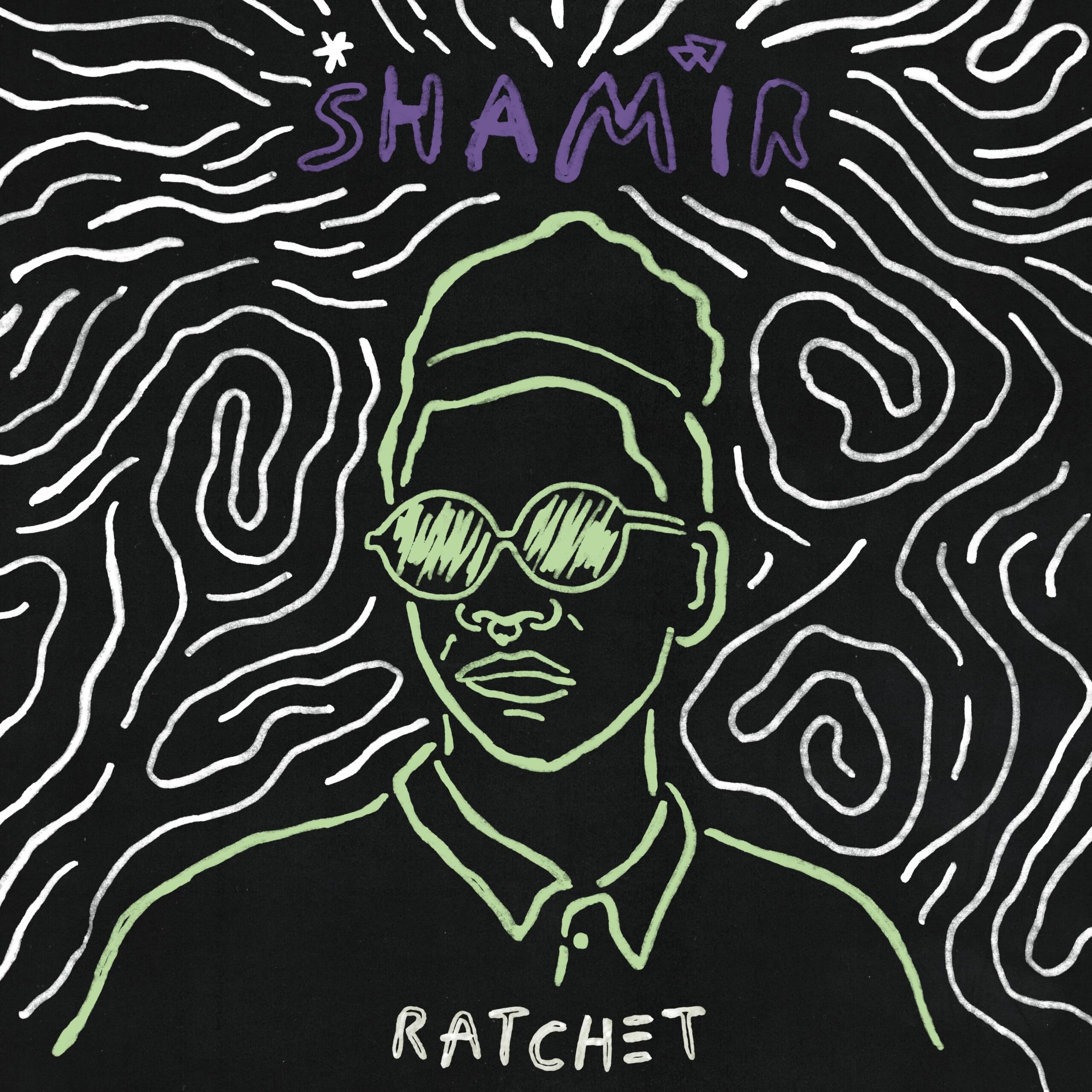

- XL

- 2015

It must have been strange to constantly hear yourself introducing yourself. "On The Regular," the breakout single from Shamir's debut album Ratchet — released 10 years ago today — opened with the 20-year-old Vegas countertenor rattling off a list of superlatives about himself over DFA cowbells and Lone-flavored chords, and it instantly bludgeoned the world over the head with the knowledge that this is the new thing you like! It's not a bad song by any means, but it's the kind of thing that can get out of control a little easily. You imagine Perfect Blue-style nightmares where the singer's own reduplicating face taunts him in the dead of night: "Hi hi, howdy howdy, hi hi!" If the ubiquitous Spotify ad wore on you, imagine how the person who soundtracked it must have felt, continuing to tell everyone day to day that this was "me on the regular" as if stuck in the disco version of Groundhog Day.

Small wonder he walked away from what looked like a serious pop career. "The wear of staying polished with how I'm presented and how my music was presented took a huge toll on me mentally," he said in the liner notes for his 2017 sophomore album Hope, self-released after giving up on a deal with the famous UK indie starmaker XL. His subsequent albums, leading up to this year's apparent swansong Ten, have mostly been painted in lo-fi bruise-wound guitar tones and released on indie labels like Father/Daughter.

He seems to know when he's said everything he needs to say. Who's to say another album on XL under the guiding hand of aberrant early-Pitchfork stylist-turned-Godmode boss/dance-pop kingmaker Nick Sylvester wouldn't have been the True Blue of its time? Yet it might've just as easily been the kind of watered-down disaster pop stars tend to whiff on for their sophomore effort, influenced by the samifying effect of the then-nascent streaming era.

Shamir decided to dodge the question entirely. Like Quentin Tarantino (and fellow mononymous sprite Lawrence, of the cult ‘80s pop project Felt), he's planning to end his career with 10 works. I've always suspected directors like the way their pop potboilers look in their filmographies next to their "serious" films, that Tarantino's pal Robert Rodriguez can smirk himself to sleep at night knowing that he gave the world Spy Kids and From Dusk Till Dawn. Likewise, I imagine Shamir can at least appreciate the way Ratchet stands like a glistening diamond amid the blistering shoegaze and post-grunge nastiness of his other albums, a hapax legomenon within his catalog that he has refused to allow to define him.

Over time, Ratchet has gained resonance from his decision to walk away. His affair with pop is more interesting for being unconsummated. Revisiting Ratchet long after the brief sliver of my junior year of college where it was the party album of choice both among my hipster friends and the queer cliques I tried vainly to get into, I expected to hear an ugly clash of wills — a young talent gamely going along with a cynical attempt to turn him into something he didn't want to be. What a surprise to hear such a sharp-edged little record, crackling with personality and brimming with twisty and intriguing little sonic details.

Sylvester pitched Shamir's music as like "R&B Yeezus," which seems inexplicable until you hear how Shamir floats on the heavy club scuffle of "Make A Scene." The music has less of a link to the watered-down post-Random Access Memories disco-pop on the charts at the time than rougher, queerer revivalists like Tiger & Woods, Horse Meat Disco, and Julio Bashmore. "On The Regular" got compared to Azealia Banks' "212" a lot, and it's an apt reference point, not just in its lopsided hip-house lope but in the way its fizzy synth chords and patina of vintage chintz had more to do with the music you were likely to hear on the runway than at the top of the charts.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

If Ratchet sounds like it was produced by a music critic, that's because it was. Shamir brought Sylvester with him from Godmode to XL, and you can hear shades of Chicago house and Latin freestyle and NYC mutant disco folded into this stuff, not least in the horn sections on several songs that hint at Arthur Russell's art-disco freakouts with Dinosaur L filtered through James Murphy's record collection. The bass is rubbery and cartoonish, not least on "Vegas," whose second half finds Sylvester tweaking the knobs for all they're worth.

Ratchet feels as much a statement of intent as a demo reel of the different modes the young singer can flit through, and he's not totally comfortable in all of them. "Call It Off" would be one of the album's best songs if Shamir didn't tiredly rattle off insta-dated internetspeak on the bridge's utterly unconvincing rap verse ("Never make a thot a wife/ No more basic ratchet guys"). The late-album power ballad "Darker" always struck me as an assignment Shamir couldn't quite handle, with his voice sticking out at strange angles. Even the showstopper "Youth" seems calculated to hit in an archdiva "Smalltown Boy"/"I Feel Love" kind of way, and though it's hard to reach those heights, it's the album's most pleasant surprise.

But one of the reasons Ratchet has aged nicely is that in retrospect, its almost aggressively introductory tone sets up a relationship with a pop star that turned out not to exist. If you like Ratchet and want more of the same, you have to meet him on his own terms on the later albums. They're so unlike this one that it feels vulgar to suggest Ratchet is "better" than them.

Ten years ago was a weird time. Pop was in the middle of a social-justice awakening and moral reckoning, but it handled it in painfully awkward ways, not least through a streak in the era's music criticism that posited the pop machine as a morally-sanctioned underdog. Guitars were out of fashion, resulting in great guitar bands like Tame Impala and Unknown Mortal Orchestra putting their pedals away and going disco. In that weird late-Obama lull following Peak Indie, people were seriously starting to wonder if rock was finally dead; I wonder if one of the reasons Shamir's turn to rock was so confusing to his audience was because a lot of his fans didn't want to hear rock at that time.

One way people processed this cultural shift was by playing up a supposed moral imperative to exalt queer artists, with the result being that artists like Shamir became fetishized for their identity despite talking about it very little in their music. Shamir talks about his queerness once on Ratchet, and it's on that same awkward rap verse from "Call It Off." "I think there has been so much trauma around me explicitly talking about my identity," Shamir told Stereogum a few years ago. "Because at the very beginning of my career, it was to the point of it feeling like it was exploited. Ratchet was not about my queerness at all. It was about growing up." Yes, and in more ways than he knew at the time.