Witch house was a joke -- literally. "2009 was the beginning of the 'witch house' style," Travis Egedy -- the Denver-based producer who makes distorted dance music as Pictureplane -- told Pitchfork at the end of that year. "Mark our words, 2010 will be straight up witchy." In the brief blurb, Egedy big-upped several artists in his creative circle as indicative of the witch house aesthetic, a sign at the time that this newly emerged subgenre of electronic music was actually a real thing; a year later, he was singing a different and decidedly un-occult tune. "It was never meant to be an actual genre," he claimed to The A.V. Club at the close of 2010. "It was a half-assed conceptual joke that really turned into something real."

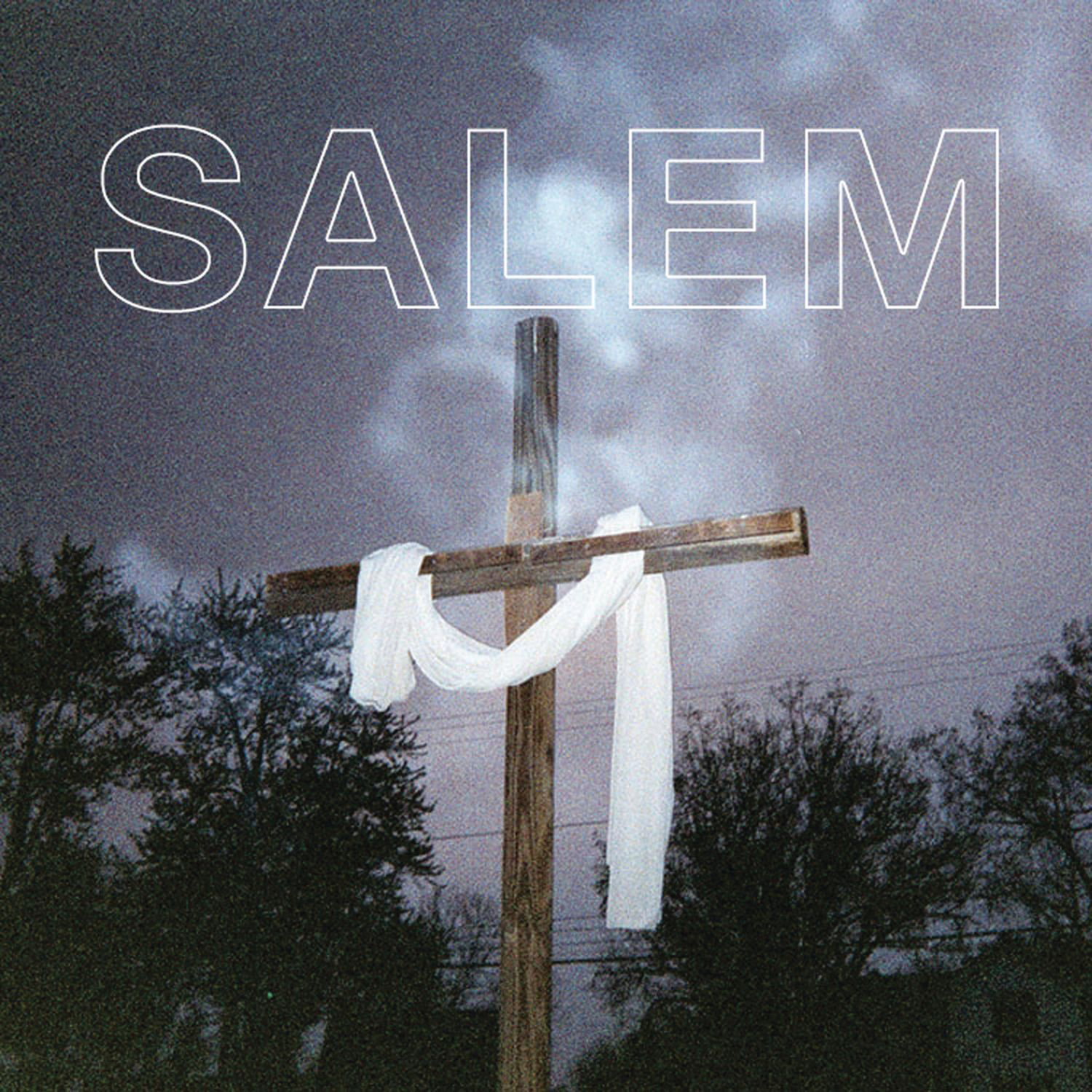

Indeed, similar to chillwave -- the sneakily influential subgenre of electronic pop that was coined by Carles of the defunct joking-not-joking Hipster Runoff blog and emerged concurrently to witch house's brief run -- witch house went from a goofy joke to a real-deal musical movement practically overnight. The existence of the subgenre was spectral in its brevity, lasting no more than 18 months before most of its practitioners disappeared off the map or moved onto different sounds and styles. The music itself was slight, with few actual lasting works of relevance beyond Midwestern trio Salem's 2010 debut LP King Night -- released 10 years ago today -- and the creation of Tri Angle, Robin Carolan's left-of-center electronic label that shuttered its doors earlier this year.

But beyond a few scattered points of legacy, the micro-phenomenon that was witch house is instructive in understanding how musical trends disseminated in the waning days of indie's music blog era. Witch house's aesthetic was established and strictly adhered to from its inception: slowed-down hip-hop rhythms that took direct inspiration from the syrupy sound of late Houston pioneer DJ Screw, glowy synths often ripped directly from trance music and rave culture, the occasional sound effect (i.e. the gunshots that punctuated NYC duo White Ring's 2010 single "IxC999"), vocals rendered unintelligible either by way of delivery or aural obfuscation.

There were a few indirect precedents for witch house's sound: the harshed-buzz gothic electro of Crystal Castles, the hauntological techno released by labels like Sandwell District and Modern Love (especially the latter imprint's founding act Demdike Stare), and the ever-present influence of UK decayed-rave maestro Burial. But Salem's influence loomed larger on witch house's pale shadow than any other artist. Arguably, witch house itself wouldn't have existed at all without them; despite Egedy's initial coinage of the phrase, few (if any) acts that deigned to adopt the genre tag made records that reflected his punk-ish rave music, instead attempting their own alchemic concoction from Salem's aural recipe.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=Ej7s8Bnq5_o

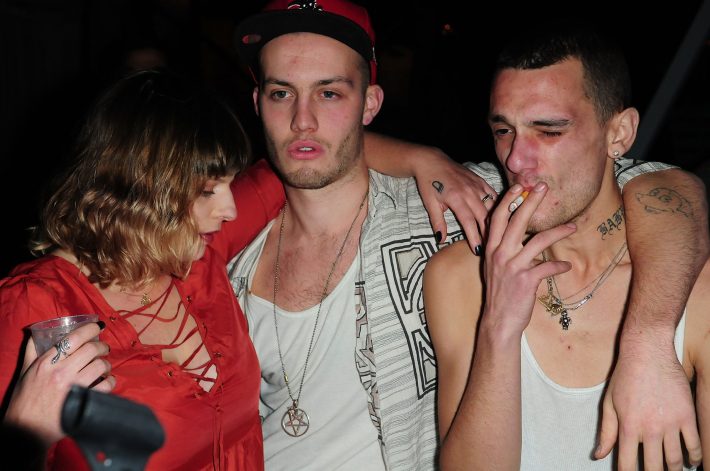

Band members Jack Donoghue, Heather Marlatt, and John Holland began attracting underground attention through early EPs released on the typically indie-pop-focused Acéphale imprint, as 2008's Yes I Smoke Crack and Water from the following year established the sound that the trio would crystallize on King Night. A fascinating and often beautiful amalgam of synth-pop, trance, and hip-hop motifs, the actual music on King Night was largely overshadowed by the controversy they often attracted. There were the terrible live performances, the botched New York Times interviews, and above all else the stench of cultural appropriation that arose from three white artists jacking the aural traditions of hip-hop and, at times, pitching their own voices to a low register.

A few factors (hip-hop and R&B becoming the dominant popular musical genres in the US, an increase in the diversity of music writers in the mid-2010s following decades of the form having been dominated by white men) contributed to the topic of cultural appropriation overshadowing the last decade of pop-cultural analysis. But Salem were arguably the first white act in the 2010s to kick off discussion of the ever-relevant issue, and that's where the trio's legacy begins and ends. "Never think of this band again," Christopher Weingarten implored in a Village Voice blog post naming King Night's "Trapdoor" one of the worst songs of 2010. "I assume [it] won't be the hardest thing come 2011." Indeed, after an EP the following year -- I'm Still In The Night, which featured a straightforward (for them, anyway) cover of Alice Deejay's "Better Off Alone" -- Salem more or less disappeared for the rest of the decade.

There were a few scattered remixes for the Cult and German photographer Wolfgang Tillmans, and Donoghue nabbed a production credit on "Black Skinhead," a single from Kanye West's abrasive 2013 LP Yeezus -- but otherwise the band remained an inactive concern until re-emerging at the top of this May with a new mix, STAY DOWN, for internet radio station NTS Radio, and releasing a Drain Gang-esque new single “Starfall" complete with footage of the band’s members engaging in some Twister-style storm-chasing.

King Night also marked the end of witch house as an existent genre that artists contributed to. The album's release had the inverse effect of the oft-cited legend surrounding the Velvet Underground's first album, as the overall proliferation of off-brand attempts to bottle their magic flatlined almost immediately. The evidence for this is largely anecdotal: During the genre's lifespan, I ran Pitchfork's Tracks section, which in its earliest inception served to cherry-pick up-and-coming artists that were highlighted on other music blogs, along with the occasional user submission that passed muster. Pre-King Night, my inbox was flooded with upstart bedroom-production hopefuls barely masking their mimicry, with unpronounceable, Wingdings-esque band names or overly on-the-nose monikers like Mater Suspiria Vision.

But in the months that followed the album's release, the frequency of similar-sounding submissions became slower than a witch house producer's BPM of choice; by the middle of 2011, bedroom producers had moved on to attempting replications of James Blake's dubstep-infused singer-songwriter pop, crystallized on his self-titled debut released at the top of that year. And even though some of witch house's more notable practitioners kept at it regardless (White Ring remained an active concern with a few different lineups, and their founding vocalist Kendra Malia passed away last year), other entities involved in the genre's sole wave moved on quickly -- including Carolan's Tri Angle imprint, which featured witch house practitioners like oOoOO (pronounced "oh"), Holy Other, and Balam Acab on some of its earliest releases.

Prior to Tri Angle's inception, Carolan wrote for 20jazzfunkgreats, a music blog known for highlighting dark, challenging electronic music new and old. More so than their contemporaries, the site and its writers maintained a healthier curiosity beyond mere trend-chasing impulses. And that willingness to break beyond genre carried over to Tri Angle's curatorial approach, setting it apart from witch house-adjacent imprints of the era like Disaro and Pendu Sound and carrying it to greater success than its peers.

Besides releasing seminal albums from left-of-center artists like How To Dress Well, the Haxan Cloak, and Forest Swords, Tri Angle often flirted with mainstream pop right as mainstream pop's figureheads started looking towards indie culture. Artists on its roster collaborated with artists ranging from Kanye and A$AP Rocky to Björk and Khalid. At least one of their associated acts became out-and-out pop stars: UK pop duo AlunaGeorge, whose hit single "You Know You Like It" was the title track of their 2012 EP released by the label before moving onto major-label territory.

The fact that Tri Angle achieved a lasting longevity at all seems like a minor miracle when considering the ephemera of the internet culture in which it rose from, and its closing in April felt like the end of an era that had regardless long ceased to exist. Alongside chillwave, the micro-phenomenon of witch house as a logged-on DIY movement has since been unreplicated within indie culture, with much of the grassroots musical movements of the late 2010s taking place squarely in hip-hop's SoundCloud-situated axis. (The chill-adjacent vaporwave culture comes close, but still hasn't yet achieved the level of mass music press saturation that chillwave and witch house were awarded.)

That doesn't necessarily mean the sensation is impossible to replicate, however -- on the contrary, we're more situated for something similar to emerge than ever before. As I theorized last year, both chillwave and witch house emerged from the wake of young people recovering from what was then the biggest economic collapse of their collective lifetime. Structural and direct violence were more visible and normalized through the digital age, jobs were nowhere to be found, and many just-out-of-college post-adolescents found themselves at home with nothing to do, nowhere to go, and sparse wealth beyond what their own imaginations might conjure. Sound familiar? It's unlikely that whatever musical movement that emerges from the age of COVID-19 will even remotely resemble witch house's confines -- but the micro-movement's spirit just may well come to haunt us again.