The sun has set by the time I park in Shafer, Minnesota, and the night is so still that you'd be mistaken for thinking no music was there at all. I can barely see what's ahead of me with each footfall, if not for the crunch of gravel beneath my feet, and the dim light of the sculpture garden lobby ahead. As I pass through the sliding doors and emerge through the other side of the building, into the sprawling field, the drone of the instruments finally takes shape. A small bonfire quietly kicks its embers into the darkness, as if spitting what it can out into the unyielding black. Beyond, discontinuous shots of nature are projected against a screen — first single images, and then split screens, before splintering into miniature grids, tableaus of greens and blues.

I spot the outlines of at least six people on the stage — among them, other Minnesota locals like bluegrass-folk guitarist Dave Simonett from Trampled By Turtles and ambient pop artist the Nunnery — and I can barely make out their faces from the shadows that the light casts. But Alan Sparhawk's figure is unmistakable — the way his shoulder-length curls drape his torso, the meditative stance he takes, hovering over the guitar effects pedals by his feet. There's a shrouded grace to the way he plays, merging into the periphery of his peers, no more prominent than anyone else performing. He becomes the hum of the evening — the soft buzz of insects, the silent flickers of verdant scenery on the screen behind him. He becomes what harmony emerges in the stillness, the music that can be wrested out of the darkest nights.

"I'm not mad at God," Sparhawk says. It's earlier the same day, and he sits on the other end of a Zoom call from his home in Duluth. The lighting is dim, letting only the soft whispers of morning sun seep in against the dark olive walls. Sparhawk stares offscreen, somewhere toward the corner of the room. In the pause, he deliberates over his next words, as if trying to explain a thought he's been chewing over. "But I am kind of curious," he continues, slower now, "where God is."

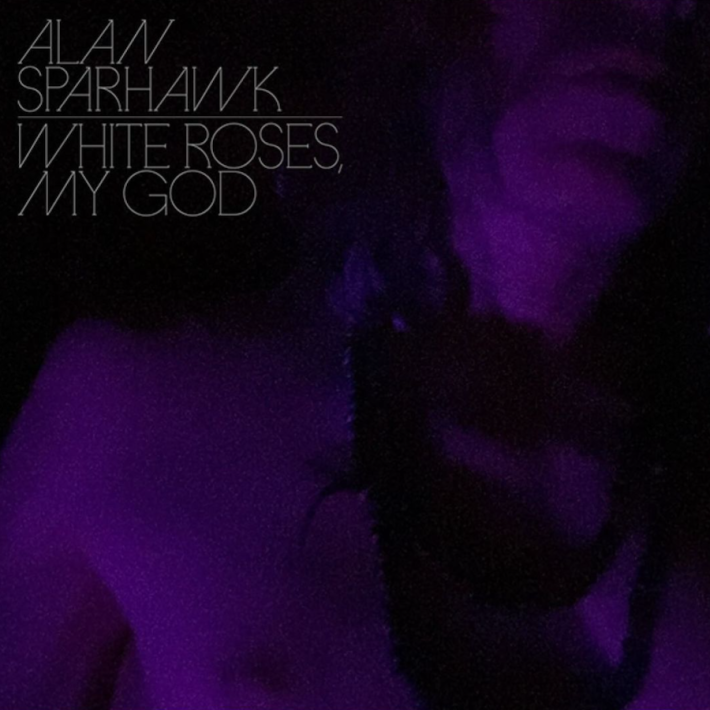

It's about 45 minutes into our call, and we're finding it's impossible to talk about the songwriter's new solo record White Roses, My God without talking about the grief that surrounds it. "I've never felt so much nothingness, so much emptiness," he says about the feeling. "It's weird, because it does make you question: ‘What was I feeling when I was feeling God before? What was I feeling when I was feeling the eternal nature of someone's soul?'" He stops again, his eyes cast upward. "And I'm not ruling out the possibility that, at some point, it'll kick in and I'll feel those feelings again, and I'll feel that presence, and I'll feel her presence even."

The lower part of his face twitches, his chin pressed against his palm, as he says, "It's been a shock. Maybe it's a test. Maybe this is just the next level of existence and spirituality that needs to be grappled with. But I'm not ashamed to say that it's definitely been a shock, and I'm looking at things a little harder now."

For three decades, Sparhawk and his wife Mimi Parker were the voices and souls behind Low. Sparhawk's guitar was patient and melancholic, but often holding the capacity for lacerated anguish, and Parker's drums were always the steady, measured beating heart of any given song. The group charted a seminal career that only seemed to further blossom, creatively and critically, as the years went on. Their early slowcore records like The Curtain Hits The Cast and Things We Lost In The Fire found the two stirring all the emotion that could be mustered out of stillness, while their later BJ Burton-produced releases like Double Negative and HEY WHAT wrenched the hurt and pain beneath their songwriting into noisy, harrowing pop songs, equal parts fraying and hopeful. But the change in direction, tragically, became a mirror for what was happening in the midst of HEY WHAT’s creation, as Parker passed away in 2022 at the age of 55 following a two-year battle with ovarian cancer.

The music that Sparhawk made following this loss takes on an entirely new form. Within the first moments of White Roses, My God, the difference is stark. Opener "Get Still" sets the scene with forlorn synthesizer loops and drum machines dominating the mix; when Sparhawk's voice finally comes in, it's pitch-shifted beyond recognition, his words only half-legible, often seemingly made up of stream-of-consciousness phrases or imagery. If the music of Low was about painting a feeling so vividly that you couldn't look away from it, White Roses, My God submerges you in the deep-sea depths of its emotions, a complete sensory embrace that swallows you whole as it works to make sense of the unimaginable.

For Sparhawk, the tracks just naturally "fell out." In the months following Parker's passing, he set up a space in his garage for his son Cyrus and his friends to mess around with a synthesizer, drum machine, and Helicon VoiceTone Correct pedal. "When the kids would use it, it would be pretty inspiring," Sparhawk says, in his warm baritone rumble. "I found myself messing around with those things too. I'm a constantly curious musician." In messing around with the setup, he became enamored with the idiosyncrasies of how the rigid parameters of the tech, such as locking a synthesizer's MIDI output to a drum machine and hard-pitching a vocal take to a specific key, jutted up against his own impulses and subjectivity. "You're getting this cross of human decision-making and input, but being facilitated by machines that are locked up and working together."

Deliberate attempts at turning these experiments into a full-fledged endeavor, let alone as a means to process his loss, were never the intended outcome. "I'd just sit down for an hour and improvise with the machines to see what would happen. And, sometimes," Sparhawk adds, gesticulating with his arms, "I'd feel some vocals inside me welling up. Something would click and inspire something spontaneous. The more I did that, the more I was able to just hang with it and try things. You spend 20 minutes poking around and not finding anything, and then suddenly, something would come together and something would come out of you." As songs and fragments began coming together, Sparhawk started showing what he had, first to Cyrus, and then to his fellow Duluth musician friend Nat Harvie, both of whom enthusiastically encouraged his pursuit of this new approach.

"I remember that feeling from writing for years," he adds. "You sit with a guitar and strum and mumble, and every once in a while, you'd step into something that has some life or spirit. Sometimes a phrase would come out of you, or sometimes it would inspire a whole song. This stuff was just different parameters from what I'm used to, and it took a while before I started looking at it as something valid at all."

Sparhawk's impulse to lean into what the voice pedal could do came from this same pull toward curiosity and experimentation. He picked up the Helicon pedal cheap, drawn to how radically unusual its possibilities for altering the human voice could be. (The press notes for White Roses, My God cite everything from the Camille alter ego of Prince, another Minnesotan, to the bracing pitch manipulation of 100 gecs.) "It's pretty intense after having so much time singing through a mic and hearing your voice," Sparhawk explains. "At least, for a while, every way I've made music and sung before is pretty loaded. It's really a shock and takes you aback when you sing into the mic and something else comes out, especially if it's something you still have some control over. There's something about having the pitch controlled — it forces you to only hit the right notes. When you take pitch accuracy off the table, it brings in a lot more room for texture."

In hindsight, though, the deeper implications of this choice aren't lost on Sparhawk. Though he wasn't consciously trying to "find a new voice," he says he recognizes the draw in speaking and expressing himself in a way that was alien from the methods so closely tied with his previous decades of material with Parker. "Grief makes you rethink everything. Sometimes, you'll look at something you've looked at your whole life, and suddenly it's changed now: 'I don't know if I want to hear that, I don't know if I want to make that sound anymore.' The part of me when I was young that wanted to be heard and understood has changed a bit, matured." It's palpable in the way the voice manipulation on the record obfuscates the sentiments at times, more often becoming about the sonic register and emotional timbre of a melody more than the legibility of the lyrics. On much of "Black Water," which sits at the midpoint of the record, Sparhawk's words sound more like rhythmic, harried exhalations.

On the impulse to make everything immediately understood (or go in the opposite direction entirely), Sparhawk says, "I've gone through some experiences that really changed my perspective about that. Thirty years of getting up on stage and talking about my feelings… I've gotten to explain myself. And, at a certain point, you go, 'What do I have to say, then? What's valid? What justifies me continuing to be this guy standing in front of people and singing to them?' But I've had some good friends reassure me and go, 'No, no, people want to hear your voice. Do your art.'"

Sparhawk lifts up his shoulders in a shrug, and says about the voice manipulation, "Maybe it made me excited to sing again." He softly chuckles — maybe at how straightforward the answer is, maybe at reliving some of the catharsis that this newfound approach brought him — and puts his hands to his head, tousling his own hair. "I found myself able to be a lot more free. Over time, you get hung up on what your voice is supposed to be saying. There's stuff on here that I would have never heard my own voice singing."

The introspective "Feel Something," one of the eventual centerpieces of White Roses, My God, became one of Sparhawk's first nudges toward what the record was rooting through. Over blips of synth notes, Sparhawk's pitch-shifted voice mutters, "Can you feel something here?" The track builds and the sentiment shifts, first into a longing for any kind of emotional response ("I want to feel something here"), and eventually a moment of breakthrough ("I think I feel something here"). "That first line came out of me, and it just kept coming and mutating," Sparhawk explains. "I was still only about seven or eight months into Mim passing away and…" Sparhawk stops. It's the first time either of us has said her name during the interview. Quietly, he resumes: "Yeah, ‘Feel Something' was one of the earlier ones that made me pay attention to what was going on."

In the months after Parker's passing, Sparhawk's most immediate network of musical friends and collaborators were the lines of support that kept him going. Be it former Low bassist Zak Sally, the members of Trampled By Turtles, or Cyrus and multi-instrumentalist Al Church — who formed Derecho Rhythm Section with Sparhawk in this period — anytime someone reached out and offered an escape in the form of music or a getaway, it proved to be a valuable lifeline for Sparhawk. "Music kind of became this next language, this common ground," he says. "I know that's cliche, but it really is something, when you can coexist and hang with someone and interact on a musical level. Sometimes, that's everything. Especially when you're at a point where you're not gonna be able to fully verbalize. Maybe that conversation isn't gonna happen for a while. But, with music, you're together. You're speaking. It flows. There's no obligation. There's no pressure for it to be coherent. You're not having to be conscious and linear."

"When people are grieving," he explains, "at least for me, there's this part of you that's like, 'I really wish I could say something.' You want to help, but there's really not much advice for anybody going through that, other than being there for them." He mentions what it feels like to lose someone who becomes a crucial part of your daily way of living, and how their absence can then completely disrupt your basic patterns of human behavior. "You'll sit there and see this task in front of you that you need to do, and you know what you need to do, and you just can't do it. And it took me a long time to realize that it's because I'm used to having in the back of my brain that this person is over here and they'll come in and check to make sure I'm doing that right."

For as much time as we spend during the interview talking about Sparhawk as a musician, there's just as much time spent on how complex, arduous, and all-consuming the grieving process can be. Parker was more than a wife, and more than a bandmate — she was a life partner for most of her and Sparhawk's lives. Sparhawk and Parker first met as children, and their connection at a young age was so strong that they began dating as teenagers, sparking a relationship and marriage that would continue for all the decades to follow.

Whenever our conversation drifts into what Parker meant to him and the devastation of losing her, it's clear just how much Sparhawk is still emotionally grappling with the magnitude of her passing, of losing someone who was by his side longer and closer than anyone else. "It's a very chaotic process, absorbing and processing that," he says. "My father passed away six or seven years ago, and I remember that feeling and the chaos of that. I have to say, it really prepared me for a much closer and more unexpected loss." He goes quiet for a moment, and then begins again, with greater gravity to his voice than before: "I would've been really taken aback if this was the first time I lost someone and experienced that chaos. There's nothing like losing someone that's close to you — it'll change your perspective forever."

In Sparhawk's words on loss and grief, I feel a truth that's become all too familiar to me in the weeks leading up to our interview. In the middle of August, I was shaken by the sudden loss of my close friend Piper — a passionate photographer, an occasional lover, and a tremendous pillar of support in the all-too-brief time I knew her. In the initial days, the reality and permanence of her absence settled in with a suffocating weight, and the feeling became all I could think about, an enveloping physiological reckoning.

No more than three days later, the advance for White Roses, My God arrived in my inbox, and I found I could not listen to it without recognizing grief in every corner of the record. It was there in the most direct of places, and it was there in even the most abstract of connections. It was everything I found myself going through in the rawest, most immediate moments: immense sorrow; an outpouring of love; doing anything but confronting the matter; running straight toward it at a full sprint. The record arrives just when I can read its most obfuscated sentiments with the most piercing clarity imaginable.

That's the thing about grief, as Sparhawk and I find ourselves discussing: It's every emotion, but pitched at such extremes and with such jarring fluctuation that it can prove completely unpredictable. We talk about the loaded trap of being asked, "How are you doing?" in the midst of grief: "'Now?'" Sparhawk imitates a hypothetical honest response, to give an example of what the progression has been like for him. "'I don't feel a fucking thing. Right now, I'm numb. In 15 minutes, I'm gonna feel things that I cannot even begin to describe to you. So… what the fuck is this question?'"

But, just as quickly, he is able to recognize the perspective that the past years have given him — namely, in being able to more generously understand people's reactions, especially in moments of extreme duress. "Some people want to be close to grief," he continues. "They want to be around it. Some people run away and they don't know what to say. I was one of them. I'd always be hard on myself about that. But after experiencing that, it's like you can forgive yourself. Because there isn't anything you can say. I understand that reaction now. I guess that's one of the graces of loss. You realize that inner process from moment to moment — one hour to another, even — is a wildly different place."

He brings up his own fraught history with depression, and how he worried its past grip on him might make him emotionally unable to handle Parker's passing. "With depression, it's weird because you feel like shit, and everything around you feels like shit. There's this dissonance. Everything around you that originally brought joy is gonna feel like crap. And it's the confusion that eats you up. It's the confusion that changes your perspective about things and makes you question things and makes you hate yourself."

"But, man, when something real happens, it's so real. And you can't do anything about it." He pauses, looking off to another wall of the room. "It's not your fault, clearly. There's something almost refreshing about knowing why you feel like shit. If you know what it is, you can sit with it. You can come to terms with it." He sits back in his chair, retreating further from the camera, crossing his arms. Half a minute passes by as he reflects on what he's said. "In some ways, I feel like I'm doing okay, because I'm not confused about why I feel so empty."

Our conversation drifts to "Heaven," the shortest track on White Roses, My God, and by far the most unflinching. Where most other lyrics are shrouded in vocal effects and arrays of synths, Sparhawk follows a simple melody, his voice pitch-altered, but clear as on any Low record, as he sings, "Heaven/ It's a lonely place if you're alone/ I wanna be there with the people that I love/ Maybe someone that you're waiting/ Oh, who who's gonna be there?" A few layers of choral vocals swell, and then the track ends, just over a minute after it had begun.

It's the track that snuck up on Sparhawk's creative process the most suddenly, and it's here where the emptiness Sparhawk speaks about has come to a head with his lifelong religious beliefs. He and Parker both belong to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which instilled a strong security in the conviction of life and family being eternal: "It brought perspective that got us through hard things. It made us closer. It made us more hopeful." But he's forthright about the ways Parker's death has made him question these notions.

"You know someone and they're more real than anything else you can look at or put your hand on — they're more real than these chairs," he says, nodding toward furniture on the other side of his camera. "I could shred this chair into toothpicks, and then crush those toothpicks into fiber, and crush that fiber into the molecules. I could break it down chemically to the parts that went into making the wood, and it would still be material. It would separate into the elements. Nothing is created or destroyed in the universe. But when someone dies, man…" The words escape him for a moment. "...And they're gone," he stammers out. "It's a loss, for sure. Something that's so a part of your being is gone. Just the feeling of something being gone is really striking."

With consternation, his speech becomes slower, more uncertain. "I have to admit, I'm still a little bit puzzled," he continues, "and wondering how that sits with the concept of eternal life and God. It's very possible that what I thought all my life is maybe a little different. If there is nothing there…" He stops there, and his expression speaks volumes to his doubt before any other words. "That's quite a thing to take in for someone who's believed his whole life."

Sparhawk hopes, though, that his spiritual trials don't discourage Low listeners who found meaning in the band's openness when it came to faith, both in lyrics and direct statements beyond the records. But, significantly, he recognizes that his belief system imparted on him and Parker a way of living that put interpersonal bonds and fulfillment through family above all else. "I know that being married and being together and working hard on something, even having a family — the potential of helping each other be better people… Yeah, that's real. I'll take that." His voice rushes with the most certainty of anything he's said the entire call. "If that's God, then that's God. And, if it's just what humans are possible [of doing], then I assure you that's the best thing we can do: figure out how to love each other, figure out how to accommodate, how to be forgiving, patient, and how to give up enough of yourself to want trust. That was something Mim was saying toward the end: ‘Love is the most important thing.' If God is love, then there is a God, because love is real, and I know that."

Toward the end of the call, our last point of conversation is on "Project 4 Ever" — the slow-burning expansive thrum that closes White Roses, My God, and the most emotionally difficult one for Sparhawk to talk about. He begins by mentioning his unequivocal knowledge that it had to be the last song on the record, and starts talking about the song being a means of embracing, before he stops himself. A tear glides down his face. His voice trembles, as he says, "The song feels to me like it's sort of the end, and what it's doing is taking everything — all the different angles, tears, ecstasies, and chaos in the record — and embracing it in one place. It doesn't answer the question. It doesn't solve anything. It just embraces it, and opens the door to the future, the next moment. That song feels to me like it's a little bit of 'I don't know,' but I'm embracing it anyway."

The word "forever" is an especially meaningful thing for Sparhawk, as it was for Parker too. He talks about a guitar he played for years with Low, one with a small sticker that says "forever" affixed, unable to speak about it without crying. "It's always just a reminder to me — perspective of life being forever and love being forever. There's something about that that cuts through everything else and, in a way, answers and resolves the confusion, the question of ‘What are we going to do now?' The answer is: ‘We don't know.'"

His understanding of eternal life isn't in anything tangible, though he expresses gratitude for how Parker lives on forever in the recordings she made over the decades. ("Isn't that crazy?" Sparhawk says, with a tearful laugh. "That's forever.") It's in the place a person holds in others' hearts, even long after they have gone. It's the eternal, cherished memories that can never be destroyed, only created. "It comes from living," Sparhawk says, "and I think it's because life is beautiful. A human being is more than a chair. The best we can do is look at our lives and [think], ‘As a living person, what am I doing that's of value? What will be of benefit to someone else after I'm gone? How can I still live in the heart of those that I love?'"

In the days after the interview, I sit with Sparhawk's words, and his perspective on grief as he has sat with it over time. At a benefit show in her memory, I get Piper's graffiti tag — the word "joy" in her handwriting, with a smile tucked inside the "o" — tattooed to my chest. It will keep her, and all the memories of the happiness she gave me, living in my heart, as literally as that can ever be.

At the end of our call, Sparhawk invites me to the drone performance that evening — a fitting gesture to echo what he took comfort in. In its final moments, the group's hum grows so quiet in the newborn night that their silences become the sound. The ambience becomes the melody, the melody becomes the ambience. For one of the first times since August, I feel a stillness and peace that I had forgotten I could feel. The last note rings out so softly that it's hard to tell when it fully fades to a distant echo. If you listen closely, you can hear the music you need, wherever you need it most.

White Roses, My God is out now on Sub Pop.