"To be the man, you gotta beat the man, and...I’m the man." - The Nature Boy, Ric Flair

Statistically, there’s a good chance that you’re familiar with the classic rock canon, even if you don’t want to be. It’s blared at football games and dive bars. It soundtracks beer commercials and movies with motorcycles. It somehow screams out of your uncle’s acoustic guitar on Christmas Eve. Familiar are the lyrical tropes (plenty of sex, a lot of drugs, sex on drugs, and drugs compared to sex) and the talking points that defend them ("real music," "back when people played their instruments," etc.). And yet, in spite of this -- I hope I’m not alone here -- from ages 10 to 23, I was fooled. I regarded the denizens of the rock canon as musically infallible legends, who, barring their occasional missteps, knew something about music, something I couldn’t put into words. They were better than your average musician, much better than me at guitar, and had something to say, or something like that.

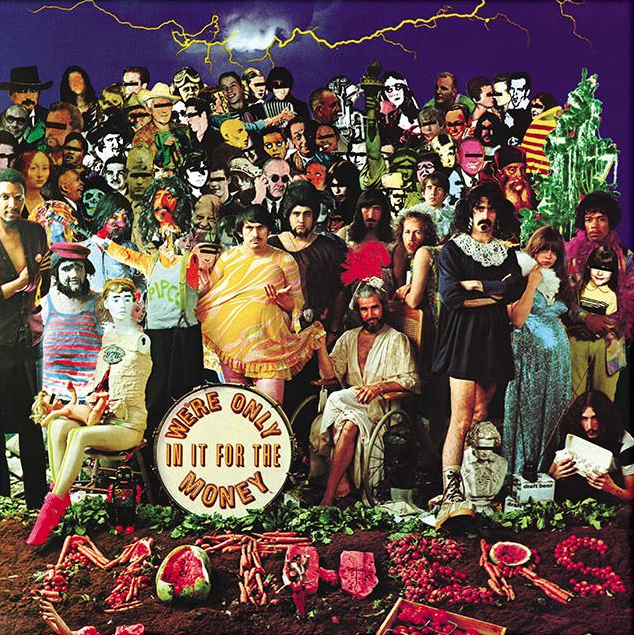

Thankfully, Frank Zappa unfooled me with his benchmark album We’re Only In It For The Money. Had it not been for Zappa’s fourth (and most obviously ironic) record, released 50 years ago this Sunday, I may have regarded groups like Ultimate Spinach, Vanilla Fudge, and the West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band as masters of their craft and not as the vapid pop groups of their time. There’s nothing wrong with that, either. If anything, it was on me to make that distinction in the first place. It’s even funnier that Zappa grouped the Beatles in with such artists, as evident by the album artwork. (I’d like to think it fooled some grandparents in its day, like your Nona buying you a Transmorphers DVD out of well-intentioned ignorance.) Nostalgia goggles don't work on the present.

Ever the contrarian, Zappa occupied a strange kind of space in popular music. For one, he fancied himself a composer, opting to work with orchestras in between excessive rehearsing, touring, and recording with the Mothers of Invention, his ever-evolving rock outfit that changed members like underwear. But that ever-evolving rock outfit was seen as an affront to the old guard of composers who saw him as a long-haired freak with vulgar material -- not a composer, by some definitions. As a Silent Generationer that lived into the 1990s, he saw the world of popular music switch directions countless times. There was no shortage of musical tropes for him to criticize.

Regarding the kind of criticism done for laughs, Zappa understood a core tenet of trashing any given genre of music: You don’t attack the music itself, you go for the jugular -- the subculture. The tangible stuff. Nobody wants to hear your critique of the I-IV-V progression or the standard pop song structure, but you can probably get a chuckle if you identify some lifestyle trends or holes in their ideology. We’re Only In It For The Money's second track, "Who Needs The Peace Corps?," establishes the tone of the next half-hour as a Zappa talkdown lists unofficial hippie commandments: “I will ask the Chamber of Commerce how to get to Haight Street,” “I will wander around barefoot,” “I will smoke an awful lot of dope,” etc. Of course you’ll do those things. You’re supposed to be a hippy, and that’s what hippies do.

For my money, "I will love the police as they kick the shit out of me" is the funniest singular Zappa lyric, beating out any masturbation or bestiality reference in his catalog. While primarily a dig at the youth, the lyric serves to remind you that he doesn't care for the Establishment, either. This agenda (or anti-agenda) is pushed further with "Mom & Dad," a song with the express purpose of calling out the idle parents of the Boomers, and is never without a counter; "Let's Make The Water Turn Black" narrates the adventures of two imbecilic friends Frank knew during childhood.

Even still, the verbal irony doesn’t hold a candle or stick of incense to the Big Picture irony that We’re Only In It For The Money is most easily enjoyed as exactly the sort of '60s rock record the Mothers are sending up. The colors are all there. Noisy passages, sing-song choruses, short skits, mono drums, airy acoustic segments, and mentions of San Francisco paint the album psychedelic, and Frank's laughing at you for enjoying it. In a Zappa-free vacuum, some segments would be called doo-wop or musique concrète, but synthesized together, We’re Only In It For The Money is a game-show wheel of generally bizarre shit, no matter what way you slice it.

Frank never cared for words much, anyway. "If I am going to HAVE to write some words, at least they'll be the truth, instead of some sentimental junk," he told Big Ten Magazine, in an article published two months after WOIIFTM came out. "But, the truth is really in the music. It's unfortunate that most of the American people need some kind of verbal content." The fact that it amounts to a psych-rock record is its greatest irony. If Frank Zappa made a record that was parodying your preferred genre of music, he would try to make it better than the source material while playing by (a few of) the source material’s rules, just so you can keep score.

It’s tempting to assign such unwavering naysayers with political centrism and the lot of do-nothing opinion-havers on the internet, and I don’t blame anyone that gets that vibe from WOIIFTM. The identified problems are the hippies and the Establishment; the Establishment kills (see "Concentration Moon"), while hippies are stupid and irritating (see "Flower Punk"). On the whole, it’s less of a coherent critique and more of a report on California in the late 1960s. When accepted as a document of the era, the insight of a man too young to be the Man, but old enough to try to beat him, takes on a new degree of importance, even on an LP with a song called "Hot Poop."

Additionally, answers shouldn’t be expected on a Frank Zappa record. This installment of songs, like pretty much every other one his albums, is a showcase of what one can accomplish within the confines of a medium. It doesn’t "transcend" psych-rock, but it does it differently (or sarcastically, at least). It captured the time period with a shit-eating grin. Five years later, the genre would be on its deathbed, and Zappa would still be cranking out albums that felt like they were mocking you for enjoying them.