We've Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

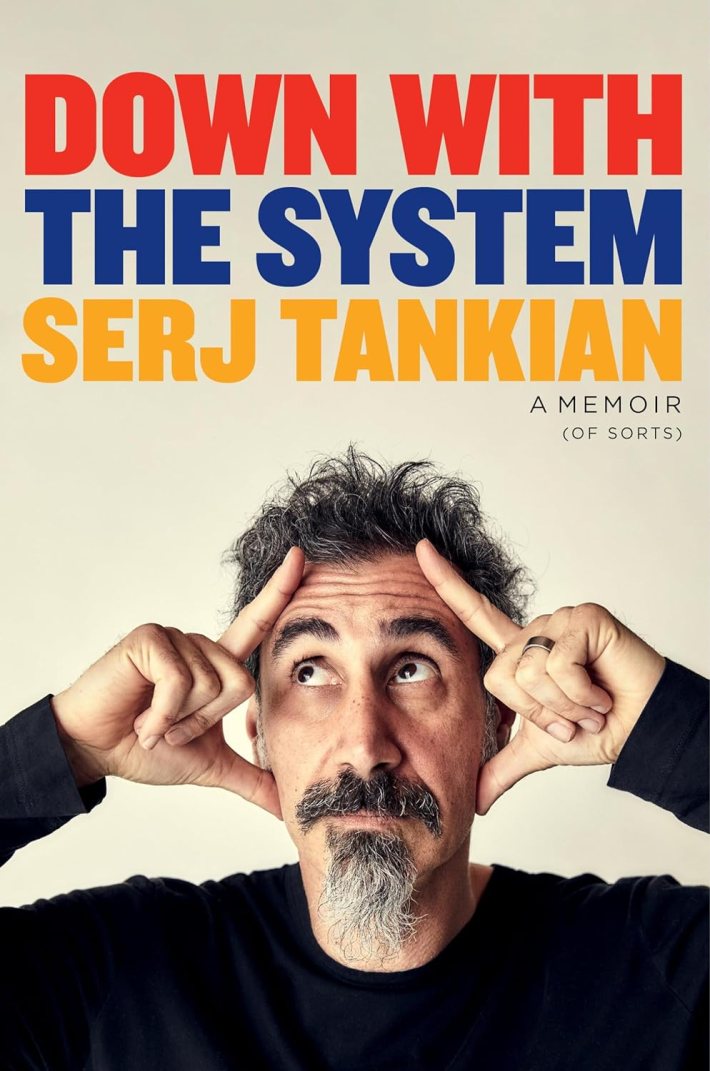

On 9/11, System Of A Down topped the Billboard 200 with their iconoclastic sophomore album, Toxicity. Just two days later, its lead single, "Chop Suey!," was banned from radio by Clear Channel, now known as iHeartRadio. Serj Tankian, the band's frontman, is aware of how poetic and political this occurrence was, just as he's aware of the poetic and political aura of his music. Out today, Tankian's debut memoir Down With The System is rife with trenchant insight and riveting stories, including the one above that serves as the book's introduction.

From briefly owning a software company to learning the intricate US legal system when a civil lawsuit left his parents financially bereft, Down With The System traces Tankian's storied life thus far. He provides geopolitical context on the Armenian genocide perpetrated by Turkey in the early 20th century, details a free System Of A Down show that the LAPD turned into a riot, and describes overcoming writer's block with Rick Rubin.

For this edition of We've Got a File On You, Tankian delves into some of these anecdotes he covers in the book, and he touches on other topics, like almost appearing on an Avicii album, the many covers of "Chop Suey!" that have sprouted over the years, and Imagine Dragons ignoring his request to cancel their performance in Baku, Azerbaijan. Read our interview below.

Down With The System (2024)

Why did now feel like the right time to write this memoir?

SERJ TANKIAN: Because someone asked me to. [laughs] I had a literary agent from London reach out with the interest of an interview I've done with The Guardian, a political interview about what's happening in Armenia. They called to see if I would be interested in doing a memoir. At first I said, "Listen, I don't have that in mind. I want to write a book about the intersection of justice and spirituality." And then after talking a while, we realized that both were possible simultaneously, and it became a memoir of sorts in that sense. It's one of those things where, when you have an opportunity to do something, you sit down and think about it and go, "Is this something I really want to do?" And if you're excited about it, then the answer is yes.

What was it that excited you about it?

TANKIAN: The ability to dive deep into my own past and my family, and make certain connections and learn certain lessons, learn new things. It was a way of stopping. You get to think about your life, or your family's life or where you come from, so it was a nice way of doing that in a very long format.

What kind of overlap is there between writing lyrics and writing a full book?

TANKIAN: We're doing an EP called Foundations, which is music from different eras of my career. We're starting with the release of a song called "A.F. Day" that's at least 25 years old. They're from early System days that I've never worked out with System and [they're] punk rock, kind of metal, heavy songs. So I mean, how do they interrelate? I don't know. I don't see music or lyrics interrelating much. I've included them within the memoir, in terms of reflecting back and doing some explanations, but I don't know how else they relate.

Giving Up Law School Plans To Pursue Music (1989)

Something that stood out to me in the book, and this is a nice segue for our next topic, is when you're talking about driving back from an LSAT class. And you decided law school was not for you and that you wanted to do music. What was going through your mind?

TANKIAN: I was working with my uncle in the Jewelry District in downtown Los Angeles after graduating university, and I knew that wasn't my calling. So I was looking for something that would be my calling. And at the time, I was playing music, but I didn't admit to myself that was my vision. My parents were dealing with a very lengthy civil lawsuit, and I was dealing with lawyers, firsthand briefs, and learning a lot about the law firsthand. And so I thought, "Hey, I can do this. I'm already in the middle of all of this, dealing with lawyers and whatnot, learning a lot about law."

So I went to take an LSAT class after working all day in downtown LA. I drove to Long Beach, which is quite a distance, and everyone there was really delighted to study law. That's what their vision was. That's what they were excited about. I didn't really love lawyers. I was having a hard time, and it was just this confounding thing of, "Why am I here? I feel dumb," and I was driving my Jeep Wrangler back home. I was on Laurel Canyon, and it was raining; it was just this really dramatic evening. These emotions came, and I had this epiphany where I literally hit my brakes and stared at my hands and I said, "I don't want to fucking do law! I want to do music!" I always had to go to the far reaches of who I will not be and who I'm not meant to be for me to admit to myself who I really am. And in my case, that's how the breakthrough was.

Pre-SOAD Band Soil (1992)

What have you learned from that time in Soil?

TANKIAN: I always referred to it as the broth within which System Of A Down was cooked. We had this phenomenal drummer named Domingo [Laranio]. He was from Hawaii, and he had a lot of knowledge. He had a lot of songwriting experience, and he worked very closely with [SOAD guitarist] Daron [Malakian]. It was my first time singing and writing lyrics. We lasted for eight months; we had one show; and then Domingo had to go back to Hawaii. And so we folded that band, and that was the beginning of System Of A Down. It is the foundation on which System was based. In fact, we even have some songs that are derived from longer, crazier versions of those songs from Soil.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

Owning a Software Company, Ultimate Solutions I (1995)

What was it like to own a software company?

TANKIAN: I started it because I realized that if I worked for someone else, I'm not going to have enough time to do music. If I had a day job, I was going to be too tired to work on music, so I thought, "How can I make an income?" At the time, myself and my parents were going through a kind of a tightening of economic conditions based on the lawsuit that was prevailing. When I was at my uncle's firm, I helped him create a vertical industry solution for his company with a programmer. So I reached out to that programmer and thought I could sell this to other people that I knew in the industry and started my company that way, eventually developing my own vertical industry, modular accounting software, specifically all for jewelers. It was actually really successful. I started doing really well. Problem is that now I have my own company that's taking up all my time, and I still have not enough time to do music. So I had to dump my company, I had to sell it. And that wasn't an easy task. But I eventually was able to do that.

Was it a similar situation to when you decided to not pursue law school? Where it was a real commitment to pursuing music?

TANKIAN: In that sense, yes. But I enjoyed developing software way more than law. And I really thrived. I actually love software. I've recently invested in a company in Armenia, called AAA Audio that is creating new virtual instruments for composers around the world. But I knew that my main calling was music, so I didn't want to sacrifice my vision for it. So selling the company gave me just enough income to be able to survive until I got my first publishing check. That gave me enough to survive on tour for the first year or two until we got paid again. It's all just little bridges until you get there. But it worked.

"P.L.U.C.K." (1995)

This is the first recorded SOAD song. How do you feel looking back at this song? Do you feel like it's a great example of what System does?

TANKIAN: It's really interesting because "P.L.U.C.K." was such an earlier System song, and it obviously had to do with the our Armenian roots and our wishes for the world to properly recognize the genocide of our ancestors. The heaviness of it is very much based on Soil because time-wise, it was very close. It was one of our first songs. And so it's a very heavy progressive metal kind of vibe with the chorus and very political. So coming out of the gate, that was our thing. And that's interesting. Thank you for reminding me because I forgot that was one of our first songs. And that is technically the first song we've probably ever recorded.

I was wondering when we were talking about Soil if "P.L.U.C.K." was one of those tracks that transferred from Soil into System?

TANKIAN: I'm guessing it is but I would have to double check. It's been so long, Grant. It's been over 30 years! So I would have to check.

Playing Ozzfest for the First Time (1998)

What do you remember about playing that for the first time?

TANKIAN: If you look at Ozzfest between 1998 to the early 2000s, it shows the growth of System Of A Down because we started on the second stage at probably the worst starting time, like we probably were rotating between noon and 3 or something like that, between different baby bands like ourselves. I remember it well because that was our first festival tour, and that was different. We had opened for Slayer before that. I think that the only tour we had done before that was opening for Slayer in the US and in Europe. Playing Ozzfest was exciting because now you're in the middle of a field somewhere and there's like 3,040 bands there and you meet all these different artists and watch their shows and hang out, make friends, and play basketball backstage. It became much more socially viable than just touring by yourself.

It wasn't quite as lonely.

TANKIAN: Exactly. It was much more fun. It was more exciting. And then the second time we played we opened the main stage if I'm not mistaken. We had graduated to the first stage as an opener. The third time we played it, we headlined if I'm not mistaken, before Ozzy. The fourth time we played, if we did play a fourth time, we just headlined if I'm not mistaken. Again, memory's a little shoddy. But that's how I remember.

Playing "Spiders" for Their Late-Night TV Debut on Conan (2000)

Do you feel like this wasa pivotal moment for you? Did you feel any sense of pressure?

TANKIAN: No, not really. I mean, pressure, yes. But not because it's a pivotal moment. It's because you assume there's millions of people watching, and that's scary. I think we performed really well, and it was so dramatic that I remember at the end I was on my knees, just like this dark vibe, wearing this eyeliner and this long gown, and Conan comes up to me and he looks at me and he goes, "It's all gonna be OK. Don't worry about it. It's all gonna be fine." [laughs] It was the funniest thing he could have said. I cracked up so hard! That's what I remember from that TV spot. He's just like, "It's all gonna be OK. Don't be so gloomy." It was pretty funny.

Clear Channel Banning "Chop Suey!" After Toxicity Tops The Billboard Chart (2001)

You open your book with the story of topping the Billboard album chart on 9/11 and then getting banned by Clear Channel. That's such a big combination of things to happen to you at once. What were you feeling during that time?

TANKIAN: Stressed. The release of Toxicity being on the week of 9/11 was absolutely mind-blowing because none of us was really thinking about the record. It felt like the world was falling apart, and the fact that I'd written a geopolitical essay analyzing what was happening and posted to the band's website that got a lot of reactions and anger elevated all of that stress. Before that, also, I should mention that we had planned a free show behind the Roosevelt Hotel in Hollywood at this huge, open area. So many people showed up to this free show that the fire marshal had shut it down and a riot started. I don't want to say we caused an LA riot, but I think the bad decision-making of the management of the LAPD led to a Los Angeles riot, which was also incredibly stressful because we're watching our fans being arrested and beat up. So that's what Toxicity’s release was for us. It went from that riot to 9/11 to "Understanding Oil."

A week after being on tour, all these threats were coming in. If you remember at the time, it wasn't just 9/11. On TV, they were saying to be careful at large gatherings and all this stuff. And every night we had a large gathering. We were touring. It's not the way you would perceive putting out a hit record and hitting #1. I always tell people, it's the weirdest thing that on 9/11, a band called System Of A Down had a single that was #1 on the Billboard charts in the United States, and the single was singing about self-righteous suicide. It's mind-blowing, right? And yes, it was taken off the airwaves by Clear Channel, along with many other songs obviously. It was just crazy, man. Just crazy.

Interviewing His Grandfather, Stepan, About The Armenian Genocide For The Documentary Screamers (2006)

What did that experience mean to you?

TANKIAN: It was very important to me because he was a survivor of the Armenian genocide. He had told us the stories of his family and how they had perished and the whole story of the genocide. Growing up, he had shared it with us as we were ready to listen to it, age-wise. He was an activist himself, someone who had been a community leader and worked hard for Armenians in the diaspora. It meant a lot for me, for people to understand his story. The US government didn't recognize the genocide, so it was important to pay respect to survivors. I was able to get a full life story from him on camera.

Winning His First Grammy for "B.Y.O.B." (2006)

Did it feel like a moment of validation for your music? I know you had already started to check out of System by this point.

TANKIAN: A few years earlier, they had nominated us for a Grammy and asked us to play at the Grammy Awards. At the time, Daron and I both just went, "No, thanks." I guess it's the punk rock attitude that you don't really need someone else's praise, that kind of thing. But, then they give us one two years later without showing up anyway. So it was nice. It's something you can write in a book: Grammy award-winning author. [laughs] But it is what it is. I could name 100 bands that haven't received Grammys that are really important to music, but it is what it is.

His First Solo Album, Elect The Dead (2007)

How did it feel like making a solo record after being with System for all that time?

TANKIAN: It honestly felt really invigorating. It felt great because I felt like, especially within the last few years of the band, that I had a lot more ideas than I could put through that then I could work through the band. There was a creative schism with them in my songwriting, at least from my perspective, and I felt like I couldn't get everything through that I wanted to within System. When I was doing Elect The Dead, my first solo record, I had this renewed vigor for songwriting and creating, and I really thrived making that record. It was a whole different process, of course, because you're doing it by yourself. You don't have any bandmates. So it's a different process of writing, recording, and demoing, and I loved it. The success of that record and my career opening up on its own outside of System gave me the missing…

Confidence?

TANKIAN: Yeah, as a songwriter, as a performer, as an artist. When we started working together with System, I was at a different level of assertiveness and confidence than I was when I left System in 2006 when we decided to take a hiatus.

With Elect The Dead, in particular, what did you enjoy most about making that?

TANKIAN: When you're writing a song, exactly every element of it, from instrumentals to lyrics to the video, you want to make. Everything about that song and that record, if you have a complete idea, it's nice to take input from others that you respect artistically. But ultimately, you gotta make that decision because it's your own thing. I like being able to just make the decision on my own, without having to run it by a committee and have it changed because someone felt like this part was maybe too mellow, or this part may be too this or that. That part to me was invigorating and emancipating.

Again, not that I didn't play it for people and take input I did with every solo record from people that I respect. I'll play it to take input, weigh it, but ultimately make the decision myself, and it felt good doing that after being in a band for so many years. That was nice. When you write partial music, like if you have a partial vision for an artistic endeavor, and not a full vision, then a collaboration is incredibly helpful and necessary. But when you have a full vision of what you want to present, then sometimes it might get in the way.

Receiving A Commemorative Medal From Former Prime Minister Of Armenia Tigran Sargsyan (2011)

I imagine you probably had some really complicated feelings about this.

TANKIAN: I did, yeah. I was dealing with a post-Soviet, corrupt government. I didn't want to authenticate them by accepting something like that. However, I also thought through it, and I thought, "Wow, this might be an occasion for me to actually have a real conversation with someone in power there and let them know some of the things that we, as a diaspora and Armenians, think is wrong with the situation there, even though that sounds very presumptuous. So I took that occasion and accepted their gracious gift of that medal of freedom. And I had a really nice, one-on-one private conversation with the PM at the time. We talked about corruption; we talked about Armenia's energy reliance on food production. I asked a lot of questions. I also made it clear that the long-term devolution of corrupt practices and the oligarchic system within the country was going to be harmful for our people and that we were all aware of it.

Almost Appearing On Avicii's Rock Album, Stories (2015)

TANKIAN: No one's brought that up. Interesting. He was a really, really sweet guy. I feel so bad that he passed the way that he did. I had many offers to work with DJ songwriters before. Sometimes, I'd hear a song and go, "Yeah, that's not for me." And in his case, I thought to myself, "I just want to meet the guy and see if something comes out that we can jam on and elaborate into a collaborative effort." So I met him at A&M Studios in Hollywood, and we had a nice hang, and I played some music. I sang some stuff. He was putting it together. It never fully panned out. I remember seeing him and realizing he looked tired. He mentioned that he was having some health troubles and issues. And he was so young. He was in his early 20s. And I looked at his career and the pace at which he was going, and I remember telling him, "Pace it, dude. You can be around for a long, long time doing this. Pace it. Don't let other people and their greed or influence push you too hard. Do what you'd like to do. But you don't have to do two shows in one night or whatever." Like, he just looked tired. And I'm like, "This guy's in his 20s. Why is he tired?" I remember that, and it's unfortunate how it ended up.

Paying Tribute To Chris Cornell With Remaining Audioslave Members In Prophets Of Rage (2017)

How have Chris and Soundgarden inspired your own work?

TANKIAN: Chris was always one of my favorite rock singers. Growing up with the Seattle grunge scene, I loved his range. I loved his intentions behind his vocals. Years later, when I got to meet him in person, I was very grateful. We became friends and hung out a number of times. He came and visited us on our farm in New Zealand one time, and we hung out in LA, and I love his family. It was really difficult singing his song with Audioslave while we were on tour, within the year that he passed. We were all tearful, but we wanted to pay homage to our friend who was an incredible icon in music. It's very rare to have artists where, no matter what genre they're in, that when they perform you feel every note; you feel every word. And that was Chris, a really sad loss for us all.

Starting His Own Coffee Company, Kavat (2018)

How did you get the idea for this?

TANKIAN: My grandmother and my mom used to make Armenian coffee at home and have a conversation, and that smell would waft throughout the house when I was a young kid. Since then, I've loved the smell of coffee. If I walk somewhere, I love going to cafes. I love ordering coffee because I love coffee, but even if I didn't order it, I would just walk in and sit there and smell it. And I love it. It makes me feel good, like the vibe of coffee, the smell of coffee. And so I wanted to start a coffee line of my own and introduce organic modern Armenian coffee. We started a company called Kavat, along with some partners in 2018, and we've been going at it since. We're about to open up a cafe gallery in Eagle Rock, California in the next month and a half, and we'll be a flagship store for Kavat Coffee.

Covers Of "Chop Suey!" By Tina Fey And The Iguana Lady In Sing 2 (2018-2021)

Many covers of "Chop Suey!" have surfaced over the past few years. There have been some really wild ones. One of them is Tina Fey on SNL in 2018. Have you seen it?

TANKIAN: I have, yeah, a long while ago, but yeah, I have. That was great. There have been a lot of little moments of covers. One of my favorite ones is Jack Black's, when he just kind of makes shit up, and he's so great. But yeah, there have been a lot. There are some really cool South American players that have done a cover of it. Recently, I saw a woman — I'm trying to remember her name — but she was playing children's musical instruments and singing about diapers.

@bigmerla ????? Crib of Rock @systemofadown #chopsueysystemofadown #chopsuey

♬ original sound - Big Merla

My friend sent that video to me!

TANKIAN: Oh my God, everyone's been sending it to me! [laughs] It's genius. I love that I've been a part of something that's been communicated so widely that it has become part of people's culture. I think that's beautiful.

Another one that stands out is the iguana lady in the movie Sing 2 by the people who did Minions. Have you seen that?

TANKIAN: Oh, yes, I have seen that. Yes, I have. [laughs]

On a related note, what do you and your kid usually listen to in the car together?

TANKIAN: We've been recently listening to this rock instrumental band called Dance With The Dead. I took him to one of their concerts in Orange County about six months ago, and he's loving it. He's really into metal right now, but we play him everything from soundtracks to pop music to hip-hop to jazz, but he's in his metal phase right now. He thinks he's cool because he likes metal. [laughs]

Publicly Requesting Imagine Dragons To Cancel Their Show In Azerbaijan, Only For Them To Perform There Anyway (2023)

Last year, you asked Imagine Dragons to cancel their performance in Azerbaijan, but they did it anyway. Why do you think divestment from oppressive colonizers, whether that's Azerbaijan or Israel, is an effective form of political protest?

TANKIAN: Because proof is in the pudding. Anytime that there's an economic blockade against such a country, that will affect it greatly. It makes a big difference. Divestment does make a huge difference. In a global economy, nobody wants to be isolated. No country wants to be isolated. No country leader wants an arrest warrant at the ICC, no matter how powerful they are, no matter how many weapons they have. Nobody wants to be isolated from the world community. And that is exactly why divestment sanctions make a big difference.

Azerbaijan attacked Armenia in 2020; they did an ethnic cleansing and a nine-month blockade that the UN's International Court of Justice had to decree against it, asking them to open up the illegal blockade. They were trying to starve 120,000 people in their historic homelands for thousands of years.

And in September of last year, two weeks before Hamas' attack, Israel and Azerbaijan attacked Armenians and ethnically cleansed them and left them as refugees. In Armenia, these people whose ancestors have lived there for thousands of years, left their homes, left everything, left the graves of their ancestors to a dictatorial regime in Baku. So knowing that, if a band or Formula 1 or COP29 decide to do their event there, then I guess it would have been cool to do such events in Nazi Germany. I guess it's cool to do it in Russia now, why not? Why say it's not OK to do it in one and OK to do it in the other? Anyone that does ethnic cleansing and genocide needs to be fucking punished. So that's why I got pissed off. Some artists are artists and some artists are entertainers, and I'll leave it at that.

Down With The System is out now via Hachette.