Motown Records famously had a finishing school, run by Maxine Powell, where their artists were taught how to smile, how to dress, how to move both onstage and off, and generally how to conduct themselves like artists and entertainers. Sometimes I feel like jazz could use something similar. There are some folks who dress well and recognize that the audience can see them as well as hear them, but a lot of (mostly male) jazz musicians are seriously lacking in the style and visual presentation department. The photos in their albums all too often look like nobody told them it was Picture Day. (Note: the photo of the Black Art Jazz Collective above is an exception.)

This realization becomes even more stark when confronted with classic jazz photography from the 1950s and 1960s, as I was when a series of coffee-table books landed in my mailbox the other week. Each one is a collection of work by an individual photographer -- Francis Wolff, William Claxton, and Jean-Pierre Leloir -- and the images are just incredible.

Wolff was one of the co-owners of Blue Note Records, along with Alfred Lion, and he attended almost every recording session, snapping away between takes in stark black and white. Some of the more than 150 shots in his book, which include images of virtually every iconic Blue Note artist of the 1950s and 1960s (Wolff died in 1971), have been published before, but there are many others that will be new to you, as they were to me, and they’re all stunning.

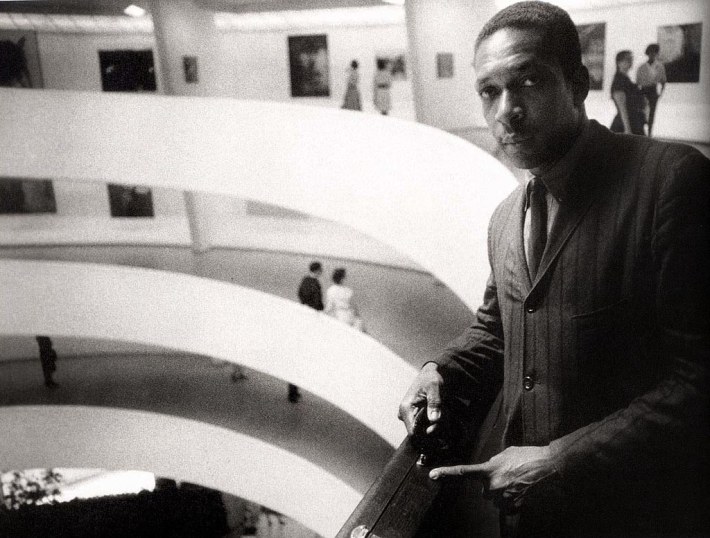

Claxton was also largely associated with a single label -- he was the art director for Pacific Jazz, the imprint that cemented the West Coast “cool” sound of the 1950s. Consequently, there are a lot of photos of trumpeter Chet Baker in his book. (He took Baker’s first professional photos.) But that wasn’t all he did. He shot for Life and Vogue, published more than a dozen books of his work during his lifetime, and won numerous awards. Claxton’s book includes shots of Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman, Art Blakey, Charles Mingus, Art Pepper, Lee Morgan, Thelonious Monk, Wes Montgomery, Sonny Rollins, and many others, including this fantastic photo of John Coltrane at New York’s Guggenheim Museum in 1960.

The third book might be the most revelatory of all. Jean-Pierre Leloir was a French photographer who shot for Jazz Hot magazine and other European publications, but what he preferred to do was capture musicians during their down time, so a lot of these shots were taken backstage, in airports, in dressing rooms, or while the players were enjoying themselves between shows. There’s a real intimacy to them; these are shots of musicians smiling, relaxing, and being humans rather than music legends. And they all look impossibly cool while doing it. These books should be passed around to young jazz musicians, in the hope that visual style will make a comeback.

I also read a really interesting book this month. Harald Kisiedu’s European Echoes: Jazz Experimentalism In Germany 1950-1975 is a concise but fascinating study of how avant-garde jazz blossomed in Germany, focused on four artists in particular: saxophonist Peter Brötzmann, trombonist Manfred Schoof, pianist Alexander von Schlippenbach, and East German saxophonist Ernst-Ludwig Perowsky, with whom I was not familiar. The book delves not only into the biographies of these artists and how they worked together and separately, but also provides broader political and cultural context and examines how German jazz sought specifically to acknowledge and engage with the music’s American, and specifically Black, roots. Some European improvisers of that era strove to separate themselves from jazz and the blues, and carve out a separate European space, but Brötzmann, in particular, has always made his ties to jazz history explicit. There’s a long quote from him toward the end of the book:

Even when I do my wildest shit and my so-called avant-garde nonsense, I want to show, especially the young folks, that it has a relation to the tradition and to the history. I mean, in Europe it’s quite easy to forget where the music comes from. It’s American music, and the sources and the roots are in the American entertainment industry, and that’s one of the points I wanted to make clear.

What’s cool about that quote is that it comes from an interview I did with Brötzmann in 2019, for Bandcamp. I had no idea I was going to turn up as a footnote in this book when it landed in my mailbox, but there I am in the Bibliography section. Even if I wasn’t mentioned in it, though, this would be an excellent and valuable book that counters some powerful myths about the supposedly vast gulf between American and European jazz.

Some New York jazz clubs have started offering streaming live performances. The Village Vanguard has featured Vijay Iyer with a new trio; saxophonist Joe Lovano, bassist Ben Street, and drummer Andrew Cyrille; and most recently pianist Eric Reed’s quartet with saxophonist Stacy Dillard, bassist Dezron Douglas, and drummer McClenty Hunter. Tickets are $10 for their shows, which are accessible through their website, and they’ve been excellent, shot with multiple cameras and great sound. Smalls also has musicians nearly every afternoon/evening now, playing from roughly 5 to 6:30 PM New York time on their site. The Blue Note and the Jazz Gallery are also offering live performances, chats with musicians, and other things. It doesn’t offer the same experience as being there in person, but the performers are clearly thrilled to be back playing for listeners, and that comes through in every note.

Finally, a great archival release from a while back has landed on streaming services. Alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley’s Swingin’ In Seattle: Live At The Penthouse collects radio broadcasts from 1966 and 1967, when Adderley’s band included his brother Nat on cornet, Joe Zawinul (who’d later play with Miles Davis on In A Silent Way, and form Weather Report with Wayne Shorter) on piano, Victor Gaskin on bass, and Roy McCurdy on drums. This is soulful groove jazz, but it’s also adventurous and the band is willing to stretch out quite a bit, without ever getting so abstract that the crowd can’t move to the beat. Here’s “74 Miles Away”:

And now, here are the best new jazz albums of the month!

Black Art Jazz Collective, Ascension (HighNote)

Saxophonist Wayne Escoffery, trumpeter Jeremy Pelt, and trombonist James Burton III formed the Black Art Jazz Collective in 2013, in order to stake their claim within a particular branch of the jazz tradition. Their music is high-level acoustic jazz, featuring intricate melodies and carefully balanced harmonies atop hard-swinging rhythms -- it’s a style exemplified by players like Woody Shaw, McCoy Tyner, Cedar Walton, Charles Tolliver, Joe Henderson, Jackie McLean, and others in the 1970s and early 1980s, when jazz was at a low ebb in terms of popularity. This is the third BAJC album, and it features an entirely new rhythm section: Victor Gould on piano, Rashaan Carter on bass, and Mark Whitfield Jr. on drums. “Twin Towers” was written by Jackie McLean as a tribute to Escoffery and Jimmy Greene, both of whom were in his band in the 1990s. He never recorded it, though, so Escoffery pulled it out of a drawer for this album. It starts with a beautiful intro from Gould, but the horns come in fast and furious, pushing through a spiraling, complicated melody, and the bass and drums drive hard as hell.

Stream “Twin Towers”:

Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers, Just Coolin’ (Blue Note)

This is a real discovery: an entire studio album by one of the greatest bands in jazz history, recorded but never released until now. The 1959 version of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers featured Lee Morgan on trumpet, Hank Mobley on tenor sax, Bobby Timmons on piano, and Jymie Merritt on drums. They recorded a double live album, At The Jazz Corner Of The World, at New York’s Birdland club in 1959, and soon afterward, Mobley left the group to join Miles Davis’s band; he was replaced by Wayne Shorter. Before that happened, though, they entered the studio and cut these six tracks, which Blue Note shelved because they thought the live material had more energy and punch. Three of the tracks from the live album are present here, including the opening “Hipsippy Blues.” The studio version isn’t so much softer as more sophisticated. Morgan and Mobley were a fantastic team, able to lock in perfectly and yield to each other smoothly when it was time for either man to take a solo. Behind them, Blakey’s beat is powerful, but not as apocalyptic as it could be; he’s giving them room to roam, and they make the most of the opportunity.

Stream “Hipsippy Blues”:

Eddie Henderson, Shuffle And Deal (Smoke Sessions)

I love this record, but I can’t write about it because I wrote the liner notes. So I’ve asked Nate Patrin, fellow Stereogum contributor and author of Bring That Beat Back: How Sampling Built Hip-Hop, available now, to help out. Here’s Nate!

The Ferrari that trumpeter Eddie Henderson's sitting on for the cover of his new album Shuffle and Deal might be '70s vintage, as are his most famous and successful records. But the trumpeter best known for his fusiony, funky, disco-laced hits as a bandleader that decade -- and to hip-hop beatmakers long after that -- has spent his later career reaching a couple phases further back in time. His ’90s reemergence as a hard-bop preservationist carries through to his new one, with the personnel ranging from Nouveau Swing alto sax player Donald Harrison and secret weapon bassist Gerald Cannon to fellow ’70s ensemble-cast vets Kenny Barron (piano) and previous Headhunters bandmate Mike Clark (drums). The bluesy strut of the title cut is a highlight, sure-footed even as its improvisations take inspired hairpin turns; Henderson's emotionally resonant tone sounds weathered by experience while still feeling ageless. --Nate Patrin

Stream “Shuffle And Deal”:

Throttle Elevator Music, Emergency Exit (Wide Hive)

Throttle Elevator Music is a project led by producer and Wide Hive label owner Gregory Howe, along with fellow songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Matt Montgomery, but the real draw is saxophonist Kamasi Washington, who’s on all six of their albums, beginning with their self-titled 2012 debut. The music is a blend of jazz, punk, and dub, at times approach the fire and fury of Bad Brains if they’d invited Washington to replace vocalist H.R. This album contains alternate versions of tracks from previous releases, plus some never-before-heard tunes; “Art Of The Warrior” features both Washington and trumpeter Erik Jekabson soloing over fierce guitar riffs from Ross Howe and driving double drums.

Stream “Art Of The Warrior”:

Gerald Clayton, Happening: Live At The Village Vanguard (Blue Note)

After several albums for Motema, pianist Gerald Clayton has signed with Blue Note. His label debut is a live album featuring alto saxophonist Logan Richardson, tenor saxophonist Walter Smith III, bassist Joe Sanders, and drummer Marcus Gilmore. The music has a dignity and gravitas that seems almost imposed, like the weight of history within the building has pushed the musicians into a particular mold. They don’t want to let their forefathers down. It’s like they’ve never seen an old-school jazz legend cut up, tell jokes and grin in between tunes at a club. I know I have. Anyway, they’re all superb musicians, and the compositions are solid and well played. “Rejuvenation Agenda” starts with solo piano, but Sanders and Gilmore create a thumping groove like a giant digging itself out of the earth, and Richardson and Smith harmonize well. Still, you may find yourself wishing they’d lighten up a little.

Stream “Rejuvenation Agenda”:

Charles Tolliver, Connect (Gearbox)

Charles Tolliver is a legend not just for his fierce trumpet playing, but for his leadership. He started out in the 1960s, playing with Andrew Hill, Jackie McLean, and Max Roach, among others, but at the end of the decade he and pianist Stanley Cowell formed the Strata-East label to release their own music and that of other adventurous, forward-looking players; Strata-East’s catalog has been rightfully worshipped in progressive jazz circles ever since. This is his first album as a leader in over a decade, and it features some killer musicians, including alto saxophonist Jesse Davis, pianist Keith Brown, bassist Buster Williams, and drummer Lenny White. The opening “Blue Soul” lives up to its title, digging deep into the blues atop a driving rhythm that could just as easily have anchored a Motown track. Both he and Davis take taut, high-energy solos until smoke is coming from the speakers.

Stream “Blue Soul”:

Joshua Redman/Brad Mehldau/Christian McBride/Brian Blade, RoundAgain (Nonesuch)

In 1994, saxophonist Joshua Redman was riding a wave of press adulation, and his third album, MoodSwing, was regarded as his best work to date. It featured Brad Mehldau on piano, Christian McBride on bass, and Brian Blade on drums, all of whom were up-and-comers at the time. In the quarter century that’s followed, they’ve each put a major stamp on jazz as leaders and sidemen, and now they’ve reunited. In the interval, each man has only sharpened his command of his instrument and of the music, so where MoodSwing had some moments that felt like young men trying on hats and making faces in the mirror, this is assured, swinging music with no illusions about itself, or aspirations it can’t meet. “Right Back Round Again,” written by Redman (as on the previous album, all the music here is original) is a leaping, sprinting tune that allows the rhythm section room to dance as the saxophonist takes a murmuring but high-energy solo, with Mehldau matching his enthusiasm and creativity.

Stream “Right Back Round Again”:

Christian Sands, Be Water (Mack Avenue)

Pianist Christian Sands’ latest album was originally supposed to come out in May, but then jazz caught the ’rona and a bunch of records were delayed. Anyway, it’s out now and it’s really good. The core band features bassist Yasushi Nakamura and drummer Clarence Penn, with guests -- trumpeter Sean Jones, trombonist Steve Davis, saxophonist Marcus Strickland, and guitarist Marvin Sewell -- showing up here and there. This track, a version of Blind Faith’s “Can’t Find My Way Home” begins with almost detuned bass thumps, but when Sands strikes the keys, he’s playing in an almost New Orleans rock/R&B style, reminding me of Leon Russell and/or Dr. John. Nakamura’s solo is forceful, like he’s trying to yank his fingers loose of the strings, accompanied by subtle shaken percussion before the piano comes pumping back in. This is a heavy, committed performance from everyone involved, transforming this song into something transcendent.

Stream “Can’t Find My Way Home”:

Ana Ruiz, And The World Exploded Into Love (Independent/Self-Released)

I had never heard of Ana Ruiz until this month, but she’s been making free music -- not only free jazz, but all sorts of avant-garde and experimental work -- in Mexico City since the early ’70s. Her ensemble Atrás del Cosmos (Behind The Cosmos), with saxophonist Henry West and drummer Robert Mann, later adding bassist Claudio Enríquez, was one of the first free jazz groups in Mexico, if not the first, active from 1975 to 1983. Because of their name, people assumed they were some kind of hippie spiritual jazz act, but it was actually chosen because they lived ... behind the Cosmos movie theater. Only one cassette of their music exists, though there’s apparently a vast archive of unreleased rehearsal and concert recordings. Anyway, this is basically Ruiz’s debut album, at the age of 68, and it’s awesome. Her piano style is very free, but classically influenced and even romantic. The eight-minute “Crines” (“Manes”) reminds me of the work of Matthew Shipp, the way it rumbles through the keyboard’s low end, then shifts to a melancholy, almost haunted melody.

Stream “Crines”:

Renell Shaw, The Windrush Suite (Vortex Jazz Club)

Vortex is a London club that provides a space for jazz, noise, and all sorts of experimental music. Naturally, they’ve been hit hard by COVID-19, and some artists have donated recordings on Bandcamp, the proceeds from which are going to keep the club’s rent paid until they can reopen. The Windrush Suite is a full studio album assembled by multi-instrumentalist and producer Renell Shaw, joined by Taurean Antoine-Chagar on saxophones, Orphy Robinson on vibes and marimba, Ayanna Witter-Johnson on cello, Samson Jatto on drums, and vocalists Delycia Belgrave and Nandi. The title refers to the “Windrush generation,” West Indian immigrants who began coming to England in the late 1940s following the establishment of the British Nationality Act Of 1948. In 2017-18, many immigrants who arrived before 1973 were threatened with deportation if they could not prove their right to remain in the UK. Anyway, the music is a swirling suite full of heartfelt, virtuoso instrumental performances, politically biting lyrics (and evocative recordings of immigrants telling their stories), and hard-driving beats. And the money goes to a good cause, even if you’ll never get to London to visit the club.

Stream “Bacchanal”:

Jorma Tapio & Kaski, Aliseen (577 Records)

I got to see legendary Finnish saxophonist Jorma Tapio perform in a tiny café in Helsinki a couple of years ago. That night, I bought the self-titled debut CD by his trio Kaski. Their work combines spiritual free jazz of the John Coltrane/Albert Ayler/Pharoah Sanders school with Finnish musical traditions, and is deeply rooted in the rural life of that country. The word “kaski” describes a way of burning a forest to make the ground fertile again, and the album title, Aliseen, is the Finnish word for a shaman’s trip to the underworld. The opening track, “Reppurin Laulu,” translates to “backpack song,” thus implying that the entire album is a journey, and it sounds that way. The hand percussion and throbbing bass give it an indigenous Arctic Circle feel, and Tapio’s keening alto saxophone sounds like it’s coming from the depths of a forest.

Stream “Reppurin Laulu”:

David Torn/Tim Berne/Ches Smith, Sun Of Goldfinger (Congratulations To You) (Screwgun)

In December 2010, saxophonist Tim Berne, guitarist David Torn, and drummer Ches Smith played a gig together in Brooklyn. Berne and Torn had been working together for years; Smith was the new guy, and would quickly find himself drawn into the saxophonist’s pool of collaborators. In 2019, this trio recorded a studio album, Sun Of Goldfinger, for ECM. This disc, on Berne’s own Screwgun label, features almost 45 minutes of music from that very first Brooklyn performance, and another track from a later show in London. The opening piece, “Bat Tears,” sets the tone for what this group’s sound would be -- lots of electronic warping of the instruments, and spacious, amorphous soundscaping. Torn’s guitar always sounds like an interstellar storm, here more than ever, and Berne’s playing on both alto and baritone is ferocious, with Smith rattling the drums out of their housings.

Stream “Bat Tears”:

The Great Harry Hillman, Live At Donau115 (Independent/Self-Released)

The Great Harry Hillman (he was a runner and hurdler who won three gold medals at the 1904 Olympic Games) are a Swiss quartet whose music is a combination of jazz and moody post-rock. This live album is composed of entirely new music which displays the same inner calm and experimental spirit as their three studio albums. “Cruise Tom Cruise” is built on a bluesy melody played by guitarist David Koch in a biting, Bill Frisell-ish manner, as bassist Samuel Huwyler and drummer Dominik Mahnig tick and boom their way along behind him. Bass clarinet player Nils Fischer isn’t so much playing notes as making various squeaking and hissing noises, like someone let an animal into the room and it’s a little frightened by what’s going on. Gradually, the energy builds, and Fischer gets a little closer to taking a co-lead role with Koch, but always seems somewhat tentative. Also, there’s no applause between pieces, making this album seem like a recording of a quarantine live stream.

Stream “Cruise Tom Cruise”:

Brian Krock, Viscera (Independent/Self-Released)

Alto saxophone and clarinet player Brian Krock leads a large band, Big Heart Machine, as well as a quartet, Liddle. Viscera features five new pieces written just before Liddle launched a three-week tour in support of its self-titled 2019 debut; it also includes re-recordings of two tracks from the earlier album, “Saturnine” and Anthony Braxton’s “Composition No. 23B,” likely one of his most well-known pieces. This album was recorded live at Firehouse 12 in Connecticut, but there’s no applause on the album and the sound is pristine, so I emailed him to ask what the story was. He told me, “I made the choice to leave out the audience’s applause and to take advantage of the great recording equipment they have at Firehouse 12 and mix the album more like a studio album. I had originally intended to take the band into the studio, but after playing 16 shows over the course of 3 weeks, I thought the energy of the live sets was probably better than what we could accomplish in the studio. Luckily, Firehouse 12 was our last tour stop.” “Nurturing A Vulture (In My Body)” is one of the new tunes, and behind that fantastically evocative/creepy title is a dark, brooding piece of music. Guitarist Olli Hirvonen, bassist Marty Kenney, and drummer Steven Crammer set up a kind of Americana-ish post-rock rhythm, over which Krock heads into an almost out-of-body zone where his clarinet lines squeal and squawk, tones getting longer and longer until they disintegrate into free jazz cries as the drums clatter and tumble.

Stream “Nurturing A Vulture (In My Body)”: