My favorite moment of the documentary Family Jams – which follows Devendra Banhart, Joanna Newsom, and Vetiver on their summer 2004 American tour – comes at an Amoeba Records meet-and-greet. While signing autographs and chatting with his growing legion of fans, Banhart meets Linda Perhacs, whose obscure 1970 album Parallelograms was beloved among the early 21st century Cali-folk cognoscenti over which Banhart had quickly assumed some kind of weird leadership. As he greeted Perhacs across the table, Banhart bashfully apologizes for the fact that he wasn’t wearing a shirt. “It’s okay, I’ve got mine on,” Perhacs replies with a laugh.

That moment sums up so much of who Banhart was and is. He and Perhacs were clearly vibrating on the same musical frequencies, but where Perhacs’ lone LP had quietly slipped into the cult-folk astral plane decades before its 2003 reissue, Banhart was actively striving for his own version of rock stardom from the jump. Between his rail-thin frame, denim bell-bottoms, bushy beard, mop of ropy black hair, penchant to end club shows with on-stage hootenannies, and the etymology of Family Jams, Banhart felt like a charismatic cult leader moonlighting as a folk singer, or an actor playing someone doing that.

But then there’s the music. A couple years earlier, Michael Gira heard a weird timelessness in Banhart’s demos: “These songs could have been sitting in someone's attic, left there since the 1930s,” Gira wrote in the press materials for the three albums Banhart released on Gira’s Young God label between 2003 and 2004: Oh Me Oh My, Rejoicing In The Hands, and Nino Rojo. Gira’s casting of Banhart as a one-man Smithsonian Folkways compilation was apt: Banhart was fluent in US and UK folk traditions, wrote songs that sounded like they were being cranked out of a 1920s Victrola, and sung them in a quavering vibrato that variously summoned minstrel singer Emmett Miller, pre-glam Marc Bolan, and the mid-Atlantic warble of Katharine Hepburn.

Around the same time that Banhart met Joanna Newsom and Vetiver's Andy Cabic gigging around San Francisco, he also became friends with LA-based journalist Jay Babcock, who'd recently co-founded a magazine called Arthur, which had been among the earliest outlets to profile Banhart, calling him a "freaked folknik" on the cover of its second issue in early 2003. Banhart started sending him intricately designed mix CDs of the old and new music he was listening to, and Babcock suggested Banhart make one to release on the Arthur-affiliated Bastet label.

Banhart titled the resulting 20-track compilation Golden Apples Of The Sun, after the final line from a William Butler Yeats poem that 60s folkie Judy Collins had previously borrowed. He drew its elaborate artwork, and Babcock released it to coincide with Arthur’s May 2004 issue as the first Bastet release. Officially, it dropped 20 years ago this Monday, on April Fool's Day 2004.

An excellent collection of early-aughts indie psychedelia, Apples has potent strains of New Age folk, exploratory Pagan/Wyrd psych, throwback Appalachian folk, and a bit of New York’s lo-fi “anti-folk” scene. Occasionally the pungent aroma of a hippie commune wafts through, as does a hyper-expressive, nearly childlike vocal style shared by contributors Banhart, Newsom, Josephine Foster, CocoRosie and Scout Niblett. Apart from Banhart, Newsom, and Mazzy Star’s Hope Sandoval, who guests on Vetiver’s opening track, Sub Pop signee Iron & Wine was the biggest name on Apples, two years after Sam Beam debuted the project on a different magazine’s CD compilation: Mike McGonigal’s beloved Yeti.

What’s not on Apples, nor in the interviews with Banhart or Newsom that ran in that month’s issue of Arthur, is the phrase “freak folk.” It did appear in Pitchfork’s review of Apples, but it wasn’t default yet: Vetiver’s 2004 debut was dubbed “freaked-out folk,” and a November 2004 Spin feature on Banhart, Newsom, Iron & Wine, and Kimya Dawson, among others, used every other option – ”neo-folk,” “antifolk,” “avant-folk,” “psych-folk” - but no “freak.” An evocative and alliterative phrase, “freak folk” had been circulating informally for decades – a Spin critic used it to describe Beck’s Mutations in 1998 – but the aftermath of Apples was the moment when a descriptive phrase solidified into a genre. The music that Banhart curated, and a lot of other music that kind of sounded like that music, suddenly got a new name. By the end of the year, Banhart himself was ambivalent about the whole thing: “If you were to ask me how I feel about any of the term freak folk, it's cool – you have to call it something – but we didn't name it,” he told the Times in December 2004.

Around that same time, a brief CMJ feature on James Jackson Toth’s group Wooden Wand And The Vanishing Voice was packaged with a bemused wink at the term’s quick oversaturation: “Please enjoy our obligatory ‘freak-folk’ article.” I asked Toth what he thought about his music being corralled like that. “I tend to resent being lumped in with a group of people who might happen to be friends, who might happen to be around the same age, and/or who might happen to have similar albums in their record collection,” Toth said. “I don’t hear a lot of commonalities beyond that. What does Vetiver have to do with Pocahaunted? What does Joanna Newsom have to do with Jackie O Motherfucker? There were as many bands in my cohort influenced by Sun Ra as there were by Comus. The best ones took a little from both!”

Toth still prefers the descriptor “free folk,” which emerged around the same time. Apples was released less than a year after the 2003 Brattleboro Free Folk Festival, which inspired critic David Keenan to revamp Greil Marcus’ coinage of “Old Weird America” (about Harry Smith’s 1952 Anthology Of American Music) as “New Weird America.” Where cult folkies like Perhacs, Vashti Bunyan, Bert Jansch, Michael Hurley, and the Incredible String Band are primary inspirations for freak folk, free folk was spiritually derived from the American Primitive Guitar style pioneered by John Fahey and his Takoma label in the 1960s. At the time, free folk was enjoying a own critic-led resurgence thanks in part to Byron Coley’s November 1994 Spin article “The Persecutions And Resurrections Of Blind Joe Death” and the 1997 CD reissue of Smith’s Anthology. Though the Brattleboro scene was far more experimental than what Banhart had curated, there were many overlaps. Brattlesboro figurehead Matt Valentine (of MV+EE) appears on Golden Apples, as do the open-tuned guitar tapestries of Jack Rose and the superconscious acid folk of Ben Chasny’s Six Organs Of Admittance.

Not that the musicians themselves much cared, but freak folk blew up because the music under its umbrella was far more marketable: Between Banhart and 22-year-old harpist/folk singer Joanna Newsom, the genre born from a compilation had two charismatic and photogenic avatars. The daughter of doctors who moonlighted as musicians (in 2018, Newsom’s second cousin, twice removed was elected governor of California), Newsom earned a scholarship to Mills College, but dropped out because her interest in weird old folk music didn’t fit with what that institution considered worthy of study. Like Banhart’s music, Newsom’s could be preternaturally precious: “I killed my dinner with karate/ Kick 'em in the face, taste the body,” she sings in “The Book Of Right-On,” from her 2004 debut The Milk-Eyed Mender. And like Banhart, who drew and lettered his own album artwork as an intricately detailed, world-building form of outsider art, Newsom asked a designer friend to embroider Mender’s cover, she later said, that “looked sort of like something a third-grader would make as a Mother's Day gift.” At once, the childlike art and lyrics defined Newsom’s public image while belying her instrumental virtuosity: she was making her instrument do far more than ethereal glissandos. In a later interview with Rolling Stone, she explained her technique: She uses her left hand for the regularly occurring bass notes, which she calls “the earth,” and her right for those ever-unresolving melodies, which she calls “heaven.” “Heaven and earth come together every 12 beats,” she explained.

Though she was lazily pigeonholed by (male) critics as a twee stargazer with a weird voice, Newsom in fact ranks among the best lyricists of her era. Before leaving Mills, she shifted to a creative writing focus, and Mender has moments of insight about the limits of language (“This Side Of The Blue”) and writers’ block (“Inflammatory Writ”) that simply don’t exist elsewhere. Yet even for a harpist exploring semiotics in her lyrics, Newsom’s vocal delivery is her defining musical trait. Like Karen Dalton as a Montessori School art teacher, Newsom bends her timbre to the needs of the music: She creaks like an antique door hinge and croaks like a tiny frog, and when she plays it straight, she sings like a young Björk. All of this – the harp, the voice, the out-of-nowhereness – overwhelmed author Dave Eggers, who took to Spin in 2004 to wonder if Newsom’s voice signaled that she was “crazy,” and hoped against hope that she was “not pretty,” because, I think, he wanted her to be famous on the merits of her work, and not the way all those other women become famous? What a freak.

Newsom, Banhart, and the Apples ilk slotted in with a lot of other critically acclaimed rock and rock-adjacent music from 2004. This was the year that Brian Wilson finally finished and released his epic twee opera SMiLE, the Friedberger siblings set sail on their indie-prog epic Blueberry Boat, a bunch of suspender-wearing Canadians banged on pots and screamed about their childhood on Funeral, Sufjan Stevens dropped Seven Swans, and Iron & Wine released his second album Our Endless Numbered Days. It was also the year of Sung Tongs, the fifth (depending on how you’re counting) album by Animal Collective, a group of Baltimore private-school kids who relocated to Brooklyn in the early 2000s, shared a practice space with fellow rhythmic noise-merchants Black Dice and Gang Gang Dance, and clerked at Other Music. Animal Collective weren’t on Apples, but Sung Tongs definitely sung from the same sheet, which made it much easier for a December Times trendpiece to add Animal Collective to the freak folk mix.

Toward the end of her Americana travelogue It Still Moves, Amanda Petrusich observes how the early aughts folk revival “devolved, as more and more diverse artists were swept up in the wave, into the catchall ‘indie-folk.’” Just a couple years after Devendra Banhart and Joanna Newsom emerged came M. Ward and Zooey Deschanel, amid a mid-2000s glut of childlike, whimsical, earnest, acoustic Starbucks-friendly music like Feist, the Decemberists, Regina Spektor, and Jose Gonzalez. The kinds of artisanal, childilke artwork that decorated Banhart and Newsom’s albums became part of the Etsy gig economy. Everyone, including tech startups, was putting a bird on it, and every TV ad had an adorkable ukulele soundtrack. If you want to locate the moment when post-Strokes independent music was gentrified, Iron & Wine covering “Such Great Heights” to hawk M&M’s is a good place to start. For a lot of people, especially those who worked for marketing agencies, this moment was the alpha and omega not just of “indie folk,” but of “indie” anything.

The mainstreaming of twee-folk signifiers – flower crowns at Coachella, Marnie’s wedding – happened while Banhart and Natalie Portman were in love with everything, and he was advising Kat Dennings on orgasm detection, and Newsom was marrying SNL comedian/musician Andy Samberg and narrating Inherent Vice. As for the rest of the artists on Apples? They’re mostly still active and likely don’t care much about what happened to “freak folk.” But while the phrase still triggers groans, it definitely had an impact. In the same way that Screaming Trees laughed at “grunge,” but the existence of grunge enabled them to sell lots of albums, whatever “freak folk” was carved a significant space for a lot of music to gain notice it wouldn’t otherwise have. In 2005, for instance, it enabled LA songwriter Alex Ebert to leave his new-wave band Ima Robot, buy a Devendra Banhart Halloween costume, and become Edward Sharpe.

Like all music genres, freak folk is both made-up and very real. No matter how dumb the phrase sounds, it exerted actual effects on a lot of musicians caught up in the heat of the discursive moment (and its anniversary commemoration 20 years later). Toth understands how the system works: “If a catchy name encourages people to rediscover and support this music in 2024, they are free to call it whatever they like.”

Also, like any music genre, the definition of freak folk is a matter of argumentation and persuasion: who’s in and who’s out, when it starts and when it ends, is based upon whatever criteria works best for you. For me, freak folk jelled in 2004 around Apples, highlighting a group of musicians who’d been playing for a few years, some of whom had connections to similar DIY/indie/CD-R-based folk scenes. Partially because it was song-based, twee, and had two musicians who posed for magazine covers as its representatives, freak folk quickly spread, before burning out in 2006 at its apex: Joanna Newsom’s Ys.

Here are 20 songs, some from Apples, others from elsewhere, that encapsulate that brief, weird moment.

The cute, seemingly possessed child on the album cover. The ukulele. The high-pitched vocal warble that sounds like it’s emanating from a wax cylinder. A hissy, lo-fi recording. Lyrics that ask, “If you were a bird how would you fly?” Decades later, one of the oldest records chosen by Banhart for Apples sounds like a test-run for the twee-ness that would dominate the second half of the decade. But that’s reverse-engineering: in the early 2000s, virtually no one sounded like Josephine Foster. Born in Colorado and immersed at a young age in the American Songbook – from Tin Pan Alley to Appalachian folk music – Foster moved to Chicago to study opera at Northwestern. Like Joanna Newsom, she dropped out of school and started releasing CD-Rs of her own music soon after. “The truth is, I wasn’t a very good opera singer,” she said in 2005, with a laugh. “I sang out of tune, I made a lot of mistakes. I was quite a big failure.” At opera? Sure.

To the best of the Secretly Canadian co-founders’ recollection, Emma Niblett, who was performing as Lion, passed Jason Molina a demo at his September 9, 2000 show in Leicester, UK. The label was enamored of Niblett’s bluesy phrasings, expressive singing, and stark production – as was Molina, and later Banhart. As businesspeople, the label was worried that a young woman singer/songwriter with a feline moniker would be deluged with Cat Power comparisons (to be fair, it’s not unimaginable that a casual listener would confuse “Wet Road” for a Moon Pix demo), and so after Niblett borrowed “Scout” from To Kill A Mockingbird, Sweet Heart Fever came out on Secretly Canadian in late 2001.

After dropping out of the San Francisco Art Institute, Banhart traveled the US and Europe, recording songs as he went – sometimes on a four-track, others by calling friends and singing into their answering machines. In 2002, he mailed a cassette of recordings – wrapped with a single marble – to the German-based Hinah Records, which released it unchanged as The Charles C. Leary. The title track – reissued on Banhart’s Young God debut Oh Me Oh My later that year – is, according to Banhart, about a ship his great-grandfather owned, and is “the most important song on the album.” There is evidence that such a steamship existed, and it apparently sailed out of Banhart’s home state of Texas, though it wrecked in the late 1870s. Regardless, “Leary” is the best early evidence of Banhart’s fact-adjacent tendency toward self-mythologizing.

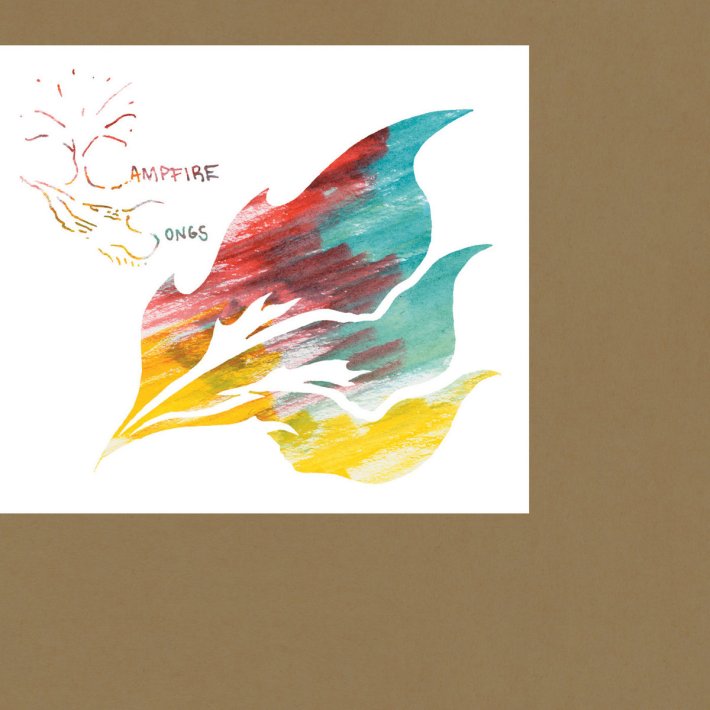

Sharing admiration for Drag City-style indie rock, the psych-folk of Syd Barrett and the Incredible String Band, and the synth-dominated score to The Shining, Animal Collective came together in the summer of 2000, jamming in Dave Portner’s Bushwick apartment and, to paraphrase Portner, trying to play acoustic guitar like they were making techno. Campfire Songs, the first cohesive example of what the quartet was capable of, was recorded to MiniDisc on a screened-in back porch in rural Maryland in 2001, attempting to capture what Josh Dibb calls a “sonic invocation of a campfire with this ever-shifting, gaseous sound.” The resulting album is a lightly overdubbed single take of the entire 40+ minute performance, and “Doggy” – a pretty, strummy folk tune about a dead puppy – is the album’s macabre highlight.

“I just know that this tour is going to be considered the magical tour of 2004,” said a rapturous Anohni in the Family Jams documentary, preceding her one-off performance at the Bowery Ballroom stop of the 2004 jaunt. “It’s a significant moment for culture. I just feel like, ‘gimme that coattail!’” she concluded with a laugh. Of course, Anohni needed no help. After more than a decade of composing and performing, following a formative decade in the Bay Area, her career took off in 2005, cosigned by admirers Banhart, Lou Reed, Boy George, and Rufus Wainwright. Banhart closed Apples with Anohni’s take on Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Lake,” a fitting conclusion for a compilation named after another poem exploring the dark mysteries of the natural world.

In 2003, Joanna Newsom was playing keyboards in the Pleased, a Strokes-y rock band led by her former Mills College classmate Noah Georgeson, while recording intricate and verbose folk music on CD-Rs. At some point that year, one of her friends slipped Will Oldham two EPs titled Walnut Whales and Yarn And Glue, which Oldham passed to Drag CIty. A year later, Newsom’s verbose ode to childhood daydreaming and Narnia speak “Bridges And Balloons” opened The Milk-Eyed Mender and served as Apples’ second track. Though Mender is no doubt a one-woman show, with Newsom’s vocals and Lyon & Healy harp front and center, Georgeson’s production is key. The constant overtones spun off of the harp’s strings make post-production tweaks tougher than most instruments, and though Georgeson was learning as he went, the two created a crisp, resonant sound that rightfully directed all attention at Newsom’s voice and instrument. Indeed, Newsom could rightfully be credited for introducing most people to the notion that harps indeed produce resonant – “earthy,” in Newsom’s phrasing – bass notes.

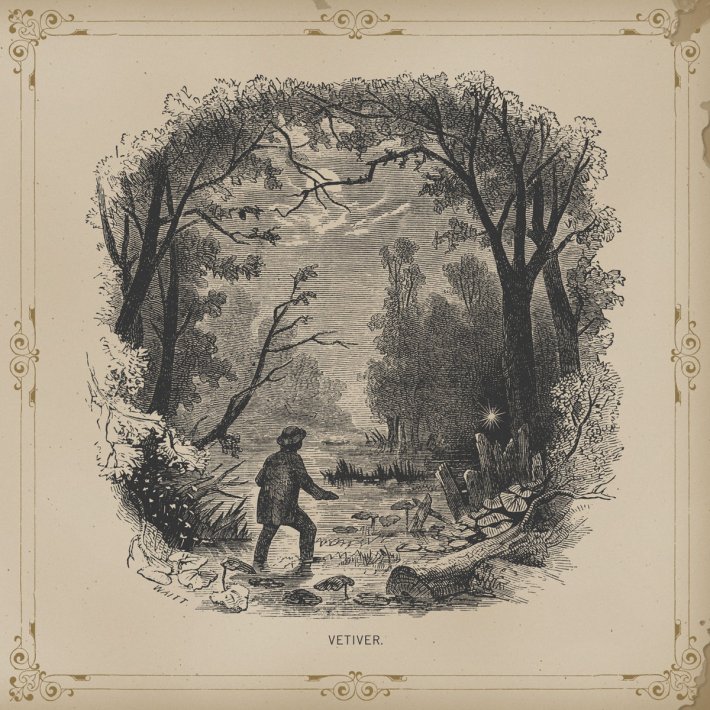

Up until the age of 25, Andy Cabic had only played electric guitar, most notably in the mid-'90s alt-rock band the Raymond Brake. But when his primary instrument was destroyed in a car accident, he was given a cheap acoustic as a gift, and taught himself to fingerpick. He relocated to San Francisco, hooked up with Banhart, and started Vetiver as a collaboration between the two, but the group soon expanded to incorporate cellist Alissa Anderson, violinist Jim Gaylord, and guest appearances on the band’s 2004 debut from Newsom, Hope Sandoval, and on the epic album closer “On A Nerve,” former My Bloody Valentine drummer Colm Ó Cíosóig (who’d previously played with Sandoval as Warm Inventions). Though Banhart chose “Angels’ Share” to open Apples, “Nerve” is the best display of Cabic’s ambition, both signaling where freak-folk adjacent bands like Grizzly Bear would soon go, and predicting Vetiver’s pivot to crystalline country-rock with 2006’s To Find Me Gone.

Devendra Banhart - "Rejoicing In The Hands" (Feat. Vashti Bunyan) (2004)

Like Banhart and Newsom and Foster a couple decades later, Vashti Bunyan dropped out of art school. In the mid-1960s, she entered into the burgeoning London music scene. She released a single in 1965 – the Jagger/Richards original “Some Things Just Stick In Your Mind,” with Jimmy Page on guitar – but her career stalled out. In 1968, she hooked up with a bohemian art-school friend, bought a horse-drawn wagon, and set out on a 700-mile wayward trek to Scotland, where Donovan had promised he was setting up an artist’s colony. Along the way, Bunyan wrote an album’s worth of songs, which was released in late 1970 as Just Another Diamond Day. Despite an all-star cast of UK folk – produced by Joe Boyd, featuring members of Fairport Convention and the Incredible String Band – the album sold poorly, and Bunyan left the music industry to raise a family. Meanwhile, her cult steadily grew, and when the album was reissued in 2000, Bunyan found herself with a lot of new fans, including Stephen Malkmus, who booked her for a 2003 festival appearance, and Banhart, who got Bunyan to duet with him on Rejoicing’s title track. Bunyan benefitted greatly from freak folk: two years later, she recorded an EP with Animal Collective, released her second album, and licensed “Diamond Day” to T-Mobile.

About a decade and a half before Brattleboro, a New York folksinger called Lach was turned down for a gig in Greenwich Village’s legendary club Folk City. A combination of spite and entrepreneurial spirit led him to open a club called The Fort and launch the New York Antifolk Festival. Unlike freak folk, antifolk became a bonafide scene, providing a space for acerbic, experimental, and theatrically inclined musicians to ply their trade, helping to launch the careers of Regina Spektor, Kimya Dawson, and Nellie McKay. In 2000, Diane Cluck, a local poet who’d trained at the Pennsylvania Academy Of Music, stopped into antifolk haven the Sidewalk Cafe and found her people. After a few years of gigging and cutting CD-R’s – Banhart added a track from 2001’s macy's day bird to Apples – Cluck decamped to an art colony in southern California to write new material, which became her best album, Oh Vanille/Ova Nil. “Easy To Be Around” is an incantatory devotional to finding peace with another person, though Cluck’s delivery is anything but relaxed.

Shorn of context, the music made by Espers starting in 2003 could more easily than any other artist on this list be confused for a lost album from the fertile late UK folk/rock scene that spawned baroque, tradition-centric bands like Pentangle and Fairport Convention. Espers’ core of Greg Weeks, Brooke Sietinsons, and Meg Baird came together in the Philadelphia DIY scene of the early 2000s, filtering its trad-folk influences through a groovy American psych-rock filter. Banhart selected “Byss & Abyss” for Apples, and it’s the perfect evocation of the Espers sound: Weeks and Baird placidly harmonize over strummed acoustic guitars and Meg’s sister Laura on flute, and about halfway through, Philly indie-rock veteran Quentin Stoltzfus fires up the tone generator, sending the song spiraling back into the outer orbit of space-age analog experimentation. While Espers has been dormant since 2009, Meg Baird’s subsequent Drag City work is even better.

The project of Oakland-based singer/songwriter Dawn McCarthy and collaborator Nils Frykdahl, Faun Fables highlights the overtly theatrical and prog-rock undertones of freak folk. McCarthy’s powerhouse vocals are a little Sandy Denny and a little Grace Slick, and her training in stagecraft and live theatre ensures that no opportunity to dramatically expand her music into the fantasy realm is left ungrasped. 2004’s Family Album was Faun Fables’ breakthrough, and album opener “Eyes Of A Bird” is still its best song. It starts off with a chance meeting (“You're like me/ You know the occult/ It's what I learned from my mom, and other adults/ Let's make a star here on the pavement...”) and follows the path of the two likeminded souls as they embark on a lifelong quest. The narrative isn’t as important as the song’s gradual build toward a torrential crescendo, as if their shared spiritual journey loosed some latent, possibly contemptible force from the belly of the universe.

The “Tomorrow Never Knows” of freak folk, “Leaf House” was instantly the most accessible work that Animal Collective had released. A massive step beyond anything on Campfire Songs, it was the kind of song-as-portal with which you could blow the mind of a psych-curious normie friend only familiar with Revolver or late-'60s Beach Boys. Looped acoustic guitars, intricately hocketed vocals, all kinds of fantasy-land animal references (if any album apart from the original could be called Pet Sounds, it’s this one), Sung Tongs was recorded by Noah Lennox and Dave Portner in Portner’s family home in Colorado, raising the group’s production values significantly. To journalists, the album solidified the group as “freak folk” (to the band’s vocal disdain), but more importantly, it coronated them as the most compelling experimental rock musicians of the moment.

There was surely an undercurrent of sexism in the barrage of insults hurled at the Casady sisters between 2004 and 2006 – plenty of dude groups were committing similarly weird acts of childlike whimsy and hipster appropriation with a fraction of the critical animus thrown at their imaginative, out-of-nowhere debut 2004’s La Maison De Ma Reve. Recorded, as legend has it, in a bathtub in the Parisian apartment shared by Bianca (a model) and Sierra (a trained opera singer), Maison was intended, the sisters assert, to be passed as a CD-R between friends before Touch & Go convinced them to release it. Banhart was predictably impressed with the Casadys’ ability to blend ancient-sounding blues with whimsy, and chose “Good Friday” as the penultimate Apples cut. But CocoRosie and Banhart shared a deeper connection: A decade or so before the public discourse on cultural appropriation reached its long-overdue tipping point, and the same year that Banhart wisely lopped the last four words from his original album title Rejoicing In The Hands Of The Golden Negress, Sierra and Bianca adopted Billie Holliday-style sonic blackface and sung the n-word like it was a natural part of their vernacular on “Jesus Loves Me.” The duo come by their poor choices legitimately – their mother’s partner has a bad history of appropriation herself – but, as with Banhart, they demonstrate that freak folk’s fixation with Old Weird America occasionally regenerates that era’s most intolerable aspects.

Devendra Banhart is never shy about promoting his friends, but his appreciation for guitarist Ben Chasny is something different. “Ben Chasny’s the garden, and I’m the snail,” Banhart once crowed in an interview. Chasny had been releasing experimental guitar music as Six Organs Of Admittance for several years when Banhart borrowed the unreleased “Hazy SF” for Apples (in the compilation’s liner notes, the song appears “courtesy of Devendra Made Me Do It Records”), though the track’s Vetiver-esque folk-rock sounds little like Chasny’s typical work. Initially inspired toward guitar by Leo Kottke and John Fahey records, Chasny embarked in the mid-1990s on a wide-ranging, self-taught, immersive approach to guitar. In a single Arthur interview, Chasny talks about the Buddhist origins of his performance name, his hexadic system of playing and improvising (he’s got his own card deck), and drawing inspiration from Anthony Braxton, Nick Drake, Gaston Bachelard, and Marcel Mauss’ The Gift. The year after Apples, Chasny released School Of The Flower, his first album recorded in an actual studio, and the increased production quality on tracks like “Saint Cloud” deeply enriched the experience of his delicate fingerpicking and chanting over a bed of murky, shape-shifting drones.

"When I was in high school I really thought I was going to be a political journalist," Jana Hunter explained. “But then I ended up not going to college, and found myself in my early twenties really only knowing how to do one thing – make music.” Hunter grew up in Texas and didn’t think of himself as a musician, as much as a person who quickly recorded the musical ideas that frequently came into his head. He put out a couple CD-Rs and recorded a split LP with Banhart, and then Blank Unstaring Heirs Of Doom, culled from a decade’s worth of material, became the first album released by Gnomonsong, the label that Banhart and Cabic started in 2005. Like the skilled A&R executive he knew himself to be, Banhart selected Hunter’s lonesome, guitar-and-violin country tune “Farm, Ca.” for Apples, easily the most traditionally structured song to emerge from Hunter’s prolific, ever-wandering mind at that early point in his career.

A year or so after coming together in Williamsburg at the same time as Animal Collective was jamming in Bushwick, Akron/Family signed to Young God. As they recorded their 2005 debut, they served as Gira’s house band, backing him on his Angels Of Light project. Both albums came out within months of one another, with Akron/Family dialing back the group’s hairier, free-jazz-influenced jamming instincts (if you saw them play live during their eight-year existence, you saw them at their best) for a more slimmed-down presentation. “Running, Returning” is the highlight, building a hootenanny-style tune with lyrics that should sound familiar by now (“come walk with me in the morning light”) on top of an elemental drum-circle rhythm.

Riding high on critical goodwill after his huge 2004, Banhart decamped to XL, and with Cripple Crow tried his best to turn freak folk’s family jams into a bonafide scene. The Sgt. Pepper’s-mimicking album cover features Newsom, Georgeson, Cabic, CocoRosie (Banhart was dating Bianca at the time) and Espers, among others, suggesting a year later that Apples was mostly a mixtape of Banhart and his friends, but which to Pitchfork represented “the loose-knit scene's strongest group effort to date.” Seventy-four minutes of jammy, jazzy psych-pop with the Beatles’ ‘67-’68 era dominating its moodboard – there’s a song called “The Beatles” that sounds like a White Album castoff – Cripple Crow showed that Banhart could upgrade his productions without losing the vibe of a Northern Cali ashram jam. Some of his most accomplished compositions are here: “I Feel Just Like A Child” sounds like 1972 Paul Simon, and the anti-war ditty “Heard Somebody Say” could’ve been a Norah Jones composition (a compliment). Speaking of Ms. Jones, one of the faces of Starbucks’ mp3-era move into midbrow music retail, Banhart was so determined (playfully, I suspect) to keep his music away from $5 espresso buyers’ ears that he tacked a song onto Cripple Crow that satirically endorsed pedophilia. An unexpectedly punk move from pop’s most fashionable hippie.

In 2003, Alabama-born musician and Arthur contributor Nathan Shineywater created the Quiet Quiet festival, hosted in the northern California cities of Bolinas and Big Sur and featuring appearances from Banhart, Newsom, Six Organs Of Admittance, and numerous other gentle psychedelic souls. At the same time, along with Fender Rhodes player Rachel Hughes (as “Nabob” and “Rabob”), Shineywater was proving that Brightblack Morning Light was the rare group of starry-eyed hippies who could do justice to American R&B. Produced by Cripple Crow’s Tom Monahan, Brightblack’s self-titled album (released by Matador) sounds at times like a Muscle Shoals-era soul 45 played at 33⅓ speed, and for the last few minutes of “Star Blanket River Child,” like a runout groove repeat of a simmering ‘70s cop movie theme. Though, for some, Brightblack’s trademark drowsy soul-haze and embellished backstory (living in a chicken coop on a commune) could distract from the band’s righteous environmental politics – their first gig was a benefit for the Green Party of Alabama and they were active in numerous conservation efforts - Arthur publisher Jay Babcock sees it the other way. “That blissfully stoned, beautifully mellow, deeply soulful sound involves nature, sympathy, cosmic awe,” he mused, adding that the duo were “more deeply rooted to the planet than any musician(s) I know.”

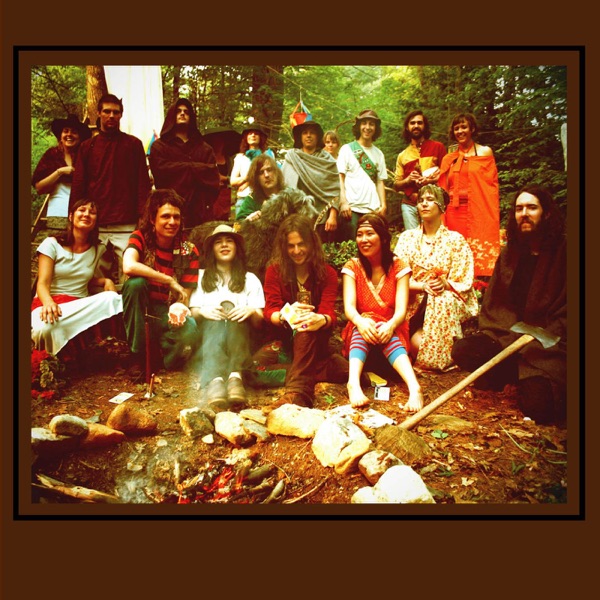

I distinctly remember talking to a young band in 2009 who were set to sign to a big indie label, but had to change their name, because Feathers, perhaps predictably, was already claimed. Like Brightblack Morning Light’s overt hippie-cult finery, a single glance at Feathers might suggest you’re gazing upon an industry plant ginned up to satiate overeager mp3 bloggers. A Cripple Crow-esque cover photo of a bunch of groovy longhairs sitting around a campfire? Check. Signed to Gnomonsong? Check. A band name and track titled “Old Black Hat With A Dandelion Flower” that seem to have emerged from a Target Women’s Apparel buyer using a freak-folk name generator? Check. Marketing savvy notwithstanding, Feathers were no joke: Hailing from the same New England territory that spawned the proto-free-folk Tower Recordings collective, the band is a gnarlier, dronier version of onetime tourmates Espers, and “Ibex Horn” is the unnerving centerpiece of their dark ceremony.

The most freakishly anticipated album of 2006 – such that it leaked from Pitchfork’s hacked mp3 server two months before its release date – Ys still managed to exceed the expectations set by The Milk-Eyed Mender. Benjamin Vierling’s old master-style Newsom portrait/album cover – with details and symbols to keep message board obsessives speculating – sets the tone for an album on which every atom feels like the product of sustained obsession. Working with a 32-piece orchestra playing arrangements by Van Dyke Parks – whose Beach Boys collaborations and solo work situate him near the roots of freak folk’s family tree – Newsom crafted a lavish, LARP-ish concept album, her impossibly detailed and florid lyrics operating at an extraterrestrial scope that suggests Dark Side Of The Moon, Songs In The Key Of Life, or Alice Coltrane’s Universal Consciousness with a detour through modernist poetry. Take the most memorable refrain from the 12-minute, constantly shape-shifting “Emily” that opens the album: “The meteorite is the source of light, and the meteor’s just what we see/ And the meteoroid is a stone that’s devoid/ Of the fire that propelled it to thee.” It’s a deceptively devastating explanation of the odd and unquestioned connections between words, experiences, and truth: meteoritics for poets. If Banhart was freak folk’s gregarious circus ringleader, Newsom was its brain and heart. And if music genres boil down to arguments and the drawing of lines, freak folk’s brief moment in the sun concludes with its magnum opus.