We've Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

When you talk about music lifers, Tommy Stinson certainly qualifies. The Minneapolis native joined the Replacements as their bassist when he was a teenager, playing alongside his guitarist older brother Bob. That gig set him on the path to a decades-long career that's found him forming and fronting several bands (Bash & Pop, Perfect), joining several established rock bands (Guns N' Roses, Soul Asylum), maintaining a solo career, and collaborating with a number of other artists.

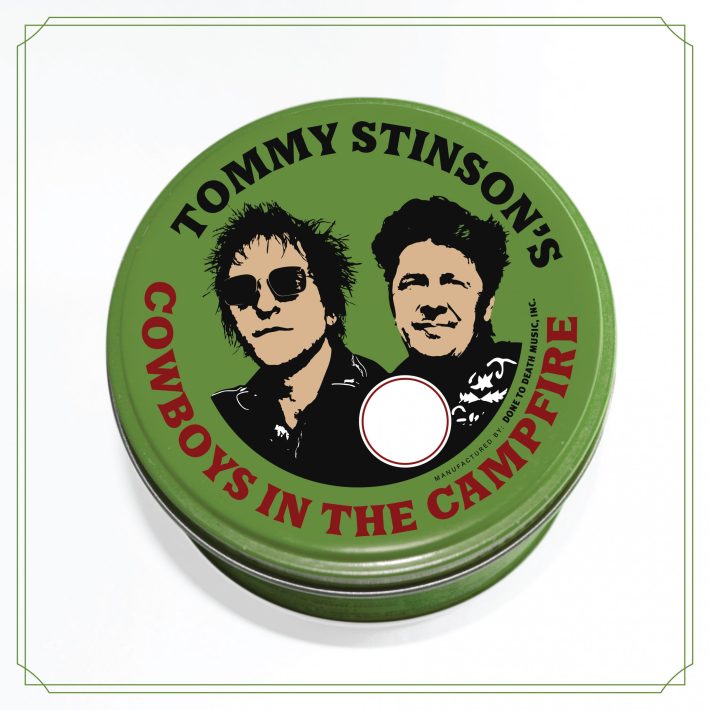

Today, one of his other ongoing concerns, Tommy Stinson's Cowboys In The Campfire, are releasing their debut album, Wronger. It's a lovely, thoughtful record steeped in classic country and acoustic folk, with flourishes such as horns, pedal steel and ornate backing vocals adding depth. Stinson's voice is perfectly suited for the music — weathered like a faded leather jacket, and brimming with emotion.

Stinson initially formed the band with Chip Roberts — who happened to be his ex-wife's uncle — during a period where he was living near Philadelphia. "He came up with his name Cowboys In The Campfire [and] we talked about, 'Yeah, let's go do some dates sometime,'" Stinson says on a video call from his house. "I was still traveling with Guns N' Roses at the time. I was still even playing in Soul Asylum, I think. I was all over the place. And then one summer came up and Guns was off, and Soul Asylum, I might have been done with that gig. We're like, 'What are you doing this summer?' And he's like, 'I ain't doing anything.' And I said, 'Well, I ain't doing anything either. Let's go play some shows.'" Stinson laughs.

That casual vibe extends to Cowboys in the Campfire's touring M.O. — they've played in backyards, record stores and space in between — although their live shows are meticulous affairs. For this upcoming round of summer touring, Cowboys in the Campfire are adding a bassist (the awesomely named Chops) to flesh out their sound.

That's not all Stinson has going on — he's opening some dates for his old band Soul Asylum this summer, and after our chat, news broke that a boxed set of the Replacements' 1985 album Tim is coming this fall. In the meantime, however, he chatted about what he learned from being in Guns N' Roses, the impact of the Replacements' reunion and just exactly how he ended up playing bass on the rock remix of Puff Daddy's "It's All About The Benjamins."

New Album Wronger With Tommy Stinson's Cowboys In The Campfire (2023)

I was surprised that this was the first Cowboys In The Campfire album — you've been touring so long with them. Why was now the first time to finally release a record?

TOMMY STINSON: Because we're a fucking couple [of] slow-ass old men. [Laughs.] That's the first answer. Chip and I were writing songs together from the moment I met him, 14 years ago now. [We started] doing [the band] anytime I had downtime and, in the meantime, writing songs in between.

The reason why it took so long is because we weren't really planning on turning it into a full thing until suddenly realized we had over half a record of stuff. It wasn't Bash & Pop-like. It wasn't solo stuff, per se, because I approach my solo stuff differently. And it took that long to finally go, "Alright, well, let's make it a record."

It was probably the beginning of 2020, 2021, somewhere in there, that it was really starting to come together as a record. Fat Possum was going to put it out, and they were liking the stuff we were playing them. That whole deal fell apart last November for just differences of what we should be doing, and I wasn't going to fold on it. But finally we have a record and [we're] putting it out. And, yeah — the world is our oyster.

When you and Chip first started writing songs together, where did you find commonalities? What made you such good songwriting partners immediately?

STINSON: He's a little bit older than me, but we grew up in the same rock 'n' roll scene, in a way — although he leaned more towards the local guitar-slinger-hero guy from Philly that would play with a lot more country acts and George Thorogood people and Hooters. He was friends with all those folks and would play with those guys. He had different things in Philly going on for his whole youth into adulthood. His most notable band was with his brother John, was the the One-400's. They were in that '80s rock 'n' roll rockabilly country-ish kind of thing. We got along. There's a lot of — I hate the term singer-songwriter, but there's a lot of that element in my history of music, from the Replacements days and all that. So we're a good fit together.

It's funny that there's the intersection between country and alt-country and rock and punk — it's all pollinated, especially now. In hindsight, we see that more. It's less separated and segmented than maybe it used to be.

STINSON: I used to like it when it was like, "Okay, this is the No Depression scene." [Laughs.] And then there's everything else. Now it's Americana. That term drives me batshit — it sounds so Republican, you know what I mean? I can't even be bothered with playing Americana. I'm more on the Willie Nelson side of things, Glen Campbell's side of things.

I liked that John Doe's on the record, because he's very similar in that sense, and his career has really unfolded a lot like yours. He's gone in so many different directions.

STINSON: Exactly. And we just saw him the other night and [it's] exactly what you just said. Our music always starts with the singer-songwriter thing, because we all kind of write with our acoustic guitars originally to make a song, whether it turns into a rock song or not. But when you strip it down, [it's the] same shit — same genre, same thing in a way.

What's your favorite song on the new record? What song means the most to you?

STINSON: The one that I've been really liking a lot right now is called "Hey Man." And it seems to be, when I play that live, it has a certain thing that happens to it that I can feel people are paying attention in a different way. It's got a bit of an anti-war undertone to it — I didn't want to be real obvious, and I don't want to get real political about it. I'm not that guy. I flirt with ideas and I let you, as the listener, come to your own understanding of what's in the song. I try to keep it pretty open for debate and discussion. I like it that way; it gives me something to work with. But it comes off pretty good live and people seem to really like it.

This project is so portable, I love all the places you play; it does seem like just such a fun thing. You play in unorthodox spaces and show up wherever.

STINSON: The beauty of what I get to do now — and I say that in all reverence, I get to do it. I'm lucky to be able to get to do what I do in so many ways. But it is on our own terms. We can go out and play as many gigs or as few gigs as we want, depending on how we're feeling about it.

This year I'm going to be really, really busy, because I had some bumps in the road last year — I had to had to get a new hip. [Laughs.] And now I'm ready to hit it and have a good summer out here. But we get to do it on our own terms and play the gigs that are offered and the gigs we want and bring it to the people's front door if we want.

Playing On Tulsa Jacks' Walter's Vacation, Which Also Featured Bob Mould (1982)

On Discogs, it notes you played on a cassette back in 1982 with the Tulsa Jacks. Do you have any recollection or any strong memories about that?

STINSON: No, not at all. But someone else brought that up not that long ago — but long enough ago that I can't remember. Someone played me the song and I go, "Wow, I played on that?" 1982 — I mean that's 100 years ago, back in the 1900s. [Laughs.]

Is there anything that you've done in your career that you wish had gotten more attention or wish had taken off or gone in a different direction, music-wise?

STINSON: Everything. I mean, you always would like to see everything become successful and the world love it. But no, nothing in particular — except all of it. And you know what? We all have our place in this grand scheme of things. I'm cool with mine. I'm lucky to still be able to do what I do on my own terms. Make a bit of a living at it. It ain't always easy, but I still get to do it — and I'm doing it. People still like to come see me, which is great. I still like the writing process.

The older I get, the more adventurous I'm actually becoming, because I'm not tethered to anything sound- or program-wise. I can just do what I want. Over the last few years [that] has really made me experiment more and getting me into wanting to take that further.

Is there anything in particular that stands out?

STINSON: I'm not going to go fucking totally grandiose or anything in any sort of way, but just more instrumentation, different things that I'm interested in and different stuff. Why not? I can do whatever I want. Whether people are going to buy it or not, it's never really been the motive for doing what I do — because you never know if anyone's going to buy it anyway.

Bash & Pop's Friday Night Is Killing Me (1993) And Anything Could Happen (2017)

What was your mindset making the first Bash & Pop record?

STINSON: I started writing that record when we were in the end of the Replacements. And for all the things that were going on in our personal lives, Paul [Westerberg] and I both, there's a lot to that. It was a growing period, personally, but also an exploding your life period in that, when we were both in a particular spot.

As the Replacements were coming to an end, a lot of that stuff was written about those times, both personal and professional. I mean, we had spent 10 years humping the pavement, doing all the things — some of them to the best of our ability, some of it self-sabotage in a lot of ways. It was trying to figure out, "Okay, now how do I go forward from this?" That record has a lot of that in it, a lot of questions about, "Why am I doing this? [Laughs.] It's not working for the Replacements. Why would it work for me?"

Except that the thing that came to me — we knew pretty much before we made All Shook Down that Paul wanted to really be more in the producer chair. Even though we had had [All Shook Down producer] Scott Litt, he really wanted to get more into it and get more of his ideas across. And he did a good job on that one, better so than Don't Tell A Soul. I think Paul had that idea for those two records, but it worked better on All Shook Down, for whatever reason, as far as getting the songs to portray themselves the way they wanted to be.

Watching that process go down, I was in that mindset too — here's my batch of songs to do exactly that thing. It was a good way to start my process of wanting to do it. Because, ultimately at the end, we were pretty beat up. We admittedly beat ourselves up a lot, but it was ups and downs and heartbreak and all this stuff with how we did things. Easily at the end of that run, you could have gone like, "Aw, fuck, I want a job. A different job. Anything." But we both still loved playing music a lot and still had to come to terms with how and what.

Funny enough, it's taken me all these years to finally get to a place where I really do know why I do what I do, and it is because I do enjoy it. I like playing in front of people. I like the process. I've gotten more comfortable in my skin about what to do with that in the process of making records and challenging myself at every turn when I can. I feel like you always have to do that — push yourself a little more.

It makes sense though, because you were still really young when the Replacements split and Bash & Pop started. People forget that. Most people in their mid-to-late-20s are still just getting their first jobs and figuring out who they are.

STINSON: Yeah, exactly.

And you did that after growing up in public. In hindsight, you can be kinder to yourself.

STINSON: Exactly. I didn't learn how to get kinder to myself until recently. [Makes whew sound.] But yeah, no complaints. No complaints. It's all part of the deal, right?

When Bash & Pop came back a few years ago, then, was it just the songs you were writing? Was it unfinished business? What led to that?

STINSON: A little of both. I had amassed a bunch of songs that I was recording in my studio. I was going back to square one. At the end of the Replacements' run, what we did — which was what everyone started doing in the late '80s — is starting to… With the advent of digital recording and sequencers and shit like this coming into the fray, people were starting to experiment moreso in a way which became time-consuming. I guess in our case, we were given the leverage to screw around the studio longer than we probably should have.

Don't Tell A Soul’s a great example of that. I think we farted around too much. I mean, the songs were the songs. There was a vision that Paul had — and others like Tony Berg, when he started — of trying to do this thing with us when we were pretty much a blue-collar rock 'n' roll band. Paul had designs on trying different things, but I don't know if he really knew how to verbalize what it was exactly, or even understand what it was he was looking for. But we messed around too much.

Whereas cut to me in my own studio in my house over here, I got to a point where I was like, you know — I had my friends come up and play, and we cut those tracks live. I was getting a lot out of my friends, playing together, getting the vibe in the first couple takes.

I was like, "Shit, that's the way we used to make records when we first started," if you think about it. Think about the stories you've heard about the Stones, 150 takes of "Jumpin' Jack Flash" before they got the right take of that. You just think about, "Fuck no, I ain't doing that."

In the Replacements, we did that for a while, and it kills what is there in a song. You got the lyrics written; you've got the song structure pretty much written; you're waiting for this great feeling to happen. There might have been other reasons the Stones or the Beatles did things like that. I don't know if any Replacements song ever benefited from being played fucking 50 times at any given point.

But I learned that over the years that I like the idea of a band and a group that you play the song, you learn the song, you're excited about the song, push record. Be done with the song and get all everyone's bits when they're so excited.

I was talking to Lisa Loeb about this the other day — the more you keep trying to find that other thing, [it's] diminishing returns. Unless you're really swapping instruments out, trying it a different way. Trying it different ways, that I get.

So, that Bash & Pop record came from me doing sessions in my studio — quick sessions, because I only had [drummer] Frank Ferrer around for a short time when he was in town, because he was still in Guns N' Roses and stuff at the time. Actually, we were both still in Guns N' Roses, but I'd get him up here to play some stuff once in a while.

So it came together as a band record, because I was getting all the tracks for it in a live setting and I was liking it. That in turn became more conducive to becoming a Bash & Pop record, because that's how I did that first Bash & Pop record. [On that one] I did a lot of stuff live with [drummer] Steve Foley in the studio, at least the basic tracks of it anyway, to get the best takes.

I'm totally back to square one with this shit. I ain't doing 50 takes at anything anymore, no matter what. Maybe if I'm still writing the vocal melodies, things like that, it'll take longer. But for the most part, that's why that record turned into a Bash & Pop record, because it was more of a live-band-feel record. I owned the name still and I thought, "Well, shit, this is like that record." I hadn't listened to that record in ages. And I'm going, "Well, these make sense."

That's what I loved about it is that it had been almost 25 years and it's like no time had passed. It was like you picked up right where you left off.

STINSON: Yeah, yeah. It's the rock 'n' roll heart business. It's still there. It's still in me.

Playing Bass On The Rock Remix Of Puff Daddy's "It's All About The Benjamins" (1997)

How did you end up playing bass on this song?

STINSON: Funny story that one. My band Perfect was playing shows at Coney Island High in New York, which is Jesse Malin's old club. [Jesse's] one of my dearest friends on the planet still. He would call me up once in a while [and be] like, "Hey, man, you guys want to come out and play a gig? We'll get your airfare, pay you and put you up." I was like, "Why not? I got nothing else going on next weekend." [Laughs.] Usually, it would be like a month or so in advance.

But we'd go do these gigs in the city. I was living in LA at the time. The guy that was working for Puff Daddy's label, Bad Boy Records — this guy was a fan of mine, Replacements fan, all this stuff. We're hanging out a little bit. At some point, it came up that he was trying to get us to sign to Bad Boy. It just didn't turn into a serious offer or whatever for the rest of the company.

But they had "It's All About The Benjamins." The song was already on MTV, already a single, the pre-remix version. And they weren't happy with what it was doing, so they wanted to do a rock remix, because that was becoming a thing. So we went in the studio and we wrote the chorus for it, which is that "It's all about the benjamins" part. That's us, that's my band and us doing that. The whole chord progression, all that came from us.

So, we did that, threw that out there. [And] he threw it out to 50 other fucking people, as you can tell from the credits on it. Everyone did add a little bit here, add a little bit there. But what they really did was they just capitalized on the fact that he was so famous that he'd get anyone from Dave Grohl, Tommy Stinson, to whoever the fuck — Rob Zombie — to fucking play on his remix. And if nothing else, all these people's names might help this be a bigger single than it was already, being that wasn't enough for them.

So it became a bigger single for 'em with all these names. But that's me and my band Perfect at the time doing that. Then it's becoming so big, [they told us] "We want to make a new video of the same song." They'd already had video for a year out. It was just so goofy.

We ended up doing this video. It was like a million dollar fucking video budget at Burbank High School in the summer. It was just bananas. Lil' Kim, who was super funny and sweet for all the nasty shit that'd come out of her mouth, [laughs] she couldn't have been sweeter. But yeah, we ended up doing that whole thing. Yeah, pretty wild, kind of funny. And they ended up not using anyone from my band but me because — what was the kid that played drums in the video? It ended up being a movie star.

Jason Schwartzman, right?

STINSON: Jason Schwartzman, he was the guy. They wouldn't let any of my band guys in there because they wanted Jason Schwartzman to be there because he was doing Phantom Planet. And then suddenly after that, he turns into a big movie star. I got the raw end of that deal.

And they actually had us do another remix for Ma$e after that. I got to be honest, we did a way cooler job on that track. They didn't end up using it, but we stripped it down. We ended up doing a more of a Sly And The Family Stone kind of thing. We were super, super stoked on it, because it turned into a really great track, for another track that really had no melody going on for it. We added a lot of melody and did background vocals and all that stuff. We were so pumped. Then they were like, "Nah, we don't need it now. We got so-and-so to do this thing." I don't think it ever made quite the stink as "All About the Benjamins." But yeah, it was pretty funny.

Did it ever come out?

STINSON: It never came out, no. Someone's got a piece of it somewhere. I don't know who.

That's such a drag, to spent so much time on that and just have it be languishing.

STINSON: Actually, shit, [one-time Replacements manager/Twin/Tone Records founder] Peter Jesperson might have a copy of that, because I think we did that while we were still on Restless Records actually. I'll have to ask him. I got to call him anyway. I owe him a call.

Did you have other things in the vault then? Do you have anything else that got away, that you lament you wish you'd gotten out there?

STINSON:[Laughs.] Which band?

[Laughs.] That's true. Fair.

STINSON: Yeah, no, I got little things all over from everyone that I've made songs for that will come out at some point.

Playing Bass On MOTH's Provisions Fiction And Gear (2002)

I love that record and I somehow did not realize you played on that.

STINSON: Sean Beavan was producing Guns N' Roses at the time when I met him. Actually, no, I was in Guns N' Roses when Axl brought Sean on. We became fast friends, him and I, through all that. He picked up that [MOTH] record and wanted me and Josh to play on it. The fucking songs were great. Great story about that kid, the singer from MOTH — Brad Stenz. [There was a] dark story behind that kid. He comes from some crazy stuff. But made a great record and we had fun making that record, Josh and I and Sean. I was bummed it didn't go further. It had some really, really good songs on it.

Working With BT On Emotional Technology (2003) And The Movie Score For Catch And Release (2006)

How did working with BT come about?

STINSON: Again, another funny thing. So, Paul was working on a movie for Sony. What was it called?

Was that Over The Hedge?

STINSON: No, no. It was one about the bear. [Laughs.] He did a movie for Sony. I went and played on it. He was in LA [and] he asked me to come play right on this track. It was a rock track.

Open Season?

STINSON: Open Season, that whole franchise. So, he had me come play on that record. I can't remember what track even. The woman who hired him and I became fast friends, just from the session. We had some people in common. I already knew BT from my friend [current Guns N' Roses guitarist] Richard Fortus. I'd already hung out with him. We were pals already, friends.

So I get hired to do the movie score for Catch And Release. But they needed someone who had scored a movie before to work with me because I hadn't scored a movie before. So it was like, "Hey, how about you and BT do this?" I was like, "Sure." So we scored that together.

That was a fun project. A lot of that I actually did on my own with him, doing more of the technical and editing parts of what we were working on. I used his crew of people, mostly in the songwriting department. We would get together in his studio, and then I'd get together in my studio, go back and forth. I think he was pretty burnt on the movie scoring process at that point. He had done so many of them, and I think he was over it. So I did a lot of that with his crew. He was taking more of a backseat, but more of an executive producer thing in a way.

But one of the funnier things that came out of that was I get a call from him one day. He's in his studio and he's got Tiësto [and] Steve Perry from Journey. They're working on a track for this Tiësto record. [BT] calls me: "Tommy, we're working on this track. We really like it, but can you come help us out? We need some lyrics and we just need help with it."

So I go over there — and I'm sitting in a fucking room with Tiësto, Steve Perry, BT. It's starting to turn into a nice song, but it's also happening in the middle of us finishing the score for [Catch And Release]. It got kinda dicey for a minute there where I'm working on this movie that he's basically washing his hands of a little bit while he's working on this Tiësto record. And he's got Steve Perry over, and he calls me to help work on this a little bit and help write some lyrics. It turned into a whole thing.

The song actually turned out to be pretty cool. It was pretty magical. And Steve Perry — I would've never thought anything of this until I'd hung out with the guy for a little bit. What an amazing character, and his voice was so operatic and booming. I'm like, "Holy shit, that's his fucking voice." It was really impressive. Then him and Tiësto got in some disagreement and it never came to anything. But I got to hang out with Steve Perry, and it was a really cool session.

We did end up finishing the movie soundtrack, which was what we were hired to do when all this other stuff was going on. But it was super, super cool.

After that, I lost track of [BT]. In his frustrations and being over the movie business, he lit a fire and left it. [Laughs.] If you know what I mean. He walked away from Hollywood in a way and went back to music his own way. But it was an interesting time. I mean, he's a fucking genius and I love him. To work with him — I mean he's way outer perimeter, above and beyond my school of music. His orchestrations and he's just crazy music genius guy.

I could see that Hollywood would be difficult, because from what I understand, the deadlines are so ridiculous, and there's so much pressure and so many different moving parts. Film scoring is such a different beast than anything else making music.

STINSON: Man, I loved the hell out of it. I was bummed that I've only done one. I've written music for other little things, but I really like the process, because they would have me change on a dime. I'd go, "Cool, you want sound like this instead of that? Awesome." I adapted and would try anything, because, one, I was green. I hadn't done it before, so I was like, "Fuck, this is fun." It's like wear different hats every couple hours. [Laughs.] It was cool. I I liked the process a whole lot.

That's good. We'll put that out in the universe — I'm a big believer in that. You'll get a phone call then.

STINSON: [Laughs.] "Tommy likes scoring movies. Call 1-800-Tommy-Scores."

Being In Guns N' Roses (1998-2014)

You mentioned doing multiple things at once. I'm impressed that you've completely overlapped so many times. You were in Soul Asylum when you were in Guns N' Roses. How did you balance doing everything then?

STINSON: Well, with Guns N' Roses, there was always a lot of down time. We'd tour — bang, bang, bang, bang, bang, and then not tour for big chunks of time. That gave me time to work on other records, do other bands, whatever. I didn't sign exclusively to them to begin with.

Oh, okay — you weren't on a retainer then.

STINSON: Yeah. [Laughs.] Well, originally, I was on retainer, but the retainer didn't keep retaining. So I was able to do other things and be like, "Well, I gotta make some bread here. I gotta do this other gig. Do you mind?" "Yeah, okay." So it worked out.

How was being in Guns N' Roses different from all the other bands you'd been in or fronted?

STINSON: Fundamentally, not at all when it really comes down to it. The one takeaway that I had from Guns N' Roses — which I still really can't say enough about this — I learned how to collaborate with people in a way that I would've never had collaborated with otherwise.

When I first joined that group of people — and it evolved a little bit over time, but all of us came from different backgrounds of music. Robin [Finck] came from Nine Inch Nails. Paul Tobias had grown up with Axl. Dizzy [Reed] had come from the LA scene. [Drummer] Josh Freese was the one that got me the gig. We'd all come from different places. Basically, Axl liked the different things that all of us brought to the table, and we wrote together in this way.

Cut to songs having pieces of all of us in 'em. To his credit — and he won't ever accept this as credit, I don't think, because I don't think he quite understood what he was doing — but Axl really was a great producer in this. He liked what all of us brought to the table and he found a way to, "Okay, I like this part here. I got a vocal melody here, but it needs to go. Maybe Tommy, try something like this, or Paul." He would get us to push forward in a way. It got to be a little bit time-consuming, but that's not why it took so long to make that record [Chinese Democracy], to be honest with you. He did a thing where he got us all involved in the music. There wasn't a song on there really that had just one guy writing it.

Even my own song — I brought a couple different songs to the plate and even that, he liked most of the song, but [would say] "Robin, what do you think?" And Robin would put his two cents in there. It was a really interesting way of doing it that I'd never done before in that capacity.

It was a really cool thing. Love that record for that reason. It has a lot of stuff going on in it. Whether you like the record or not, it took a lot of group effort to make it. Axl works that way, because I think in the past with the old band and that thing, everyone was vying for importance and vying for their song, blah, blah, blah. And he was the singer that had to decide, "Well, I like that one. This one needs work." But everyone was trying to get him to sing their song. That got to be troubling, so it was more like he had to find a way to make everyone work together. He's really great at that.

He hasn't made another record since, which I think it's unfortunate. He's got a lot of talent to work with right now to make a really great record.

I re-listened to Chinese Democracy before we chatted here. That makes the record make so much more sense now. I feel like maybe that it's been long enough now, people can listen to the record with less of the biases they had at the time and listen to actual music and get a sense of what's there. Because it is really interesting. It's dense.

STINSON: There is a lot going on in that record. I think people are going to realize it's a really great record down the road. It's going to be looked at historically as their best record, I think. You can look at the first records and stuff like that. They have the hits on them. But what is interesting about Chinese Democracy is there's a lot of him in those songs. He sang a fucking ton about his life, and about life in general in those songs, moreso than just a rock 'n' roll song about a fucking drug addict, that kind of thing or "Sweet Child O' Mine." There's a lot more going on there, depth-wise from him, mentally, than those earlier records.

There's a quote that's often attributed to Richard Fortus about that you were the "ultimate musical director" or "band leader" during rehearsals for Guns N' Roses. Did you view yourself that way?

STINSON: You know, I kind of had to. In the beginning, certainly, because we went through two different drummers. When Brain [Mantia] came on, it was clear that if I'm playing bass with him, I got to get on the same page with him, and we had to work hard at it, and then get everyone to play along and play the right parts had to be important. I think because I had the gumption to do it, I took on that role to some degree. I guess for all practical purpose, that became my role in a way unwittingly.

But someone had to corral everyone and make what came out make sense. I was able to do that. I was able to assert myself that way and get everyone, "You gotta play. This is the way it is on the record. This is what you gotta play. You can't be back there behind the beat. You can't be doing this, that, and the other thing." So I was able to pull it together that way, and I think Axl appreciated that as we went along.

What led you to be able to do that? Was it being in the Replacements? Was it fronting the bands?

STINSON: Well, I saw all these different characters and I saw what they played and what they sounded like, and I was able to go, "Well, we're here to play these songs for their fans, for the Guns N' Roses fans. We better get it down good if we don't want to get killed." So that was where I came from with it, was like, "Okay, our rhythm has to be fucking tight," because Duff [McKagan] and Matt Sorum or Steve Adler, they held down a pretty tight fucking rhythm section. I mean, when they were on, I should say. [Laughs.] The guitars fell into place in a particular way.

And the parts — you can come in there and think you know a Guns N' Roses song until you fucking break it down, and break down what Izzy was playing versus what Slash was playing versus what is going on. There's a lot there. There's a lot of fucking different parts in those songs, and you can't noodle through them. You can't just fuck around. You gotta nail it. In my mind, it was left to me, because I had the most experience of a lot of them. For my coming into the group later than the original bunch of guys — when I first joined the group, I had a lot more experience than all of them except for Dizzy pretty much. But yeah, so I just took it on.

You also got to sing lead a few times with Guns N' Roses, on your solo track "Motivation" and then a "Sonic Reducer" cover. How much fun was that then? Did you enjoy that?

STINSON: I had fun with it. I mean, it either that or do a bass solo. [Laughs.] I was not about to fucking sit up there and do a bass solo. But Axl runs around so much on stage, he needs a fucking break in every few songs to get his wind about him and do his thing to keep moving. That's why those shows are so long. But he wanted something out of me that I had to do, so I thought to do whatever came to mind.

The first time I did anything outside of anything, I think we did a fucking Sex Pistols song, I'm blanking on what it was right now. But he really liked that. He's in the talk-back as we're playing the song, "That's fucking great, I love that, blah, blah, blah." He's back in his quick-change booth, getting oxygen, getting water, whatever. [Laughs.] So from that point on, I'd switch it up every couple tours or whatever.

Awesome. What was the most fun Guns N' Roses song to play live from a bass standpoint?

STINSON: I always liked playing "You Could Be Mine." I always thought that was a really fun song. It's bass-heavy in a particular way, and [laughs] just had that rock 'n' roll thing that I could dig into pretty good.

Playing In Soul Asylum (2005-2012)

You played in Soul Asylum too. Is it true that you and Dave Pirner knew each other in high school when you were younger?

STINSON: Yeah. When I went into ninth grade at West High School in Minneapolis, I want to say he was a senior. We hung out. We all hung out — all of our friends and him and my best friend David Roth. His sister was a high-stepper, and she's gone on to become a pretty well-known movie director. All of us grew up in the bars, in the neighborhoods, at the parties, all of us together. I've known Dave since I was a kid. The funny thing is I'm going out playing shows with him in July. [Laughs.]

Oh, no kidding. That's awesome.

STINSON: Dave's going to do some Soul Asylum shows. I'm going to open up some of those, just for fun, on the West Coast.

Had you talked about collaborating before you joined the band then and played with them, or was it just because you were so busy and he was so busy?

STINSON: I joined Soul Asylum when Karl [Mueller] passed. His wife, Mary Beth Gordon, was actually my old girlfriend from when I was a kid. I guess Karl left a list of people he'd like to replace him if it was going to happen. I was on that list. So when they asked me, of course I said yes.

But I ended up going down to New Orleans to hang out with Dave and do some writing with him. In the midst of all that, we went in the studio and hacked out some stuff. There's one song that we did called "Engaged to Be Divorced" that I swear to God I'm going to fucking put out at some point. [Laughs.] He plays trumpet on it, which was great. I'm going to make him play it on the record too. It was a good little song.

But we collaborated down there in New Orleans. I went down more for a getaway, but he had a studio, and so we'd go mess around and we got a few songs out of it.

Officiating Weddings On The Side

STINSON: I was just in Cleveland recently — I officiated a wedding.

Really?

STINSON: Yeah — a new buddy of mine got married.

Have you done that before? Did you have to get ordained for the occasion?

STINSON: No, I've been ordained for years. I've done weddings before. A lot of time I do it for friends and people that want to do something fun and different. Yeah, I've been doing it for a while.

I would think songwriters would be very good for that. Because you have the writing background, you can make something unique and special, especially for friends.

STINSON: A lot of times what I do is I tell them to give me at least a quick synopsis of what you want said, and your wedding vows and all that stuff. And then I'll take it from there — I'll ad lib and talk about them, do my own bit. It usually ends up okay. Most of them are still married.

Promo Ad For The Goldbergs (2023)

I saw you recently filmed a promo for The Goldbergs.

STINSON: Yeah. [Laughs.] Well, they wanted to use a Replacements song. It started off as a funny thing. I hadn't seen the show, I gotta be honest about it. It was a big show, and they wanted to do a thing. I was like, "Sure, whatever." I did it, and then I watched the show and I was like, "Wow, that's funny." A lot of my friends had followed it and stuff like that. I'd been told it's a good show, so I checked it out. Random is what that was basically.

The Replacements Reunion (2012-2015)

When the Replacements did the reunion, did you notice a change after it ended in terms of attention on you or your music?

STINSON: Not really. I mean, we played in front of more people on that tour than we ever had [which] was the only thing really of note. It was a fun thing. There was nothing that was meant to spark any long-term reunion thing. I mean, we had fun with it. Getting Paul out of his fucking basement for a minute was a good thing. [Laughs.] We probably also scared the shit out of him. I don't think anyone's seen him since. [Laughs.]

Aww. [Laughs.]

STINSON: I don't know. I wonder about him. I wonder what he likes or doesn't like about the music anymore. It's been so long since I've connected with him in any way that I often wonder, "What the fuck is he doing over there? [Laughs.] Does he make any music down there? Does he want to put anything out anymore?" Maybe he's just got a job and is just happy not being in the biz anymore.

For me, I'm always going to do it until I can't. I guess that's just where I'm at in life. I still like the process. I still like the intrigue of, "Oh, I like this song. This one's really got a thing to it." Once you let them out the door, they basically go off into the world. Whatever happens to them, it's like your kids in a way. It's like, "Okay, good luck out there. Hope you do good." [Laughs.] I still enjoy all of it and I wonder what he does with any of it anymore. I don't even know.

There have been all the Replacements reissues on Rhino. Do you guys have to talk about that stuff? How does it usually work?

STINSON: They run all the stuff by us. The reality of all that is, Warner Bros., because they own the rights to it — although some of it, we're going to retain back after the 35-year clause I think — a lot of it, they could just do what they want with anyway. So, where we can, where I can — I don't think Paul really gets much into this; his manager Darren Hill does get involved a pretty good deal — they've involved us in repackaging to make it more than just them throwing shit against the wall without us. I think it's better that we're involved.

I like the idea of them coming to us and asking for input, because some of the things that they would probably do without our input, we wouldn't really want them to do. Some of this stuff is a bit of a bend on, "Ehh, it's possibly cringeworthy," but we have enough of a team of people involved with it — whether it's myself or Darren or Peter Jesperson or others in our sphere here — that like what's going on and have an opinion about it that as fans or otherwise, they think it's worth doing it.

We try to put out a quality reissue as opposed to just slapping another one against the wall. It goes further. I respect what we've done. I respect our legacy that we've left behind. People still have reverence for us. Oddly enough, we're still somewhat relevant because of new bands that have grown up with their dads' record collections, I suppose. I don't know. But it seems like there's still a want and people still like the music. As long as that's out there, you just want to be involved in what gets done with it a little bit so you're not just completely whored out.

Like some artists do where they reissue the same record and you have to spend $40 on the 50th anniversary reissue — when 10 years ago, you also bought it.

STINSON: I mean, these [Replacements] reissues that have been happening in the last few years, those would be the last time those could be done, because there's no other materials to add to it. But where there is material that helps tell the story more, gives people a little more insight into what was going on — I mean, if there was a way to make a movie of all these things, people would be interested in, "Wow, how did that record get made? What was going on in Paul's head when he was doing it?"

People are interested in that stuff — and I get it. I'm interested in that. I'm interested in that with all kinds of music and art where I want to know that stuff. As long as we can keep it interesting, and not throw garbage out, then I'm cool with that. That's where our involvement is somewhat important.

It is weird because you have to preserve a legacy. You made that art. You want to make sure it's presented.

STINSON: You can own it and be involved in helping to curate what they're doing in a way that's not decreasing its value. And hopefully do something cool that people are interested in. People have been buying enough of the reissue stuff that they're interested in what they're getting and what we're doing with them. Bob Mehr set that up in a way that he's been pretty useful and cool and kind of helping us preserve the real legacy and do that kind of thing.

Wronger is out now on Cobraside.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!