We’ve Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

Every new Bonnie "Prince" Billy record comes with a twist. For The Purple Bird, released last week on No Quarter, the variable was this: Will Oldham, inscrutable legend of New Weird Americana, wrote and recorded with old-school Nashville country music pros, under the guidance of grizzled veteran David "Ferg" Ferguson, who's become a treasured friend, collaborator, and group-chat co-conspirator since they first met working on Johnny Cash's American series decades ago. It's only the second time Oldham has ever made an album with an official producer in tow.

The result is a set of smart, funny, emotionally charged songs that feels like a highlight in a catalog without many lowlights. "Tonight With The Dogs I'm Sleeping" marries a clever lyrical conceit ("I'm all bark and she's all bite/ I'm sleepin' with the dogs tonight") to a graceful honky-tonk groove. The gorgeous, dusk-tinted ballad "Boise, Idaho" puts a much sadder spin on romantic discord. Meanwhile the polka "Guns Are For Cowards" takes serious business to comical extremes, asking the listener what kind of violence they'd enact if they knew they could get away with it: "Who would you shoot in the face?/ Who would you shoot in the brain?/ Who would you shoot in the back/ And leave bleeding out in the rain?" Legends like John Anderson and Tim O'Brien are in the mix, too. It's a fantastic album, and I'm not sure anyone could situate it Oldham's career as well as the man himself did when The Purple Bird was announced:

I’ve made records with friends, collaborative records like The Brave And The Bold with Tortoise; the two Superwolf records with Matt Sweeney; The Wonder Show Of The World with Emmett Kelly; Get On Jolly with Mick Turner. These collaborators get top billing because that’s how this business works. This record, The Purple Bird, is similarly a collaborative effort but the collaborator is the producer, David Ferguson. He’s a giant of a man, an epic musical force, a dear friend. Our work together on this record was the result of years of sharing hard times and great joys, songs and stories, of making music together and apart. There's a lot of trust in this record on Ferg’s part and on mine, and the trust was hard- and well-earned. When I listen to the record, oftentimes I can't help but laugh in wonder that life allowed me to participate in such a thing.

Life has allowed Oldham to participate in so many things. The Louisville native boasts one of the most fascinating careers in music history, bringing haunting off-kilter gravitas to masterworks like I See A Darkness and Superwolf while working with a staggering range of luminaries. The former child actor's journey has also involved roles in acclaimed indie films like Junebug and Old Joy; he even snapped the iconic cover art for his close friends Slint's landmark Spiderland.

I could spend days asking him about all his endeavors. Back in December, Oldham and I hopped on a video chat to discuss The Purple Bird, Caveh Zahedi, Joanna Newsom, Jason Molina, covering the Ramones with David Berman, covering Billie Eilish with Bill Callahan, working with David Byrne on Sean Penn's goth-rock Nazi-hunter movie, how he ended up in Jackass 3D and a Kanye West video with Zack Galifianakis, and much more.

The Purple Bird (2025)

You've talked a lot about your relationship with Ferg and what an important friend and collaborator he is in your life. You guys have done a fair amount of work together already, but how did this project specifically come about? Who asked who? Or is it something that just kind of happened?

WILL OLDHAM: It really is something that completely happened. Like the whole thing was a complete and wonderful surprise, and I tried to share that idea with the cover. The cover is this painting of a purple bird that's that's derived from a drawing that Ferg had made when he was a child, and I asked Lori Damiano to do a version of Ferg's purple bird and then depict me sort of in shock and awe and wonder at this massive crazy beast because that's sort of how I felt all along.

I had just called Ferg a year and a half ago or so and hadn't seen him in a little bit. And I just said, "I wanna come down and see you." And he said, "OK, well, why don't I set up a songwriting session for us?" And I was like, "Whatever you need to do, I just want to come down and hang out." And he's like, "Yeah, I'll set something up with Pat McLaughlin," who I've met many times with Ferg, who's a wonderful guy. I love seeing him, spending time with him. And so that was thrilling. And he said, "Yeah, maybe I'll see if Tim O'Brien is around. Or Roger Cook, he'd be fun to write a song with." I said, "Yeah, sure," and literally just went.

I think Ferg had thought that I had done songwriting sessions before. I think it's a super common normal practice in Nashville: If you're a songwriter, you do these things. Like, you make an appointment and write a song.

So I drove down there and spent a couple of days doing these things, and they were very productive and incredibly fun. I think everybody was having a good time. And Ferg suggested that we do it again. So we did it again, and he started to say, "Maybe we'll do a couple more of these and then we'll cut some demos," I guess maybe with the idea that we would send some songs to other performers and maybe they would — you know, we'd be pitching ourselves as songwriters for other people.

Every time we had one of these sessions, we came out with something that we were really into. And after the second trip, he said, "How about we do one more of these trips and then we maybe book a recording session?" I was so scared because the world is so fucked up, you know? We had a bird in the hand. I was like, "Let's not wait. Let's just go ahead and schedule a session, and I can come up with odds and ends to flesh out a record's worth of material. And he just said, "OK." But literally, I was in the middle of the early stages of creating a record that I just pushed aside once this momentum — it was a complete surprise. It just started happening.

And Ferg, he brought out the big guns. Like he brought the best songwriters he had access to, which happened to be probably some of the best songwriters working in Nashville and most experienced, as well as what he called the best band available in Nashville. And I don't think that that's an exaggeration in terms of these people's experience. Everybody began their musical careers in a pre-digital world. And so we could make a record in what is effectively the most rewarding way of making a record, which is to not count on modern technical marvels of digital recording, just not even think about that stuff and just think, "Well, I'm gonna bring everything I can to the table so that we can make the best record we can possibly make, and that's what we'll have to work with." And everybody in the room was that way.

There's, I'm sure, a countless number of brilliant, uniquely talented younger musicians working in Nashville right now, but you're always gonna have this subtext with everybody about things like tuning and editing and comping that these guys are like, "Well, we could do that if you want to, but why don't we just do it right the first time?" And Ferg had access to a group of people who think like that. And that's how I've always liked to think. I like the idea of just bringing your game to a recording session, and then that makes a powerful record that's full of complexities that are interesting to listen to. It's not interesting to listen to a record that has been digitally manipulated into quote-unquote perfection. It just gets tedious and fatiguing on the ears, I find. You want to have a complex experience where your brain can divert itself into various aspects of of the performances and of the songs.

You mentioned the Ferg's childhood drawing. How did that become the conceptual binding for the project?

OLDHAM: It's just so outrageously outside of what Ferg kind of consciously presents as a human being. But then it's interesting because the only reason I know the drawing is because he fucking hung it on the wall of the mother-in-law apartment where he decorated for his friends and colleagues to stay in when they come to visit him. The only thing I ever asked Ferg about that picture was, "Ferg, is it OK if I call this record The Purple Bird?" That's the only question I've ever asked him related to that. It's just that somebody — was it his teacher? Was it his mother? Was it him? — framed it and put it behind glass in the first place and kept it from second grade. And so I'm just like, "OK, this is some weird beautiful" — because he's ornery and he's gruff. So where does a gruff and ornery person get off hanging up a childhood drawing of a purple bird that they made in second grade? And to me it was kind of like, well, this is part of the mysterious enigmatic beauty of the human being that is David Ferguson.

My favorite song on the album is "Boise, Idaho," and I was wondering if you could tell me how that story came together.

OLDHAM: Yes, that was the first [day]. I drove down on, I think, a Wednesday morning from Louisville to Nashville for a 10 o'clock appointment at Ferg's with Pat McLaughlin and Ferg. So we did it in the apartment. And as these things go, or as a Nashville recording session goes, they open up with 15 minutes of bullshitting. And then eventually work begins. But the songwriting work is different from recording work. Because recording work, it's really obvious when it started becausesomeone pushes record. And in songwriting, at least in my experience with these people, it just — everybody has a guitar and eventually somehow the conversation evolves into songwriting process.

One wonderful and memorable experience Ferg and I had, there was a tour we did maybe 10 years ago, and it was Ferg and Sweeney and me. And Ferg opened for me and Matt, but we would sing a couple of songs in Ferg's set. And I think my cousin George came along as a roadie and our friend Oscar came along selling merch. We started in a cave in Texas and made our way up. Our last show was in Anacortes at a festival that Phil Elverum and his late wife had put together. And in the middle of it was Boise. And Boise was a wild insane time where I think everybody but me kind of had an adventure. And so we were just talking and laughing about that, I think, and then the song just sort of — I mean, have you seen My Neighbor Totoro?

I haven't. With a lot of animation, I haven't really delved into it that much.

OLDHAM: I do because I have a child. I'd heard about My Neighbor Totoro. It had never interested me. And then with a child, now I've watched it 20, 30 times or something like that. But there's a scene in it where the kids plant some seeds in their garden, and then they go to bed, and then they dream — or don't dream, it's sort of Wizard Of Oz-y — that this Totoro monster comes. And they have this ritual around the garden, and the plants grow. And they not only grow, they become these massive camper trees, these huge, huge trees. And in the morning they wake up and the plants have indeed sprouted.

And that's like what these songwriting sessions are like. Are they real? Are they not real? Where's the song come from? Every once in a while I could get a foothold and push it to, "OK, let's focus on the bridge right now. And who is this person singing, and how much self-doubt should be expressed?" But we just latched on to Boise as a, as an anchor image because we had talked about it with weight and gravity in a conversation that led to the beginning of the creation of the song.

And that's the only song also that any contribution from one of the co-songwriters came after the session. Everybody pretty much put their stamp on it and walked away except Pat. In the weeks leading up to the [recording] session, he called and said, "Willie, got this chord I think we should use. " I don't know the formal names of certain chords. It's basically like if you strum an acoustic guitar that's traditionally tuned and don't put your fingers on the fretboard at all. It's just the open sound. It's used at the beginning of two different Jimmy Webb songs, "Wichita Lineman" and "Galveston." And since "Galveston" and "Wichita Lineman," of course, are both geographically linked songs — you know, they have a city in the fucking title — I think Pat thought, Jimmy Webb started those songs with this obtuse chord, let's try putting that into "Boise."

This album is coming out on No Quarter. It's kind of a rarity for you not to release through Drag City. What was behind that decision?

OLDHAM: There has been a couple, like I See Darkness and Ease Down The Road, most specifically, but also the Bonnie "Prince" Billy self-titled record from 2015 or something like that, that I just released myself and distributed myself and everything. I have a deep, long, wonderful, complicated, mostly incredible relationship with Drag City, and each time I've stepped away with a record, there's been some significant reasons. And they are generally difficult and complicated and painful. And so I don't know exactly how to talk about it, except to say that at this moment in our lives, there was a practice embraced that I needed distance from. It came — I think the record was almost done. The only thing that hadn't been done was John Anderson singing and then the final mixing of that song, "Downstream," when I realized that this is how it was gonna go. I wasn't sure what to do with the record. And fortunately, of course, I'd had such a wonderful experience in the past couple of yearsdoing records with Mike Quinn and No Quarter. I'm gonna have some kind of relationship with Drag City for the rest of my life and who knows what it will be. But for the moment, I'm exploring things with No Quarter.

Dropping Acid In The Documentary Tripping With Caveh (2004)

When Caveh Zahedi approached you about doing this movie, were you already pretty well experienced with those kind of drugs? Was that your first time? What kind of context were you bringing into it?

OLDHAM: It wasn't my first time. It's something that I've never deeply, deeply embraced, but always had a profound interest in and respect for. I think the first time I remember was actually in Chicago before, I think, I started making any music. And it was with, I think, like David Grubbs, David Pajo, they were there. I remember Grubbs telling me like, "Don't worry, you know, it'll take 30 to 40 minutes to kick in and it'll be fun." And I'm talking to him and I'm feeling, 10 minutes in, like I'm experiencing a consciousness that I had never experienced before. And then of course was immediately shitting and vomiting and then tripping balls by before that 30 minute mark that he promised me. It was the easy entry. But it was great. We had a lot of fun.

I think that Caveh's motivations in creating things is very different from mine, but I have a guarded respect for it. More recently, he's got a Getting High With Caveh thing now, maybe a YouTube series or something like that, and he came here to Kentucky this year and we shot one of those that he's gonna edit together and put out. He said it would probably take him about a year to edit it.

I appreciated how committed he was to his art and figured it would be a learning experience to dive in with somebody who is so all in.

Do you know why he asked you? Did he tell you?

OLDHAM: I think we had a little bit of a communication leading up to there. Most of his films are documentary, and I think he had shot a scene in which a song of mine was playing, and so I think he first reached out to just get permission to use the song. And I think the communication around that evolved into something that he found compelling.

"September 11, 2001" With Jason Molina & Alasdair Roberts (2001)

Was that something that was written on the spot in response to what had happened that day?

OLDHAM: Yeah, oh yeah. We were together in Shelbyville, Kentucky, in this farmhouse where my younger brother lived and ran a recording studio for a few years, and we'd come together. They had asked if I was potentially interested in making a record because they were both tired of being compared to me by press. And they were like, "We don't think that there's any similarity," and I was like, "Yeah, I don't either." And they're like, "Let's make a record together, and then people will see."

And then we did that record with Galaxia. That was a record label run by my friend Thomas Campbell, who's a surfer and visual artist and filmmaker. And so we just happened to be there in September of 2001. I remember the first person I heard about anything happening was Jason Molina, who I already knew at that time to be a compulsive, wildly pathological liar. And so when I hear him say, "Oh, something's just happened," I'm just like, yeah, the boy who cried wolf. And then I heard the phone ring in my brother's room, and he answered the phone and he was like, "Oh my God," and I was like, oh, maybe there's something to what what Jason said. And then we were in the middle of a three or four-day session to make this EP, which is called the Amalgamated Sons Of Rest.

I have all different kinds of complex mixed feelings in general about Jason Molina and his work, but that was his song, his improvisation. And he could be such a brilliant performer and improvisational lyricist, at that time especially, where you just didn't know where things were gonna go, but you knew he was gonna push you out into this marvelous uncharted territory, oftentimes daunting and frightening. And that's where that went, and that's where it came from.

Getting Slapped By Chris Pontius In A Gorilla Suit In Jackass 3D

You played an animal trainer whose gorilla escapes. Did Chris Pontius actually slap you in the face for that scene?

OLDHAM: Yeah, I saw stars for a moment and was out of consciousness for just probably five to 10 seconds. And there was a significant knot on my head because in order to extend his arms into gorilla arms, there were these elaborate gloves, each one was about 13 or 14 inches long. And his hands fit into the gloves, and they were hefty things. And he swung and, yeah, just knocked me.

Have you known the Jackass guys for a long time? How did you end up in the movie?

OLDHAM: I knew Lance Bangs, who's been associated, of course. And he'd been a fan. I sort of knew him, and we communicated about a variety of things. And then I think at one point he was working on the Slint documentary, and I asked him what else he was working on. And he said he was working on a new Jackass movie. And my dad was dead at that point, but I had kind of a bonding thing with him over Jackass. And so I was like, "Is there any way I can get into this Jackass thing?" And he said, "Yeah, if you write me a theme song." I was like, "For what?" "Write a theme song for my life." So I wrote and recorded Lance a theme song for his life. And then a few days after I sent it to him, I get this phone call like, "Is this Will?" I was like, "Yeah." He's like, "This is Knoxville. I hear you want to be in Jackass." And, yeah, I was like, "Yes, of course I do, I absolutely do."

That's awesome. Has your theme song ever been released to the public?

OLDHAM: [laughs] I don't think so, no.

He's just keeping that one for himself.

OLDHAM: I tried to pattern it after a Saturday morning cartoon song from my childhood.

Covering The Ramones' "Outsider" With David Berman (2016)

What were the circumstances of making that?

OLDHAM: So I have this long working relationship with Mark Nevers. And I met Mark Nevers through David Berman back in 2003, '04. I was trying to make the record that ended up being Master And Everyone. And we're trying to make it at my brother's studio, and things weren't jelling in good ways, and I remember David talking really positively about his experiences in Nashville with Nevers. And so I asked David to introduce me to Mark. He did, and we made a bunch of records together.

And Marky's a big Ramones fan, and I'm kind of a lifelong Ramones fan, worshipping definitely at the temple of certain Ramones records for the rest of my life, I'm sure. And so we had talked about maybe one day making a full Ramones record with Marky. And then Marky called and said, "That's it. I'm out of here. I'm leaving Nashville. Priced out. They've rezoned my neighborhood so we can't record here anymore because nobody wants to hear music coming out of my house." And so he moved to Pawley's Island, SC. But he's like, "You want to come down just for fun, do one last session?"

And so I brought two songs, and then I was like, "Well, why don't we just do a Ramones song since we've always wanted to?" And one of the great parts of many earlier Ramones songs, one on each record would be the Dee Dee break. Dee Dee would take over the vocals. And the song "Outsider" has always been one of my favorite songs from Subterranean Jungle. And I was just like, "Who's gonna be Dee Dee? Who's gonna be Dee Dee?" And we asked David if he would.

We released the 7" of the other two originals on a German label. And then that song has just been sitting around, and it was just like, "Let's put this song out."

You did that show this year with Cassie [Berman] and Silver Jews. I was really jealous to miss that. It looked like a very special time.

OLDHAM: It was very special. It was really nice, yeah. And I think that I've heard that they're gonna do maybe some more shows as that band, so hopefully that's true. It's a great group of people.

Back when they were touring in the 2000s, when they were in Columbus, they played at this elementary school that I think had been a gymnasium that was converted into a music venue for three months. It was really great despite, or because of, the bizarre environment.

OLDHAM: It sounds like a great environment. I always relish the opportunity to play in spaces that are considered atypical spaces that are charged with the ghosts of past intention or lives lived. Playing in prisons, hospitals, schools, why not? They should just be happening all the time. Bars are relatively unremarkable spaces, once you played a couple 1,000 of them.

Voicing The Character "Will" In Video Game Kentucky Route Zero (2014)

Have you played the game? Does the character look like you?

OLDHAM: I have no idea. I think I tried to play it for a moment and... I have an affection — well, I don't even know what you'd call it. I have a relationship with video games, but I'm definitely in a dry spell right now.

But no, it was just the quality of the communication when they reached out, and then what they were asking. They described it, and I just treated it more like voicing an animated character in a cartoon or an acting role, I guess. And I've gotten such terrific feedback over the years from the freaks who are aware of that game and then who further have made the connection that that was my voice in there. It's the gratitude that comes from those people, I think probably because if we disappear into video games, there's a great deal of guilt in some of us when we disappear into a video game as a player. And so to have some sort of lifeline saying, "Oh, we didn't disappear into it, we're actually still connected to a shared reality with other people," is rare and rewarding. I think when people are like, "Oh, I know that voice! I'm not a crazy weird pervert lonely person spending hours by myself with my TV and video game interface!"

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

Sending Joanna Newsom's Demo To Drag City (2003)

How did you first encounter her and her music?

OLDHAM: It was 2002 maybe. We did a tour of the West Coast that was spurred on by a band called Rainywood, which morphed into Brightblack Morning Light. And we did three annual tours together. The first one was the West Coast. And in putting my band together, I think I was talking to Kyle Field of Little Wings and I think we figured out we were gonna rehearse in Portland, Oregon, and I asked if he knew of a keyboard player. And he referred me to his friend Rob Kieswetter, who records under the name Bobby Birdman. And he's from Nevada City, Grass Valley area.

And so we finished the tour. Last show was in Solana Beach, California, close to San Diego. And all the musicians dispersed except for me, Colin Gagon, and Rob Kieswetter, and we had to return all the gear to Isaac Brock from Modest Mouse. We borrowed a bunch of gear from him. And on the way, Rob was like, "Why don't we stop in Nevada City and play a show? There's a movie theater there. I can just set something up." So we went, and I remember seeing this young woman walking around, and she definitely had an interesting air about her, but I didn't meet her.

In the van the next day, Rob said, "Oh, my friend Joanna gave me her CD-R, and she wanted you to hear it. I think it's pretty good if you want to listen to it." And yeah, I thought it was incredibly novel and compelling and interesting. And for the next tour with Rainywood — I can't remember if they were Brightblack yet or not; we basically just moved one set of states over for the next summer — I asked her if she would open four or five shows. So we began just south of Solana Beach in San Diego the next year and then went into Arizona, New Mexico, Utah. And she played a handful of those shows, as did Dawn McCarthy.

I would often talk to Drag City about artists that I thought they might be interested in releasing, some of which they would not, and so that's when I created a, you know, a sub-label Palace Records imprint to put things out like Alasdair Roberts' Appendix Out project or Dave Pajo's M. It was first called M before it was Papa M or Aerial M. But Drag City, for some reason, they liked the Joanna Newsom. And now we're in the quandary we're in today with her.

What's the quandary?

OLDHAM: I'm kind of joking, but I've also just always been like — well, I don't know. Is she making music? I don't know.

Oh, that quandary.

OLDHAM: Yeah, I mean, part of it is I appreciate artists who have a respectful relationship with their audience, and I'm not sure that's evident there. But her husband makes a lot of money, so she doesn't have to worry about it. Maybe if my wife made a lot of money, I would disappear and have children.

Teaming With David Byrne And Michael Brunnock As The Pieces Of Shit For Sean Penn Movie This Must Be The Place (2011)

You were the lyricist for this. Were you given any sort of prompt for what kind of lyrics you should be writing? How did that work?

OLDHAM: Yeah, so the the the movie is called This Must Be The Place, named after that unfortunate Talking Heads song. And David Byrne was invited, I think, to score and write the songs for the movie. So he reached out to me — I don't know how he got my information — and he said, "I've been given a script. I'm supposed to write songs for this band called the Pieces Of Shit, and in the script it says that they sound like Bonnie 'Prince' Billy." And he's like, "Do you want to write those songs?" And I said, "Well, you got hired to write the songs. So what if we collaborated on them?" And he's like, "OK."

So he started just sending me demos in which he was singing nonsense, as is his wont. No, but he was literally singing nonsense, sometimes nonsense syllables and things like that. And then he would send me a vocal-free backing track. And so then it was just about writing songs, imagining that they were real songs — which, they kind of ended up becoming real songs.

I just finally watched the movie a couple of months ago for the first time all the way through. Because like at the last second, when the deal was being done, they said, "Oh, we also want to use this Bonnie 'Prince' Billy song called 'Lay And Love.'" And and at the time I was very against sync-licensing songs. But this was such a strange and unique project, I didn't want to fuck it up. So I'm like, "You know, OK, that's fine." Usually I say, "Let me see how you're using it," but I didn't do any of that.

And so then when the movie came out, I saw it. And the "Lay And Love" song comes in within the first 10 minutes or so, and I'm like, "Oh fuck, what did I do? I made a big mistake." And I just shut down, and I couldn't watch the rest of the movie, even as I thought Sean Penn was demonstrating a pretty brilliant performance, as well as Frances McDormand. But only a couple of months ago, I was like, "I should watch that movie." It's a really weird movie, but they're so good in it. Like Francis McDormand and Sean Penn are so amazing in that movie.

I have not seen it.

OLDHAM: Oh, it's worth it. It's never boring. It's ultimately kind of unsuccessful. It's got this weird Nazi hunter that Judd Hirsch does, and Judd Hirsch is surprisingly not that great in that, even as he was great in, like, Uncut Gems, for example. But the worst part of the whole movie is the last like three minutes, and you're just like, "Really?All this for that?" But Sean Penn is so good, and you've never seen him like that, or anybody really perform like that, I would say.

You mentioned you used to be against licensing songs. You had some interview comments many years ago about Wes Anderson and criticizing his approach to that. A, do you still feel that way about his approach? And B, you said you used to feel that way about licensing songs. Has your stance on that changed?

OLDHAM: Well, you know, everything has changed in this world, including Wes Anderson's use of music. He may or may not still work with Randall Poster, the music supervisor who had a big effect on a lot of movies at the time that Wes Anderson was really finding his feet as a filmmaker.

Part of it was sour grapes, because since I was a kid, a huge part of my life is going to the movies and also listening to records. And I found that the style of intersection that Randy Poster practiced was one that I just could not appreciate at all. Because what are you doing at the moment that that happens when you're watching a movie?For me, I start listening to the song, and I exit the movie. Because the song was not made for that movie, and oftentimes I would have a previous emotional association with it.

Like, I think another Randy Poster movie was The Squid And The Whale. Lou Reed's "Street Hassle" is in that. And Lou Reed's "Street Hassle" I've listened to countless times since I was probably 13 or 14, and it's part of my life. And so I'm just like, "What is my life doing in this weird Noah Baumbach movie?" And so for the seven minutes that that long, beautiful song is there, I missed the movie. And I'm just like, "Why did you do that?" And also, "Why did you not just give that as a springboard to a currently functioning music person and say..." You know, why don't you show the movie the respect, the audience the respect, the musicians the respect to make new music for your movie rather than just like, [adopts nasal nerd voice] "Ah this is in my record collection, it's a great song. I wish I could make a scene that had this emotional effect that this song has. I know what I'll do! I'll just use the song!"

That was one objection. The other objection was from the side of being song maker, at the time I was making a living off of record sales. And when I buy a record, I'm spending anywhere between, depending if it's a used cut out copy, anywhere between $3 and maximum $35, $40. But it's money! You know, I've gone to a store, I made a decision. I gave money. I've entered into a contract with that person. It's sort of like strip mining in Kentucky, where someone will say, "OK, I've sold you a house, but not the mineral rights to the house, and we can dig out from under your house and destroy the whole environment." And it's just like, I'm not gonna sell somebody a song on a record and then be like, and now I'm gonna sell it for more money to somebody else for a completely different use, destroying the context that you've created and the emotional connection that ideally I hope that you've created with this piece of music.

And now nobody's buying records anymore, so that contract doesn't exist, for one. I'm not hungry to license songs, but I would feel different about it. I've always said, like, "Let me see the scene, maybe it'll work." Usually it's no. And now I'm a little less adamant because, like, you're using fucking Spotify, so I really don't care if you have issues with me using this song because you don't respect the fact that musicians need to make a living. And at least these movie people are gonna throw me a few grand to use the song for a couple of minutes in their movie.

Covering Billie Eilish's "Wish You Were Gay" With Bill Callahan & Sean O'Hagan (2020)

You did all those covers with Bill Callahan. What about this song stood out to you guys as, like, "We should cover this."

OLDHAM: We divided the songs into — let's see, originally there were 18 songs. We're supposed to come up with nine songs, bring the nine songs to the table, and the categories were I had to come up with three songs that I wanted to sing, three songs I wanted to hear Bill sing, and three songs I wanted to do as a duet. At the time in our house, we were listening to that Billie Eilish record. It's mysterious and compelling — her talent, her ability, the way she and her brother worked.And she's a really, really good singer, and the songs are interesting.

In general, approaching covers for me has always been about exploring the mysteries of the origins of that song, everything about it. And if you cover a song and then have to interpret it for presentation to an audience or other musicians, it just goes a long way towards attempting to understand. You know, you can never understand it, but you can attempt to understand it.

So the idea was also just wanting to do a duet. One of my favorite moments with Bill came from the '90s. We were on tour together, and we were sitting in a motel before we had cell phones, talking to the Drag City home office. And I think Dan Koretzky asked Callahan, "So how's the tour going? Are you getting along with Will?" And I'm across the room, but I could hear Dan talking through the earpiece. And Will said, "Oh yeah, things are going great, and he's sitting on my lap right now." So that was the jumping off point for "Wish You Were Gay."

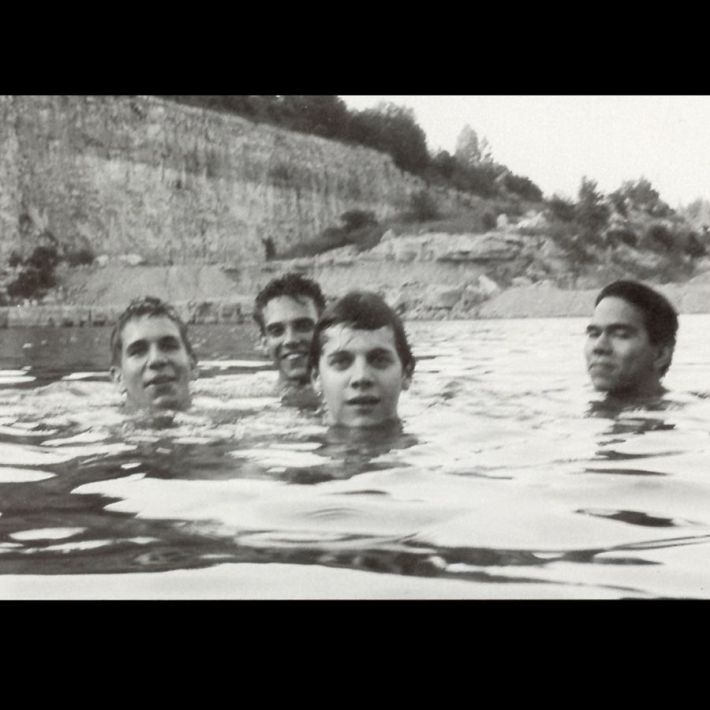

Shooting The Cover Photo For Slint's Spiderland (1991)

Were you taking a lot of photos at that time? Were you viewing yourself as a photographer? Or did you happen to be there with your friends?

OLDHAM: My dad was an avid amateur photographer, and we had a darkroom in the house. I seemed to be the one of my two brothers and myself who seemed to pick it up from him and become fascinated with it. And I loved spending time in the darkroom with him, and I loved taking pictures. And so from age 9, I think, to 18, my extracurricular activities were divided between kind of two main things. One of them was acting, and the other was just being involved as an observer-slash-photographer in the Louisville music scene. And I didn't play any music at all whatsoever until I was 18 or 19.

So I was just always around with a camera, and they just said, "Would you shoot..." Also, my dad took the photo from the first Slint record cover, and I'm in the picture there, behind the wheel of the car with a motorcycle helmet on. And they were just, you know, they were my best friends. Britt, Brian, Dave, and Todd were four of my very closest friends who I spent most of my social time with. And originally I had been invited to be in Slint because we were friends. They were like, "Would you want to be in a band?" And I was like, "Well, what does that mean?" They're like, "You can play some guitar or something." And they'd send me demos. I think at the time it was Britt, Ethan, and Pajo. Or maybe it was Britt and Brian and Ethan. And then after like six months, I'm just like, "I still don't know what to do." They're like, "OK, well, we've decided to ask either Dave or Brian to be in the band instead." I was like, "I think that's a good idea."

But yeah, we just spent a day, or maybe two days, going around places we knew in Louisville that were picturesque and taking pictures.

Was it your idea to have him get in the water?

OLDHAM: We wanted to go there cause it was easily one of the most beautiful places in our area, a place that we liked to go. And so we went there, and that water is just so beautiful and inviting. It's like, "Well, why would we be here and not get in the water?" And so we all got in the water. And the water there is like 20, 25 feet deep. So I'm treading water with my feet while holding the Pentax K1000 with my hands. So that's why it's slightly blurry also, because it was impossible to get perfect focus because everybody was in motion.

Trying not to drop your camera in the water too, I assume.

You mentioned acting was a main pursuit of yours when you were a teenager as well. Was that like stage acting at the time with you being in Kentucky, or were you traveling to Hollywood at all?

OLDHAM: I was definitely into movies from a very young age and into going to the theater at a very young age. And at the time we had inarguably one of the best local repertory theaters in the country at the Actors Theatre of Louisville. So I was going there, and my mind was being blown as a child. And so I started taking some acting classes and responded well to certain aspects of it and got deeper and deeper into that. And then I would audition for local TV stuff. And then the first film I was in was a movie called What Comes Around, which was directed by the country music great singer/guitar ripper Jerry Reed. It was the one movie that he tried to direct. It was a terrible movie, but I played a young Bo Hopkins. And it's interesting, that was my first time to Nashville as well, to make that movie. And another actor in it, Barry Corbin, who's friends with Ferg now, which is incredible.

And then I didn't have to go to Hollywood because at the time Actors Theatre, until very recently, had this decades-long running festival of new American plays sponsored by the healthcare giant Humana, in which playwrights would submit, or sometimes be commissioned, and get their first production of a play done in this festival that happened in early spring. And the world would come to Louisville to act in or write or see plays.

I remember I was in a play when I was 13 in 1983 called Food From Trash. And one of my co-actors in it was a guy named John Pielmeier who wrote a play called Agnes Of God, which was first produced here in Louisville as part of that but then was a movie with Jane Fonda and Meg Tilly maybe. I remember meeting — shortly after seeing Alien, my first R-rated movie — meeting Sigourney Weaver when I was 13 because she'd come to see the plays. Or watching actors like John Turturro, Holly Hunter, Delroy Lindo in plays, here again, all before I'm 15 years old.

There's a woman, I think her name is Barbara Shapiro, who's a big casting person, I think out of New York, who at the time was working for John Sayles. And they were trying to cast a regional actor to play a big part of this coal mining Union Wars movie that they were working on called Matewan. And so she said to John Sayles, "I saw this kid in this play in Kentucky, you might want to see him." And they sent me the script for that, and eventually I went up and auditioned for that and got that.

So I didn't go to LA until I was 19 and tried to get an agent, and got an agent, and pursued acting for a little while until I realized that it didn't have any of what I'd seen in the local music scene, for example, and the experiences of local bands with the national and international music scene. Or even the local theater scene. It was more cutthroat, more banal, far less interesting and less creator-motivated, it seemed like. I didn't know I wanted to make music, but I was just like, "Whoa, what the fuck am I gonna do with my life?" Like, I've literally been doing this since I was in knee pants, and now I see that it's something that is repulsive to me. And so I flailed for a couple of years. But I had already started writing songs, not knowing that it could be anything.

Starring In Kanye West's Alternate "Can't Tell Me Nothing" Video With Zach Galifianakis (2007)

OLDHAM: Galifianakis reached out a couple of times. He had this idea that in his standup routine, he would tell jokes, and I would come onstage with a guitar and sing the punchlines to the jokes. Which sounded fun, but he kept suggesting, like, "Can you be in LA on the 17th of February?"And I said, "No, I can't." But we had a communication going at that point.

And then at one point he said, "Well, listen, I'm from North Carolina. I have a farm. Please come visit me sometime if you ever feel like visiting. And there was a point where I was kind of at my wit's end, not having a very good time in life. I needed to get away from Louisville, and I was like, "What the fuck am I gonna do? I don't know what I'm gonna do." And I thought, "Oh, I'll call Zack Galifianakis and see if he happens to be at his farm, and I'll just see, you know? And maybe I can go visit him." So I called, and I was like, "Listen, I need to get away, I need a place to go. Are you there and could I come?" He said, "Yeah, come on."

And he gave me directions, and I drove across, whatever, eight hours. And got there, road weary, emotionally exhausted, and went and sat on the deck with him and his fiancee, who's his wife now. And he's like, "Oh, I forgot to tell you. We're also making a music video this weekend." And like literally — I think I got there, we're talking, maybe he gives me a beer. Within 20 or 30 minutes, the small skeleton crew arrives. They have a boombox, they put the song on, they bring cameras out. And that begins like 48 hours of nonstop video making. And so it just kind of — it literally, absolutely just happened.

So since you were feeling like you had lost your way or needed something to recharge you, did you find that to be a restorative experience?

OLDHAM: It was incredibly restorative. I mean, it was kind of a reminder. Like, when I first got into acting, I think there was an experience — I was 10 years old. I'd done some acting summer camps. I got into this acting program here. And there were a lot of kids who were juniors and seniors in high school, and I was 10 years old. And at one point early on they were like, "OK, we got a gig. We're supposed to do an improv show for kids on a Saturday morning. Are you ready? You wanna do it?" And I did this improv show with these older kids. And I was just like, "Oh this is absolutely what I want to do with the rest of my life." None of my acting experience after that was ever anything like that at all.

But it was like that, you know. I feel like I pulled some of that approach to creating into making music. It's just that it's about reacting to the situation and being present, being prepared, being present, being audience aware and and colleague aware. But it's rare — like I got to, to some extent with this Purple Bird record because I'm in a room with insane improvisers. But again, with Galifianakis that weekend, it was just like, "OK, for some reason, he's treating me like a peer, like an improvisational comedy peer to some extent." He's definitely the ringleader and the mastermind of this, but every step of the way, I'm ready to be there, and it's happening, and it's working.

And so in that way, it did really recharge me and make me feel like, "OK, I do have some skill sets. And maybe they're not always being applied, but they're present, and I just need to keep diligently trying to focus my music practice so it incorporates more and more of these." Basically things that adhere to the "yes, and" theory of improvisational comedy but plays by the rules of music at the same time.

The Purple Bird is out now via No Quarter.