak. Which, of course, would mean some other wild-eyed kid from Montana would have had to be Colin Meloy. The Real Meloy, in this Trading Places-themed Twilight Zone, would have filled in for Mangum's nasal warble and given the world the sweet gift of In The Aeroplane Over The Sea with his band Neutral Milk Hotel, while New Guy would front a band named, say, The Decemberists, who would shamelessly mine the sparkly folk-fuzz (sans-fuzz) of that most lauded of Elephant 6 bands. The Decemberists would be a tad poppier, and maybe a tad sweeter than their key influence, but fronted by a voice so close to Mangum's that few could tell the difference. Some say this may even have actually happened. Some say it's happening right now.

Mind you, this tirade kicked off a review anointing Castaways And Cutouts as Best New Music. Even a skeptic could see Meloy and his band were on to something. And although Carr was hardly the only one to compare the Decemberists to Neutral Milk Hotel, there were those for whom the similarity was cause for outright celebration, like Jesse Jarnow at Salon, whose wholehearted love for the album and its 2003 sequel Her Majesty The Decemberists almost made him feel like he was cheating on Aeroplane:

I have an instant affection for Meloy and the Decemberists. And the reason for my instant affection, which is admittedly unfair to all parties, is that they uncannily resemble an entirely different band: Neutral Milk Hotel. And it's not that the Decemberists merely remind me of Jeff Mangum's now-defunct outfit -- they sound like them right down to the smallest of mannerisms: the nasal faux-English accent, the ragtag marching rhythms, the fascination with the Old World, the songs about dead European girls. It's forgivable, because it doesn't sound exactly intentional. It also makes me open myself to their new album more than I would otherwise. Maybe too much.

Meloy might have brought the comparisons upon himself, but Castaways And Cutouts was good enough to transcend them. From the beginning, he was a great songwriter, weaving his menagerie of flawed characters and striking images into tight little tunes. From the beginning, they were a great band too, able to pull off so many moods and feels within their distinct sonic vocabulary, floating one moment and surging the next. And anyhow -- despite some obvious degree of resemblance to that other band, especially in the way he pushed his nasal tenor into the high notes -- Meloy was more geek than freak, more interested in crafting bookish folk-rock for unapologetic nerds than roiling psychedelic visions. He had his own thing going on.

That thing was remarkably soft, both in the album's more upbeat moments (the jaunty "The Legionnaire's Lament," the jubilant "July, July!") and at its most somber (the pedal-steel serenade "Clementine," the glittering slowdrift "Cocoon"). The more theatrical impulses were in place from the beginning, most obviously on "A Cautionary Song," a sparse Eastern European folk stomper about a sex worker in a shipyard. (That one lays it on a little thick.) The proggy tendencies were there too, as heard in the swinging, organ-powered "Odalisque" beat switch, the one moment on which Castaways And Cutouts can be said to truly rock. But even if they were already performing in old-fashioned costumes, the Decemberists were not yet a band who'd have whole festival crowds hunching down and jumping up as part of some whale-oriented vaudeville stunt. On the whole, their debut presented a gentler, blearier, more homespun version of their aesthetic. Even its 10-minute finale "California One / Youth And Beauty Brigade" was far more solemn than the campy epics they'd later compose -- a prime example of the graceful beauty and prodigious whimsy that so charmed me back then.

On songs like the vivid, grief-stricken snapshot "Grace Cathedral Hill" and the windswept character study "Here I Dreamt I Was An Architect" -- my personal favorite Decemberists song then and now, mostly for the way Holbrook's tom-heavy drumbeat combines with the mantra-like electric guitar to give the music a contagious forward thrust -- the band dredged up such wistful splendor that it almost didn't matter what Meloy was singing about. Lines like "And just to lay with you, there's nothing that I wouldn't do/ Save lay my rifle down" were undoubtedly well-crafted, though, and lyrics about paying off library fines suggested he knew his audience well. But for such a literary band, the Decemberists were great at evoking a vibe. Funk and Conlee's accompaniment -- him on pedal steel and theremin, her on piano, Hammond, Rhodes, and accordion -- gorgeously shaded in the group's acoustic folk-pop core. Meloy was as skilled at writing hooks as thinking up vaguely disturbing old-timey premises. In the end, when he beckoned to his fellow outcasts, "Come join the youth and beauty brigade," the invitation was attractive.

A lot of people took him up on it. The Decemberists became a wildly popular touring act with an accomplished catalog, and their brand of quirky folk-pop helped to define the sound of the next decade-plus in the indie and alternative realm, trickling down to even more accessible descendants. You can probably draw a line from their substance and presentation to the far less respectable stuff that took over the world a decade later, the Mumfords and Lumineers and Of Monsters And Mens of the world. And if that seems like an ignominious legacy, well, at least the revolution the Decemberists started was far more successful than the one that gave them their name.