We've Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

In the greater pop pantheon, Def Leppard may not get enough credit for their hi-tech studio innovation, mind-blowingly polished live shows, and ego-free levels of ambition. If you're a Def Leppard die-hard, I'm not telling you anything you don't already know. And yet it bears repeating. Formed in 1976 in Sheffield, Def Leppard started out as a group of teenagers, each of whom had rotating interests in heavy metal, hard rock, glam, pop, and arena rock. After a few lineup changes, Def Leppard's debut self-titled EP, dropped independently in 1979, sounded like a messy but promising mix of Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, and AC/DC — a swirl they emulated on their 1980 studio debut, On Through The Night.

On their follow-up High 'n' Dry (1981), you can begin to hear echoes of Queen, with massive, dramatic guitar licks and soaring vocal harmonies, courtesy of AC/DC's favored producer, Mutt Lange. The superproducer came back on board for Def Leppard's third album, 1983's Pyromania, which crystalized the group's bombastic ascent to pop metal — not to be confused with glam metal's more sinful progenitors, Mötley Crüe and Poison. Raining down hooks on singles such as "Photograph," "Rock! Rock! (Till You Drop)," "Foolin'," and "Rock Of Ages," Pyromania was not only a triumphant pop album — it introduced a new way to record rock music, period, by having the band record to a drum machine's click track (actual drums were recorded last), letting Lange and Def Leppard play around with arrangements. It might sound silly for a guitar-based band to eschew use of drum machines now, but in the early '80s? Electronics and analog simply did not mix.

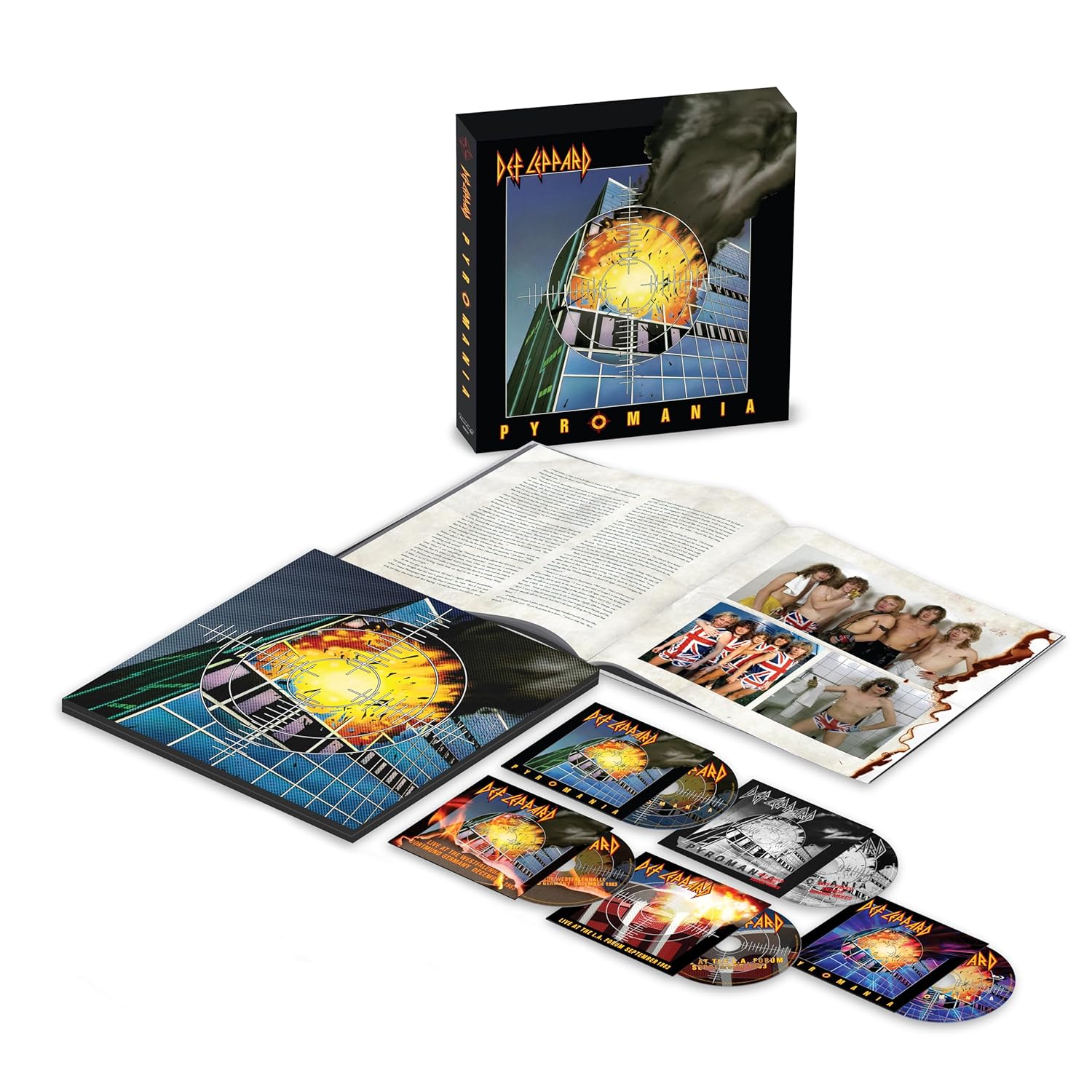

Last year, Pyromania turned 40. In a few weeks, the band will reissue the album on two LPs; in a few months, they'll hit the road on a co-headlining tour with Journey. Ahead of Def Leppard's forthcoming reissue release and US tour, Stereogum talked with lead singer Joe Elliott, bassist Rick "Sav" Savage, and co-lead guitarist Phil Collen (who joined mid-Pyromania recording, replacing founding member Pete Willis) about four decades of Pyromania, sharing a stage with Taylor Swift, and why they never, ever, ever sing to backing tracks.

40th Anniversary Deluxe Edition Of Pyromania (2024)

https://youtube.com/watch?v=3qq1I8QRhYo /wp:paragraph -->

https://youtube.com/watch?v=Hu3ckr-Lr00 /wp:paragraph -->

https://youtube.com/watch?v=3qq1I8QRhYo /wp:paragraph -->

I heard something about Cybernauts planning to finish an album — one Joe first mentioned in 2012. Is that still happening?

COLLEN: We are going to finish the album. We've got some other songs that we're going to [record]... They're all Bowie-era, so "John, I'm Only Dancing." We spoke to Woody Woodmansey, he was the only remaining member of the Spiders From Mars.

Mick Ronson, who was David Bowie's guitar player, passed away in the early '90s, and we'd done a benefit concert, Hammersmith Odeon in London, and we got to play with Woody Woodmansey, Trevor Bolder, who were the original Spiders From Mars with Mick Ronson, and it turned into something. I said, "Wow, wouldn't it be great if you'd done a gig?" So we did another thing up in Hull. They did a recognized benefit for Mick Ronson. Then we got into doing a tour. We actually toured England and done some Irish shows, and then we was up in Japan.

We recorded a whole live thing, and it was so much fun. Me and Joe were obviously huge, huge, huge Bowie fans. It was a 'pinch me' moment. We are playing these songs with our heroes, and I listened to Aladdin Sane, Hunky Dory, and Ziggy Stardust all the time still, they're my three favorite Bowie albums.

Performing On CMT Crossroads With Taylor Swift (2008)

Taylor Swift is on the record as being a huge Def Leppard fan. How was it to perform with her on CMT Crossroads?

COLLEN: What was lovely about it is that she'd gotten into [our] music because her mom and dad played Def Leppard all around [the house], and Shania Twain, so obviously the Mutt Lange factor is in there.

But her songs, they fit in very easily to what we were doing — like the chord structures and the sounds of it, it was so easy to adjust into it and play along with her and her band. It was like, wow, this really works. We had a blast. And she was great, and obviously [she's] the biggest star in the world right now. It is crazy.

[She's] very ambitious and determined, and I love that. Because I got that kind of vibe myself. I really applaud her for doing that. She works so hard. You can't say enough about it.

SAV: It was fantastic. We spent a week together. It was a great experience. Her band were fantastic, as was Taylor. I mean, people realize what a superstar she is now, and she was pretty big then. For somebody of such tender years to have written so many songs by the time she was 18, it was incredible.

I suppose at the time she was a fan [of ours]. But she grew up without any choice because it was her mother that was the big fan. She was almost pummeled to death with Def Leppard from, well, probably from in the womb, as it were. But yes, she couldn't escape us. I guess eventually it was either go mad or like us, and I think she chose to like us.

It was great to play some of her songs, but also some of our songs with her singing along with Joe, it puts a different slant on everything. You understand that some of the songs you've written can translate in different formats. That's what made it fun more than anything else — bringing a little bit of Def Leppard into her songs, which would've been cool for her and her band too.

I assume you've been approached by a lot of artists over the years telling you what big fans they are of Def Leppard. Have any surprised you?

SAV: Yeah, throughout the years there's actually been more than we care to appreciate, really. A lot of the bands that, certainly in the noughties, would come to us and say we were really inspirational when they were getting together, that our early albums inspired them. I can't even remember most of them to be perfectly honest, but they were all a little hardcore. They were that noughties nu-metal that was more extreme than we've ever been. It was like, "Whoa."

Guys would come up to us and they'd be almost gothic and a little bit frightening, and you think, "Oh, Christ, they're going to have a right go at us here, they're going to call us pansies and wimps and that type of thing. They're going to think that we're in bed with bands like Journey and R.E.O." It's actually quite the opposite. It's like, "Dude, High 'n' Dry, that made me want to pick up a guitar."

It's actually quite flattering in a sense that even our early stuff influenced a whole range of people from the nu-metal guys to artists like Avril Lavigne. When she was starting, she would say, "Yeah, I would listen to your records." It's a real compliment. You just don't know what you're doing when you're creating records. You don't know the effect that they're going to have on people 20, 30 years later.

That's hysterical about the nu-metal groups.

SAV: Yeah, Disturbed and bands like that. It was just like, really?

This is hot off the press, but we have just mastered a one-off single, and playing on it is Tom Morello from Rage Against The Machine, who was a huge fan back in the day when he was growing up. High 'n' Dry was like his Bible. He's playing a solo on our new single, it's going to be out there pretty soon. That's just another example — you keep passing the baton around, and it's fantastic.

Developing A Def Leppard Animated Series (2009)

Is it true that, at one point, Def Leppard had agreed to be the subjects of a (now-shelved) animated series?

SAV: You know what, I'd completely forgotten about that, but I think you're right. Now you've just turned a cog in my memory.

This didn't come from the band — this came from outside as an idea. But yes, there absolutely was an idea floating around to create five characters that were us, and it was Def Leppard, but in cartoon form. How they were going to save the universe through doing dastardly deeds or whatever it was.

It never really saw the light of day. You do get a lot of things thrown at you, just different ideas from outsiders saying, what about this? What about that? Some of them you go, I don't really care, but let's take it to the nth degree and if we like it, we'll run with it. But for whatever reason it never really took off the ground, that cartoon thing.

Finally Streaming Their Classic Albums (2018)

It famously took Def Leppard a long time to get their most classic albums onto streaming platforms. Now, with your label UMG pulling out of TikTok, do you have any feelings about your music not being accessible to fans on that platform?

ELLIOTT: Well, the history of this is, you have to think of Universal Records as an umbrella. That umbrella, say it's one of those that you can borrow from the lobby of a hotel. Many different people have been under that umbrella. In 2008, when we first negotiated with Universal to go digital, the deal was reneged on by the then-regime. Then, of course, we threw the toys out of the pram, and we said, "Well, okay, fine, we'll go our own way. We'll rerecord like Taylor [Swift]'s doing." We did that for a while, and they kept coming back to the table, and we kept saying no. Eventually, the offers kept getting better and closer to what the original offer was. Howard Kaufman, our manager at the time, said, "This is as good a deal as you're going to get. I think we should go with it."

By then, the people under the umbrella of Universal were on our side. These were good people that used to maybe work lower down in the trenches in the past that are now in charge. They're like, "We love you guys, come back." I think we announced the deal January 2018, and within three years we were over four billion streams, and we're over six now, pushing seven even, I think. It's been an amazing journey for us to play catch-up and finally be in the big numbers. As regards TikTok, as far as I'm aware, every artist on Universal can no longer be found on TikTok-

Correct.

ELLIOTT: ... Because they're going through some, what sounds to me like, heavy negotiations. My theory is it's temporary. I'm sure it'll all come back. We survived not being digital until 2018, and we still had an audience out there because, with social media, if you can't get our music, people were either trading it or they already owned it because they'd bought the vinyl. Then they bought the cassette, then they bought the CD, and they were still playing their CDs. Now, of course, we're on every Spotify, Apple, whatever server you want to use.

As for the TikTok thing, I don't know what the answer is. I'm not in that negotiation, but if Taylor's not there and U2 are not there and all the other artists on Universal like ourselves, I'm sure they'll be back soon enough. I think it's like everything else. I think if you go to the supermarket for a tin of beans and you get to the shelf and it's empty and you go, "Ah, damn it," you go, "Oh, well, okay, so I'll buy hula hoops." You just get on with it until it comes back. You just find a way around it. You know what I mean?

Most people have probably got our music downloaded, so if they're that desperate to hear us, they don't need to go to TikTok for it. They can go to our website and look. They'll find another route to listen to us if they're that desperate to hear us, and if they are, I'm grateful that they care enough to keep looking. Who knows? Like everything else, something's really hot and then 10 years later people can't remember the name of it, like Napster. It doesn't mean anything anymore, and it was such a big deal when Lars [Ulrich] took them to court and all that kind of stuff. Maybe TikTok fades away anyway and something else comes along. I don't know.

At the end of the day, it's all down to the money. If you're going to watch an artist 10 trillion times on a certain thing, artists still deserve to be paid. So, I get it. But it's out of my wheelhouse to come up with a solution that suits every party, because at the end of the day I'm just the guy that tries to rhyme "maybe" with "baby" and see if I can get away with it.

Pyromania (Deluxe 40th Anniversary Edition is out 4/26.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

https://youtube.com/watch?v=D4dHr8evt6k /wp:paragraph -->

https://youtube.com/watch?v=Hu3ckr-Lr00 /wp:paragraph -->

We don't use backing tracks. We use effects. God, who wouldn't? When there's four people singing, we use effects. There's no tapes of backing vocals. We use keyboards. We use a few drum loops because, in fairness, two-armed drummers use drum loops, but Rick Allen, to play a song like "Rocket," it's a cacophony of toms that one arm couldn't play. So, yeah, we use a triggered loop, which is part of his drum kit, but [U2 drummer] Larry Mullen's been doing that for years. So have thousands of other drummers to enhance a sound. But backing tracks or playing along to a backing track — we've never done that, never. We've never mimed to the vocals, or we've never had multiples of stuff on tape. It's literally live.

If we're running at about 90%, it's more than most people's 100%. Because we do play and sing, it does take a toll. You can, say, play Denver, where it's a mile above sea level, and if you've got a gig the next day, your voice is going to be pretty shot. We have to get to a level where if it's a little under last night, it's still acceptable to the audience because of the adrenaline and the fact that it is live and you can hear maybe a bit of hoarseness or somebody's fingers slip because it's so cold, they can't keep their fingers on the strings. Things like that happens to every single band, and that's what brings the humanity to it. But we're very proud of the fact that we play live, and we sing live, and we don't use tapes.

So, sorry Chuck and Chris Holmes, but you've got that one completely wrong. But thanks for thinking that we need them. We don't. We're that good.

I'm not a musician, but I'm married to one. If you had been using a backing track, I'm sure my husband would've said something to me.

ELLIOTT: That's the thing about backing tracks, is that they never change. You'd only have to go on YouTube and see, say, one performance of the track from us on the last tour and then watch one from two nights later or something. There'll be slightly different phrasing, or one of them would be a better singing performance than the other, something like that. Like I said, the only things that we use is effects, like the beginning bit of "Love Bites," there's a keyboard section. We use that as a trigger loop. The "Rocket" drums are enhanced by loops. [Rick] Sav plays a lot of keyboards with his feet so that any keyboard sounds that you hear, he's got bass pedals like Geddy Lee uses in Rush to enhance their sound. You'll often see Sav... He looks like he's stamping on cockroaches. He's actually moving from the E to the A with foot pedals underneath and playing the bass and singing at the same time. Like I said, we practice so it becomes muscle memory. It's something that we strive to achieve, and we're very proud of the fact that we pull it off. Like I said, it's a left-handed compliment when people go, "That's not live." If you work hard enough, you can pull this stuff off. It is doable.

Pyromania represents a historic sonic shift for the band. Keeping in mind that you'd worked with Mutt Lange on 1981's High 'n' Dry, how did that Pyromania’s poppier presentation take shape?

ELLIOTT: Essentially the way I remember it is that when we did High 'n' Dry in '81, the studio we did it in was Battery Studios. The mixing desk, the recording equipment, the outboard gear was identical to what Mutt had used for Highway To Hell in 1979, never mind 1980's Back In Black, which was mostly done, I think, in Nassau. But they came back to London to mix it and do a few overdubs. But we'd done High 'n' Dry in that studio. We'd been in it for about three months to do High 'n' Dry. Having been on the road for a year or nine months as it was for the High 'n' Dry album on and off, you forget what the studio looks like after a while. Then you get back in there in 1982, and you go, "Oh, wow, I don't remember it looking like this."

Suddenly there's an SSL desk in there and there's new equipment coming in and new outboard gear that can do stuff that saves time. If you want the backward echo effect on something, you just have to take the tapes off, turn them backwards, record it backwards, and then flip it back again. Now, suddenly, there's a little machine that says "reverse" on a button and you push it. It saves all that messing around. Things like that would start out in the '80s. I don't remember specifically which of these little tricks and bits of equipment were on offer to us in 1982, but I do remember that it was moving that way.

By the time we got to work on Hysteria in '84, '85, it had moved on even further. But in that one year from '81 to '82, it had moved on a little bit. There was also a plethora of huge hit singles in the UK that were drum machine-based: New Order, the Human League, and all this kind of stuff... And you've got to remember, we haven't seen Mutt for the best part of nine, ten months. When you first get together, there's a lot of coffee and, "Hey, how's it been? What have you been up to, then? You guys have been out on the road." "What have you been doing, Mutt?" "Well, I've been producing this band and that band and blah, blah, blah." Then conversation drifts around to, "Well, okay, so where are we with this stuff?" We'd done a month's pre-production with Mutt in a rehearsal room where all we had was a little cassette recording the arrangements of the songs. We didn't mic anything up. We didn't try and record anything properly. We were just recording the songs.

In fact, when we went into Battery Studios in '82, we hadn't got barely one lyric written. We'd arranged all the songs with lyrics in mind. In other words, they were set up. You got your eight bars for a verse, and you got your four bars for a bridge, and we're la-la-ing melodies, but we didn't have anything specific written because we were going to do it on a song-by-song basis once the backing tracks were recorded. I was fine with that, and so was Mutt. But Mutt probably was responsible for saying... There's a generic term we've used. It's like, "Do you want to make High 'n' Dry 2, or do you want to make an album that nobody else has ever made?" [In terms of drum machines], you can go back further than New Order and the Human League. They were influenced by the likes of Kraftwerk, who were using in drum machine technology in 1975, but they brought it into a pop field. The Pet Shop Boys were doing it. What wasn't happening, there was no rock bands bringing in this new technology.

We were all very excited at the thought of doing this and amalgamating it into our sound. We still had drums, we still had cymbals, we still had the big sound… In 1982, we were listening to tapes coming in from America of what was in the charts, and it was Asia, REO Speedwagon, and Styx. They were pretty much just recording the same way as they always had. What we were trying to do was avoid that — not ostracize it. We were trying to enhance it and move it along a little bit. Because we still needed to appeal to the rock fans without alienating them too much. I would imagine there wouldn't have been that many Def Leppard fans buying New Order albums and vice versa, but there's no reason why it can't leak in a good way.

You were thinking about the new technology.

ELLIOTT: We set about doing that record the most ridiculous way ever. We said, "Okay, we're just going to program a real basic drum machine, and we're going to record all the guitars and vocals to this basic drum machine, and then when the vocals are in and all the phrasing's sorted out, we're going to get Rick [Allen] to come in and do all the drum dynamics after the fact so I'm not singing some important line over a drum fill that Rick would've played because he didn't know what was going to be there. We wanted that hole to be left so people are hearing the voice. It might be the line on "Foolin'" at the end of the verse where I go, "I realized that long ago." The drums are there, but they're building up. They're not big drum fill all the way through.

We were writing the drums after the fact. Recording the drums last is not something I was aware of anybody else had really done much. Then, only a month ago, I read an interview with Ian Hunter where on "Once Bitten, Twice Shy" off his first solo album in '75, that's exactly what they did. They recorded the track to a little plunk-y drum machine and then Dennis Elliott came in and smashed the drums after the song was arranged. That's why it works so well. We accidentally learned from the masters there. Maybe Mutt knew, I don't know. Obviously, it was discussed. It was said, like, "Let's try and make an album that nobody else has really made before."

I'll be honest, as exciting as it was, it was also pretty frightening because we knew in our minds what these songs could sound like, but every time we heard them during the day while we recorded, they just sounded really wrong. Because the drums were what you're always used to hearing, going all the way back to Elvis Presley, Little Richard. You've heard this banging drum kit underneath all the noise, and we didn't have that. We had Phil Collins' "In The Air Tonight" ding, ding, dong kind of thing. But because we didn't have a big drum kit underneath, the guys' dynamics within the guitar playing became more obvious, because it wasn't being obscured by drums.

The guitar dynamics were way more pronounced before the fact, and that all adds to the arrangements and why that record is so difficult to replicate. People come up to Phil [Collen] all the time going, "How the heck did you get that sound?" Oh, well, it's two different chords playing the same part. The beginning of "Photograph," we weren't even playing it right for the first 10 years. It's a harmony chord. It's an E and a B chord played together, which one guitarist can't do, obviously. It was only really when [Vivian Campbell] joined the band that we actually started playing it the way it is on the record.

A lot of the stuff went off in the studio [was] like, "People are going to freak when they hear this because they're going to try and figure out how the hell it happened. The influences that we had, like AC/DC for the power and Queen for the dynamics and the variety — the massive harmonies that Queen did — we took that to a much further extent. We found some multi-tracks of Queen's, and we realized that they all sang the same part. If there's a three-part harmony, each harmony was sung by Roger [Taylor], Brian [May], and Fred. It wasn't one did one, one did the other, and the third one was done by the third person. They all did them all, but they only did three or four tracks of each. We did 20 because we really needed to. We wanted this huge size.

We knew it'd be hard to do live, but we got 'round it in the end without tapes by practicing a lot. The fact that Phil's got this wide-throat voice, like a cross between Bryan Adams, Bonnie Tyler, and Rod Stewart — he sounds like 10 people. So that was a big help. When Viv joined the band, because he's a real singer... Steve [Clark] never really sang, so these songs weren't that easy to replicate back in '83. But from '92 onwards, when Viv was in the band, coincidentally, is when people probably started thinking, "They're using tapes," because we got this extra voice. It was just me, Sav, Phil, and Vivian all singing.

But, yeah, the way that Pyromania was put together was backwards, but that's what gave it its uniqueness, really.

RICK SAV: I think because we were so young, there was just a natural enthusiasm and a certain naivete that worked in our favor. We didn't sense any boundaries. We were still forming our own identities as people and as musicians. We never sat down and worked out any game plan. Our only yardstick was to try and make and write and record songs that we would want to hear by other bands, listening on the radio or whatever. That was our aim.

Obviously, we all had favorite bands growing up and we wanted to emulate elements of those bands. But it was more just trying to write the best songs that we could and come up with melodies and vocal ideas. The guitars spoke for themselves. We were always going to be a guitar band because that's where we all originated from — guitar-based music.

What were your initial impressions upon meeting Mutt Lange? Who introduced you?

SAV: I think it was through Peter Mensch, our manager at Q Prime at the time, or one of our managers. He was friendly with Mutt. Mutt had just been doing the AC/DC stuff, which at that point in time were also managed by Peter Mensch and Cliff Burnstein, our other manager.

When we got wind that Mutt Lange was interested in working with us, it was like, oh wow, this is an opportunity too good to miss. We were always fans of artists that didn't just write songs and just record them, we were fans of artists that had a concept and produced records, which is why we were big fans of bands like Queen and Led Zeppelin and AC/DC.

Mutt to us was the perfect producer for us because of his track record at that time, working with bands like AC/DC and Foreigner and the Cars. Just having somebody at the helm that could take what we were trying to do and physically put it down on tape — that was the great essence of working with Mutt.

Phil Collen Joining Mid-Pyromania Recording (1982)

Phil, you famously joined Def Leppard as co-lead guitarist in the midst of the Pyromania sessions. Obviously, the band had its own interpersonal dynamics going. How did you find your way into that?

PHIL COLLEN: I was in a band called Girl, and we were doing similar smaller clubs and little theaters and opening up for the same bands, actually. We'd done Ozzy Osbourne, we opened up for him in England, and Def Leppard were opening up the same tour in the States. So, when I met all the guys, but especially Joe, we had a real similar thing. We had this vision for making this gang — where you could make a hybrid like Thin Lizzy, but [also] Sex Pistols and Supertramp and be a Motown fan and all of this stuff. So, we had a thing there. So, when I joined, I didn't know what the expectations were. We were trying to make something, create something and do something a little bit different, and obviously appeal to the masses.

You want to do that, but we had no idea it was going to do what it did. I remember hearing the stuff, and obviously Mutt Lange had a lot to do with it. He knew how to get it, and we were like sponges and malleable. He could do stuff with us, and we wouldn't go, "No, we ain't doing that," because everything he suggested was amazing. When I joined, it was a really interesting period. MTV was just kicking off, and for us it was a perfect storm because we didn't look like Iron Maiden, we looked more like Duran Duran, but it was a rock band, and we had this heavy chant thing, Pistols or Slade, but we kept it melodic without going too soft, like bands like Styx or Supertramp. It still had a rock edge to it. It was this amazing hybrid, and we realized it sounded different.

Can you talk about merging your guitar dynamic, or philosophy, with Steve Clark's?

COLLEN: What was great is, we were so very different with our approach. I'm very aggressive, I played with metal guitar picks. I had heavy strings, and there's a punk ethos to it. When I first heard the Pistols' album, I was like, "Oh my God, it's the best guitar sound I've ever heard." Steve Jones and flashy guitar players, Van Halen, Hendrix, and Ritchie Blackmore. That was all the stuff that I got into, so it was just very different.

Steve was very Jimmy Page. We had a different approach, but it worked perfectly. Then, our personalities, that was the thing. We ended up being best friends. I think the main thing, you have this goal. We were learning stuff. We lived in Paris for a while, and coming from England, it was very different. It's very cultured, just the architecture, everything about it.

We really got into that, and I think that reflected in our music and how we approach things with the guitar. Instead of going, "Well, let's have a rhythm guitar and a lead. Let's make a guitar orchestration," a bit like Brian May was doing with Queen, overdubbing and stuff.

We also did that with the vocals. That was Mutt Lange's real big thing, and we added another instrument with our vocals. That was fascinating to discover that. The stuff with me and Steve, it was this discovery thing — different types of music culture are everything, and we were experiencing it together while we were traveling around the world. I'm still that way. I really miss that thing that me and Steve had where we would be constantly thrilled to experience some new culture or something somewhere.

"Bringin' On The Heartbreak" Being One Of The First Metal Videos Played On MTV (1982)

Do you think the rise of MTV helped with Pyromania’s success in the US?

COLLEN: Absolutely. It was a brand-new medium that we felt we could exploit. We felt that a lot of the older rock bands that didn't want to do that, they just wanted to be radio. I get that — Zeppelin had that thing, that was really cool. But we wanted to embrace [MTV]. We wanted to be a bit flashy and show it off and let everyone see our gang doing our thing, and the music we were doing was different. We wanted a visual version that people could identify.

So, when [MTV] came out, it'd done all the work for us. It was on a grand scale, you could get this hybrid music with this hybrid-looking rock band, which we didn't realize at the time. You look at other metal bands and they follow a specific kind of lane.

We didn't realize we looked different until we actually got up there. It was more Duran Duran or Metallica. So [MTV] put [us] in a different bracket. Then you had Bon Jovi and all that stuff come out afterwards. But when Pyromania came out and "Photograph," that's the one that really made us a household name in America. It just killed it, and MTV was right there. It was such an important part of it.

First Gig At The Westfield School Dining Hall (1977)

Sav, what do you remember from that first-ever Def Leppard gig? You all were still so young.

SAV: There was an excitement because it was the first show, and we'd been rehearsing for a long time behind closed doors, pretty much for nine months, learning songs, writing songs, things like that. To the point where Steve Clark basically said, "Look, if we don't do a gig soon, I'm leaving. I'm just going to go and find another band or form one." He wanted to go out and get on stage. So, we hastily arranged this concert at this school.

The most memorable thing about it to me was we were doing a song called "World Beyond The Sky," which was the very first song we ever played. Everything was set up, we got up on stage and Steve was the one that started the song with the guitar intro and literally ran to the front of the stage — not that it was a very big stage — but right at the front, threw a big Pete Townsend windmill shape. There was no sound. The amplifiers were on, but his standby was not on. So, he hastily turned around, hit the button, and then proceeded to do the Pete Townsend guitar windmill this time to sound.

So, we were off and running, but it was a bit of a false start to begin with. That was an abiding memory because it was funny and typical in the same breath.

Opening For AC/DC (1979)

AC/DC were a major source of inspiration to Def Leppard in your early days. How was it to actually join them on a tour?

ELLIOTT: We did the one gig with Brian Johnson, but it was on my 21st birthday. We opened for AC/DC at the New York Palladium. They had just released Back In Black, I think. In 1979, August into November, we did about three weeks, four weeks maybe with AC/DC with Bon Scott when they were promoting the Highway To Hell album, and it was unbelievable, really. It was mind-blowing because we were huge fans. We'd all been to see AC/DC. We'd all been down the front to an AC/DC gig in 1977 or whatever. And then all of a sudden in 1979 we're touring with them.

Did you get a chance to hang?

ELLIOTT: Angus [Young] would come into the dressing room and look at the guitars. I think we were in a bar once with four straws and one pint of beer, and Bon Scott went, "Ah, come on, lads," and he bought us a round, or he gave us a tenner or something, and we still owe him.

It was eye-opening. We didn't really socialize with them too much, but we used to watch them every night, and they were just a great band to learn from. It was just a hell of a show really, all from within as well. It wasn't lasers and smoke and screens. All the energy was Angus and Bon Scott, and then the rhythm section of Cliff Williams, Malcolm Young, and Phil Rudd was just to die for.

Changing Name From Atomic Mass To Def Leppard (1977)

Can you walk me through the thought process around changing the band's name from Atomic Mass to Def Leppard?

ELLIOTT: My guess would be that phonetically it sounded good. Pete Willis hated it, by the way. He hated it. He wanted to call the band "Acrisy."

I've never looked it up, so don't ask me what it means. It's probably some scientific term, I don't know, splitting the atom or something. I don't know. But I just remember blurting out as if I had Tourette's, "That's just crap." I said, "Def Leppard, it sounds good." It could have been my enthusiasm won over Tony Kenning and Sav, and I remember Sav going, "Yeah, I think that's really cool," and Tony went with Sav. It was like right there we instantly negotiated, "Okay, we're a majority rules band, three against one." Pete didn't take much convincing. He just didn't like it at first and maybe still doesn't like it now, but he went with it because it's a means to an end. To me, band names, album names are a bit like horses. If you go into the sports page of any magazine and look at the names of the horses, 99% of them are absolutely ridiculous. But if he wins the Kentucky Derby or the Grand National, who cares if your horse is called "Three Men And A Dog"? You know what I mean? It doesn't matter.

But the thing is, "Def Leppard" sounded good. Again, none of us really took much notice of the fact that it didn't actually look good. Tony Kenning was the one that said, "Why don't we spell it the way that it sounds," like Led Zeppelin, I suppose, but it wasn't to copy [them]... We didn't even notice the resemblance to Led Zeppelin until we changed the spelling. But obviously "Def" and "Led" are very similar in that respect.

The way we first did it, Tony crossed the "A" out, and then he put a line down the "O" in "leopard" to make it double P. It was only the first time we'd ever written it out that we saw that it looked a bit like Zeppelin, but we'd already accepted that the band was called Def Leppard, so we just left it like that.

I started writing the logo idea with all the triangular fonts and using the red and yellow because I wanted our logo to pop the way that KISS pops, the way that Yes' Roger Dean font pops, the way that Thin Lizzy popped, so that you use it forever. It really worked. We didn't use it on the first album, but we didn't have much power over what we used. The album cover was just delivered to us as a finished thing because we were naive and young. But by the second album, we're like, "No, we're using Hipgnosis, and we're using this logo," and they went, "Okay."

I had the name in 1975 as part of a school project because I used to do rock posters in art and got fed up of doing real bands, so I started making names up, and Def Leppard was one of them. It was an excitable utterance that I wrote down.

Performing Three Concerts On Three Continents In One Day (1995)

How did you manage to stay awake and coherent enough to play three shows on three continents in one day? Whose idea was that?

COLLEN: The label come up with an idea. It's like, "Hey, we got a greatest hits album. Let's do something stupid." We're like, "Okay." So, we did.

It was amazing. It actually seemed like a week. I think it's 36 hours with a timeline moving, but you have to plan out in each place. We kicked off in Morocco, so that was the African continent part. Amazing. [We played] in a cave, it was just surreal. While we were waiting for the plane, we got invited to this massive Middle Eastern party that was belly dancers and swords... It was crazy. It all seemed like a dream, surreal. Then we're in London, we're playing the Shepherd's Bush Empire, and my mom lived around the corner from it. You can walk to it from my place in London, which I still have, actually.

That was surreal, seeing all of our family and friends from school, and it's like 10 in the morning. Then we hop on a plane, and we finally went to sleep because it was Vancouver — that was the North American part. I absolutely loved it. I really want to do it again. I suggested it. I said, "Look, all we need is someone to lend us a plane, and we could do four of them. We could figure that out and it would be great," but I didn't get any offers. We'll see. But if anyone ever did, we'd be mad for it again.

Playing In David Bowie Tribute Band Cybernauts (1997)

https://youtube.com/watch?v=3qq1I8QRhYo /wp:paragraph -->

I heard something about Cybernauts planning to finish an album — one Joe first mentioned in 2012. Is that still happening?

COLLEN: We are going to finish the album. We've got some other songs that we're going to [record]... They're all Bowie-era, so "John, I'm Only Dancing." We spoke to Woody Woodmansey, he was the only remaining member of the Spiders From Mars.

Mick Ronson, who was David Bowie's guitar player, passed away in the early '90s, and we'd done a benefit concert, Hammersmith Odeon in London, and we got to play with Woody Woodmansey, Trevor Bolder, who were the original Spiders From Mars with Mick Ronson, and it turned into something. I said, "Wow, wouldn't it be great if you'd done a gig?" So we did another thing up in Hull. They did a recognized benefit for Mick Ronson. Then we got into doing a tour. We actually toured England and done some Irish shows, and then we was up in Japan.

We recorded a whole live thing, and it was so much fun. Me and Joe were obviously huge, huge, huge Bowie fans. It was a 'pinch me' moment. We are playing these songs with our heroes, and I listened to Aladdin Sane, Hunky Dory, and Ziggy Stardust all the time still, they're my three favorite Bowie albums.

Performing On CMT Crossroads With Taylor Swift (2008)

Taylor Swift is on the record as being a huge Def Leppard fan. How was it to perform with her on CMT Crossroads?

COLLEN: What was lovely about it is that she'd gotten into [our] music because her mom and dad played Def Leppard all around [the house], and Shania Twain, so obviously the Mutt Lange factor is in there.

But her songs, they fit in very easily to what we were doing — like the chord structures and the sounds of it, it was so easy to adjust into it and play along with her and her band. It was like, wow, this really works. We had a blast. And she was great, and obviously [she's] the biggest star in the world right now. It is crazy.

[She's] very ambitious and determined, and I love that. Because I got that kind of vibe myself. I really applaud her for doing that. She works so hard. You can't say enough about it.

SAV: It was fantastic. We spent a week together. It was a great experience. Her band were fantastic, as was Taylor. I mean, people realize what a superstar she is now, and she was pretty big then. For somebody of such tender years to have written so many songs by the time she was 18, it was incredible.

I suppose at the time she was a fan [of ours]. But she grew up without any choice because it was her mother that was the big fan. She was almost pummeled to death with Def Leppard from, well, probably from in the womb, as it were. But yes, she couldn't escape us. I guess eventually it was either go mad or like us, and I think she chose to like us.

It was great to play some of her songs, but also some of our songs with her singing along with Joe, it puts a different slant on everything. You understand that some of the songs you've written can translate in different formats. That's what made it fun more than anything else — bringing a little bit of Def Leppard into her songs, which would've been cool for her and her band too.

I assume you've been approached by a lot of artists over the years telling you what big fans they are of Def Leppard. Have any surprised you?

SAV: Yeah, throughout the years there's actually been more than we care to appreciate, really. A lot of the bands that, certainly in the noughties, would come to us and say we were really inspirational when they were getting together, that our early albums inspired them. I can't even remember most of them to be perfectly honest, but they were all a little hardcore. They were that noughties nu-metal that was more extreme than we've ever been. It was like, "Whoa."

Guys would come up to us and they'd be almost gothic and a little bit frightening, and you think, "Oh, Christ, they're going to have a right go at us here, they're going to call us pansies and wimps and that type of thing. They're going to think that we're in bed with bands like Journey and R.E.O." It's actually quite the opposite. It's like, "Dude, High 'n' Dry, that made me want to pick up a guitar."

It's actually quite flattering in a sense that even our early stuff influenced a whole range of people from the nu-metal guys to artists like Avril Lavigne. When she was starting, she would say, "Yeah, I would listen to your records." It's a real compliment. You just don't know what you're doing when you're creating records. You don't know the effect that they're going to have on people 20, 30 years later.

That's hysterical about the nu-metal groups.

SAV: Yeah, Disturbed and bands like that. It was just like, really?

This is hot off the press, but we have just mastered a one-off single, and playing on it is Tom Morello from Rage Against The Machine, who was a huge fan back in the day when he was growing up. High 'n' Dry was like his Bible. He's playing a solo on our new single, it's going to be out there pretty soon. That's just another example — you keep passing the baton around, and it's fantastic.

Developing A Def Leppard Animated Series (2009)

Is it true that, at one point, Def Leppard had agreed to be the subjects of a (now-shelved) animated series?

SAV: You know what, I'd completely forgotten about that, but I think you're right. Now you've just turned a cog in my memory.

This didn't come from the band — this came from outside as an idea. But yes, there absolutely was an idea floating around to create five characters that were us, and it was Def Leppard, but in cartoon form. How they were going to save the universe through doing dastardly deeds or whatever it was.

It never really saw the light of day. You do get a lot of things thrown at you, just different ideas from outsiders saying, what about this? What about that? Some of them you go, I don't really care, but let's take it to the nth degree and if we like it, we'll run with it. But for whatever reason it never really took off the ground, that cartoon thing.

Finally Streaming Their Classic Albums (2018)

It famously took Def Leppard a long time to get their most classic albums onto streaming platforms. Now, with your label UMG pulling out of TikTok, do you have any feelings about your music not being accessible to fans on that platform?

ELLIOTT: Well, the history of this is, you have to think of Universal Records as an umbrella. That umbrella, say it's one of those that you can borrow from the lobby of a hotel. Many different people have been under that umbrella. In 2008, when we first negotiated with Universal to go digital, the deal was reneged on by the then-regime. Then, of course, we threw the toys out of the pram, and we said, "Well, okay, fine, we'll go our own way. We'll rerecord like Taylor [Swift]'s doing." We did that for a while, and they kept coming back to the table, and we kept saying no. Eventually, the offers kept getting better and closer to what the original offer was. Howard Kaufman, our manager at the time, said, "This is as good a deal as you're going to get. I think we should go with it."

By then, the people under the umbrella of Universal were on our side. These were good people that used to maybe work lower down in the trenches in the past that are now in charge. They're like, "We love you guys, come back." I think we announced the deal January 2018, and within three years we were over four billion streams, and we're over six now, pushing seven even, I think. It's been an amazing journey for us to play catch-up and finally be in the big numbers. As regards TikTok, as far as I'm aware, every artist on Universal can no longer be found on TikTok-

Correct.

ELLIOTT: ... Because they're going through some, what sounds to me like, heavy negotiations. My theory is it's temporary. I'm sure it'll all come back. We survived not being digital until 2018, and we still had an audience out there because, with social media, if you can't get our music, people were either trading it or they already owned it because they'd bought the vinyl. Then they bought the cassette, then they bought the CD, and they were still playing their CDs. Now, of course, we're on every Spotify, Apple, whatever server you want to use.

As for the TikTok thing, I don't know what the answer is. I'm not in that negotiation, but if Taylor's not there and U2 are not there and all the other artists on Universal like ourselves, I'm sure they'll be back soon enough. I think it's like everything else. I think if you go to the supermarket for a tin of beans and you get to the shelf and it's empty and you go, "Ah, damn it," you go, "Oh, well, okay, so I'll buy hula hoops." You just get on with it until it comes back. You just find a way around it. You know what I mean?

Most people have probably got our music downloaded, so if they're that desperate to hear us, they don't need to go to TikTok for it. They can go to our website and look. They'll find another route to listen to us if they're that desperate to hear us, and if they are, I'm grateful that they care enough to keep looking. Who knows? Like everything else, something's really hot and then 10 years later people can't remember the name of it, like Napster. It doesn't mean anything anymore, and it was such a big deal when Lars [Ulrich] took them to court and all that kind of stuff. Maybe TikTok fades away anyway and something else comes along. I don't know.

At the end of the day, it's all down to the money. If you're going to watch an artist 10 trillion times on a certain thing, artists still deserve to be paid. So, I get it. But it's out of my wheelhouse to come up with a solution that suits every party, because at the end of the day I'm just the guy that tries to rhyme "maybe" with "baby" and see if I can get away with it.

Pyromania (Deluxe 40th Anniversary Edition is out 4/26.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!