- Locked On/679

- 2004

My favorite song on A Grand Don't Come For Free is "Wouldn't Have It Any Other Way." Over a skittery percussion loop hinting at drums and bass and a keyboard line that refuses to develop into a phrase, Mike Skinner depicts the experience of kicking it at his girlfriend's house. The Birmingham native should be meeting his mates at the bar, but he'd rather relax with a spliff and watch EastEnders. His motives aren't pure: He admits his own TV's busted. But the way the music stops and starts complements the repetitions in Skinner's lyrics. He could be convincing himself of a domesticity he doesn't believe in; the next song, "Get Out Of My House," records the couple's first fight. But mostly Skinner's everyman daze — like Bernard Sumner's in New Order's gorgeous 1989 song "Dream Attack" — is affecting. Reluctant by nature to issue statements, incapable of flourishes, he lingers on the banal. That's what you do when you're getting high on a Saturday afternoon with your girlfriend.

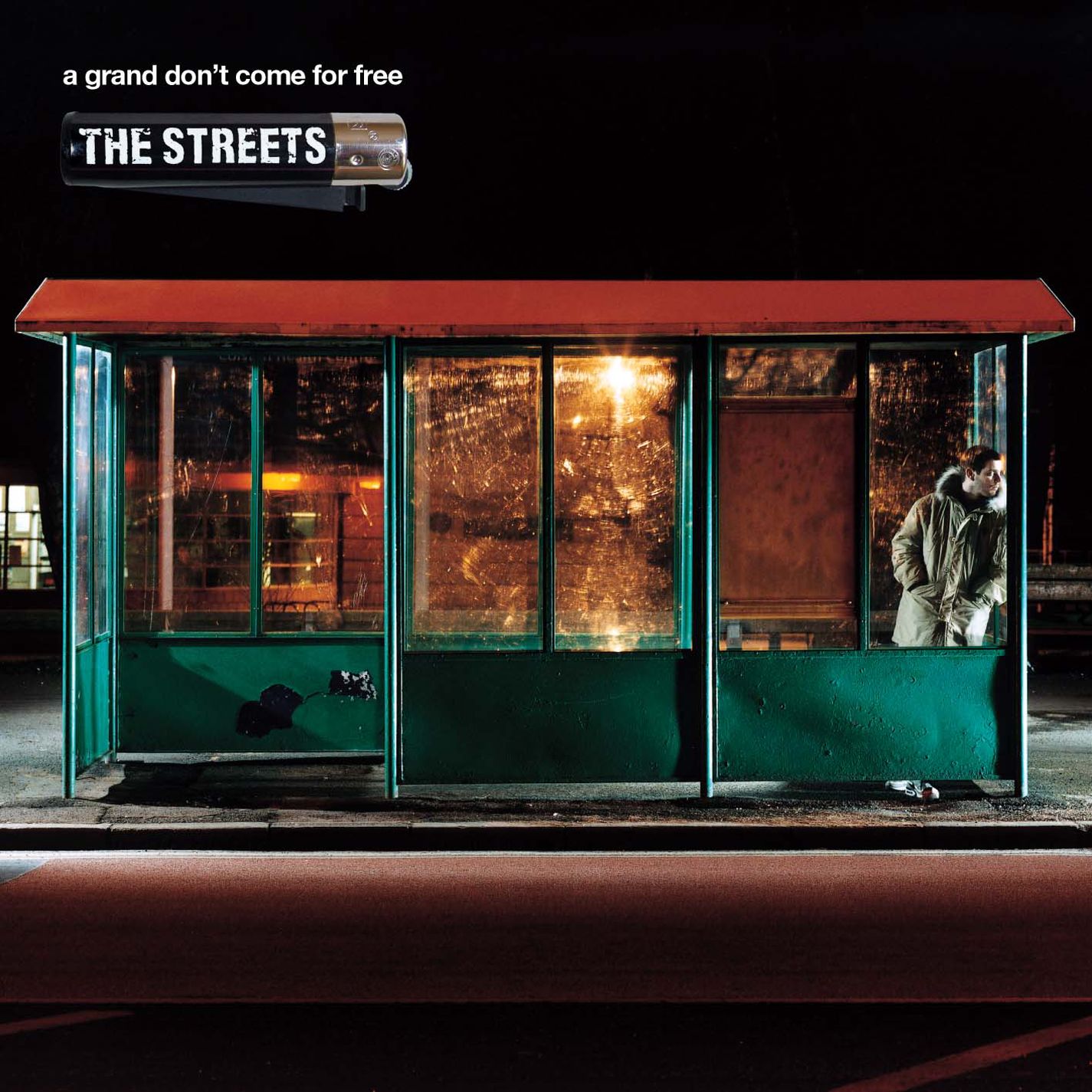

Skinner's second release under the Streets moniker presents itself as a concept album. It has a narrative. A bloke loses £1,000, starts dating Simone, breaks up, gets hammered, regrets it, and finally fixes the damn TV at the same moment he finds the missing money. That's it. Concepts need no grandeur (every album is a concept album: love lost, love found, etc.). Two years after his debut Original Pirate Material turned into a surprise hit, A Grand Don't Come For Free crystallized Skinner's strengths and weaknesses. It worked. UK listeners made A Grand Don't Come For Free a sensation: it peaked at #1 and sold an impressive 1.4 million units. Even in the US, where Anglophilia surges in unexpected times, it charted at a respectable #82. Perhaps the buzz around bands like Franz Ferdinand transferred over to the Streets, though, of course, the Glasgow quartet's conspicuous glamor and attraction to riffs as sharp as their pant creases could not be more different from Skinner's wrinkled shirts andpreoccupation with burgers and chips.

Listening to A Grand Don't Come For Free was for many Americans their first acquaintance with grime, which took the breakbeats of garage and chopped them up and scuzzed them up with blips and bloops from video games and with thick woozy keyboards. Releasing material at the same time as the Streets was Dizzee Rascal, a Londoner whose 2003 album Boy In Da Corner and its 2004 followup Showtime lean harder on the atonality and commitment to surface lyrical detail. Rascal, a more resourceful producer and collaborator, had the more interesting career, but in a landscape where American exports like Justin Timberlake and Beyonce competed with the likes of Muse and Dido, A Grand Don't Come For Free didn't sound like the future so much as the present: a battered flip phone camera's capturing of a hardscrabble, very white, very male point-of-view of getting by in Tony Blair's England.

In A Grand Don't Come For Free Skinner doesn't hide his influences. Bits of the performed laddishness of Parklife-era Blur ("Fit But You Know It") and the locomotive vulgarity of Eminem ("Such A Twat") flit by, but his flow, insofar as he's got one, is his own. How listeners respond to this album depends on their tolerance for his thin, pinched vocals and wariness with melody. At the time A Grand Don't Come For Free’s loudest partisans in my crew were guys who didn't much listen to hip-hop. (I was one of those fools.) In the year of Madvillainy and The Pretty Toney Album and Purple Haze, Skinner's album almost came off as a wan white boy parody. Cam'ron boasts about drinking saki on a Suzuki in Osaka Bay; Skinner has to put what's left of his money on a football match.

To enjoy A Grand Don't Come For Free is to accept — make peace with — Skinner's insistence on mixing himself into prominence. Reviewing "Dry Your Eyes" for his Populist blog, Tom Ewing wrote the following:

Skinner doesn't sound like any other British rapper, mostly because nobody else who spins out chat like he does calls it rapping at all. If he'd surfaced two decades earlier on the post-punk fringe, or two later rubbing shoulders with Dry Cleaning or Yard Act, what he does as a vocalist might make more sense: lock down your aerials, you're listening to the sprechgesange.

On its strongest tracks, like "Fit But You Know It" or the eight-minute closer "Empty Cans," he relinquishes control; he lets the beats threaten his dominance. Hence the superiority of Original Pirate Material, which in retrospect flaunts the I've-got-this authority of a second album; A Grand Don't Come For Free, by contrast, plays like a series of attitudes and postures with which artists experiment on debuts. To my ears Skinner has never surpassed Original Pirate Material’s first track "Turn The Page." It begins with a two-note synth line, a jungle track; then a classical motif replaces the synth. "That's it, turn the page on the day, walk away," Skinner proclaims. By the time "Turn The Page" ends it's as if a generation of British music — from the Specials' "Ghost Town" and Massive Attack's anxious symphonies to Pulp's Jarvis Cocker making his "I"s resonate like "we"s — had paraded down a catwalk and been dismissed.

Stumbling on tunes instead of writing them is a phenomenon that Skinner works to his advantage. The staccato guitars on the single "Fit But You Know It" would seem to impede melodic development until Skinner pulls out a singsong chorus: a shrewd choice given how the song's rhythm mirrors its tale of a drunken on-the-rebound Skinner, emotions and hormones a-whirl, hits on a girl who's too good for him. The Eminem-indebted "What Is He Thinking?" is lurid paranoia set to music, about Simone who may or may not be cheating on him with a guy named Mike (played by Wayne G, Skinner's Nate Dogg).

One of the impressive things about grime is how female points of view responded to the male vocalists. My favorite part of Dizzee Rascal's debut single "I Luv U" is when Jeanine Jacques, mimicking his cadences, calls him a prick after he's called her a bitch (Jeanine Jacques apparently didn't think much about Dizzee's production). To Skinner's credit he doesn't explain Simone; he cedes space for her in "Get Out Of My House," where guest C-Mone (geddit?) voices her, throwing him out of the same apartment where one song ago he was cooling it with a spliff. The UK #1 "Dry Your Eyes" is prose set to music for better or worse. The acoustic guitar and a treacly violin signify realness; he Really Means It Now. You can understand why, to quote Skinner, Simone's eyes glaze over: he can't stop justifying his selfishness. When he suggests an open relationship "if you must," her resolve to leave hardens. Whether Skinner wants listeners to sympathize with the kind of male sensibility that believes love should last forever (and thus it's her fault for ruining his purity of vision) or to note it remains a question. For me, the track's similarity to Milli Vanilli's "Girl I'm Gonna Miss You" presents another problem.

Skinner remained dry-eyed about his career. 2006's The Hardest Way To Earn A Living has some of his most nimble rapping wasted on tracks about the inexhaustibly boring subject of whether fame makes him less fuckable. Last year's The Darker The Shadow The Brighter The Light, his first album in a dozen years, is a veteran's release, taken for granted despite the handful of bangers. The Streets had a couple of moments when many acts get just one. Besides, as life gets harder for the young and poor around the world, a 50-minute not-quite-spoken-word album chronicling a sustained freakout about losing a thousand quid isn't such a banal idea. In 2024 we're unfit and we know it.