May 13, 1989

- STAYED AT #1:1 Week

In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

Sometimes, the pop charts go through periods of deep, stultifying stasis, just waiting for something new to come along and kick some dust up. That, I would argue, is what was happening in 1986, before Bon Jovi came blasting through with "You Give Love A Bad Name." That year, most of the dominant pop hits were overblown treacle. This was an era of gloopy balladry and self-satisfied smarm, of Starship and Mr. Mister and Steve Winwood. Then Bon Jovi showed up. Their monster hit Slippery When Wet blew the doors open for glam metal and for a particular kind of rowdy energy that simply hadn't had a real shot to conquer the Hot 100 before. After Bon Jovi, Whitesnake and Guns N' Roses and Def Leppard and Poison all had their own #1 hits, and a new era began. That breakthrough, combined with the similarly game-changing success of Janet Jackson's Control, signaled that a whole new generation was about to start deciding the fate of the Hot 100.

Other times, though, pop music moves fast. Sometimes, we get these brief and glorious flurries of action and activity, where ideas that have spent years building under the surface suddenly break through and take over. Maybe a few established stars switch their styles up and find new life. Maybe a new star arrives. Maybe a few one-hit wonders channel fresh sounds into mass entertainment and then disappear, their jobs done. Those moments of pop inspiration, where the charts suddenly seem fully energized, happen for all sorts of different reasons. You can't forecast them, and you don't know when they're going to arrive. But when those moments happen, they're beautiful.

One of those beautiful moments came along in the first half of 1989. New and different sounds -- new jack swing, house, rap -- started making serious inroads into pop consciousness. There are some deeply wack chart-toppers in that era, but there are plenty of great songs, too. Many of those great songs spoke of changing times. Bobby Brown and Paula Abdul and Roxette and Fine Young Cannibals and a reenergized Madonna all made #1 hits with songs that felt fresh and new and exciting.

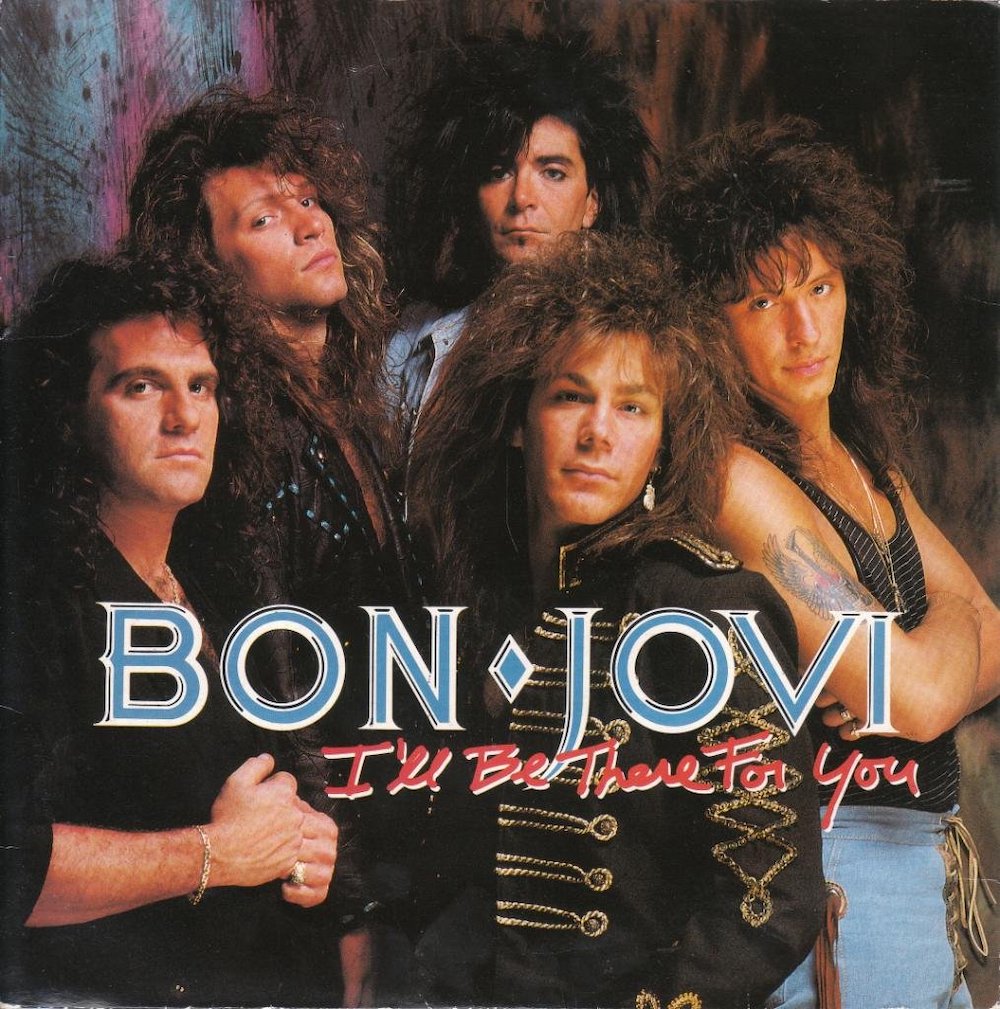

In that context, less than three years after their big breakthrough, Bon Jovi sounded tired. The band was still hugely popular, and they were still cranking out hits more reliably than their poodle-haired peers, but they weren't surfing on the zeitgeist anymore. "I'll Be There For You," Bon Jovi's fourth and final #1 hit, is a perfectly satisfying arena-rock jam, a song that can still incite mass singalongs. But in the context of its moment, there was nothing exciting about the song. Sometimes, that's just how it goes.

You can't blame Bon Jovi for putting out a song like "I'll Be There For You" when they did. Bon Jovi had just made a world-crushing breakthrough with Slippery When Wet, and when they followed that album up with 1988's New Jersey, they did everything they could to re-bottle that lightning. They recorded at the same studio, with the same producer and the same mixer, and they wrote a lot of their songs with the same co-writer who'd helped them come up with two #1 hits. The sound that they'd helped usher into pop dominance was still cresting. The week that "I'll Be There For You" topped the Hot 100, there was a whole lot more hard rock in the top 40: Guns N' Roses, Living Colour, Lita Ford and Ozzy Osbourne, Winger, Def Leppard, arguably 38 Special. Bon Jovi's timing was still on point.

A few months before that week, Bon Jovi had reached #1 with the extremely glam "Bad Medicine," the first single from New Jersey. After that hit, the band's follow-up single was the charged-up love song "Born To Be My Baby." Co-writer Desmond Child, the pop mastermind who'd helped turn Bon Jovi into a pop-chart force, envisioned "Born To Be My Baby" as a relatively stripped-down folk-rock experiment, and the band toyed with the idea of releasing it as an acoustic song. But producer Bruce Fairbairn convinced them to record it as a big, clean rocker, and that's what they did. "Born To Be My Baby" peaked at #3. For apex-era Bon Jovi, this was a relative disappointment. In Fred Bronson's Billboard Book Of No. 1 Hits, Child says, "Boy, [that] should have been #1." (It's a 5.)

Maybe "Born To Be My Baby" should've been a power ballad. Maybe that's the reason that Bon Jovi followed that single up with an actual power ballad. "I'll Be There For You" shows up late in the New Jersey tracklist, and it works as a kind of respite. New Jersey is rough going -- an overlong obligatory blockbuster sequel without the same energy and hunger as the original. It has hits -- a lot of hits, it would turn out -- but it also has pretensions at blues-rock classicism that don't work for a band as ecstatically plastic as Bon Jovi. The album also has a generally appalling lack of restraint. Apparently, Bon Jovi sincerely believed that people were genuinely hungering for multiple six-minute Bon Jovi songs. On the album, "I'll Be There For You" is a victim of that bloat, too. The LP version runs a ridiculous 5:41; the radio version, with a minute chopped off, is still too long. But even at that excessive length, "I'll Be There For You" lands.

There's some pretension in "I'll Be There For You"; I'd love to know whose idea it was to start the song with a sitar intro. But I like that sitar intro. I like the whole expansive vastness of the song -- the rising drone on the intro, the whispery opening line, the way it builds to massed heartbroken shouting. "I'll Be There For You" isn't as clean and sharp as Bon Jovi's best songs, but it still has a chorus that lands like a grand piano falling off a sixth-floor roof. As a band, Bon Jovi's single greatest strength is the power to trigger arena-wide communal yelling. From that perspective, "I'll Be There For You" is a roaring success. It's over-the-top even before the key change comes screaming in at the end.

When you start to think about the lyrics, though, things get dicier. As a piece of writing, "I'll Be There For You" is about as dumb as dumb gets. Jon Bon Jovi plays a guy begging for a lover to come back, and he opens things up nicely by quietly moaning that "I guess this time you're really leaving." But then, as he pleads, he gets more and more flowery with the verbiage, and he should not do that. The first verse, for instance, has a whole riff about tears becoming bodies of water: "You say you've cried a thousand rivers/ And now you're swimmin' for the shore/ You left me drownin' in my tears/ And you won't save me anymore." So both of them are changing their local topography by crying? That's too much crying. Later on, Jon starts talking about assuming fluid form himself: "I'll be the water when you get thirsty, baby/ When you get drunk, I'll be the wine." Hydro-Man Christ over here.

The song works pretty nicely, though, when you imagine it as just a dumb guy's lament. (Dumb guys have big feelings, too. I should know.) At the emotional climax, Jon howls out, "I didn't mean to miss your birthday, baby/ I wish I'd seen you blow those candles out." So maybe this is a musician on the road talking about everything he's missed back home; Bon Jovi love the road songs. But maybe it's just a guy trying out how halfassed take on poetic language to apologize for a very typical dumb-guy bungle. I like where Bon Jovi wails that "words can't say what love can do." That point is pretty debatable, but he's at least right that these words can't say what love can do.

"I'll Be There For You" happens to be Bon Jovi's only #1 hit that Desmond Child didn't co-write, which makes me wonder how often he served as editor for the fancier lyrical flights of co-writers Jon Bon Jovi and Richie Sambora. But "I'll Be There For You" does give Jon a chance to do some of his most effective vocal work. Jon Bon Jovi is a famously limited singer, but he puts a whole lot of force and emotion into everything. The chorus of "I'll Be There For You" is mostly half-drunk shouting, but if you're trying to get a whole arena to sing along, then half-drunk shouting is a good means to that end. Even the falsetto screech after the birthday-candles line, while not technically good singing, helps convey the message that this is a desperate guy and that he really wants you back.

For the "I'll Be There For You" video, Bon Jovi pulled out all their usual tricks. They were on tour at the time, so they just got regular director Wayne Isham, the hair-metal Hype Williams, to shoot them at Wembley Arena in London -- lip-syncing in an empty room and then sweatily belting stuff out in front of an adoring crowd. Richie Sambora wears a cowboy hat for the entire thing; a New Jersey guy should not be able to pull that off, but he makes it work. The big-crowd setting changes the meaning of the song a bit. In video form, "I'll Be There For You" becomes a song where Bon Jovi pledge fealty to their fans. Bon Jovi love talking about their fans, to the point of tedium. The video makes that mutual love a little more tangible.

The fans were there for Bon Jovi, too. After "I'll Be There For You," New Jersey yielded two more big singles. This gave the album a grand total of five top-10 hits -- the most of any hard rock album in history. The band followed "I'll Be There For You" with the overblown, ridiculous "Lay Your Hands On Me," which peaked at #7. (It's a 5.) After that, Bon Jovi made it to #9 with the tenderly horny "Living In Sin." (That one is a 6.) New Jersey didn't have anywhere near the impact of Slippery When Wet, but credit where it's due. That follow-up album had legs.

Bon Jovi spent a full year and a half on the road behind New Jersey. They went all over the world -- even making it to Moscow, where they headlined the Moscow Music Peace Festival over a bunch of other glam-metal bands. All the other bands got pissed off because Bon Jovi played last and had more pyro, even though the Soviet crowd was totally unfamiliar with them. (By some accounts, most of the crowd was there for Ozzy Osbourne, since Black Sabbath bootleg tapes had been hot commodities on the Soviet black market. I love that.) By the time all that touring was done, Bon Jovi were exhausted, and they were on the verge of breaking up. When they got back home, the members of the band didn't talk to each other for months.

They didn't break up, of course. Bon Jovi weathered the grunge-era storm, shed their big-hair trappings, and became a venerated staple on the arena rock circuit. "I'll Be There For You" was Bon Jovi's last #1 hit, but I'm not going to get into the last 32 years of band history here. We'll have another chance to talk about that. Bon Jovi won't appear in this column again, but Jon Bon Jovi will be in here as a solo artist.

GRADE: 6/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's the scene in the 2005 film A Lot Like Love where Ashton Kutcher sings a not-great version of "I'll Be There For You" to Amanda Peet: