Vivek Maddala is an Emmy-winning composer and a regular participant in The Number Ones Comment Section. After reading his takes on the music theory behind several historic hits, we invited him to turn his focus on more current singles. Welcome to our new column In Theory.

"Solar Power," the title track and lead single off of Lorde's forthcoming album, is a breezy, cheerful kind of summer anthem -- and a rather modest one. The song feels understated due to its dry production style, but more importantly, because of its simple and direct compositional architecture.

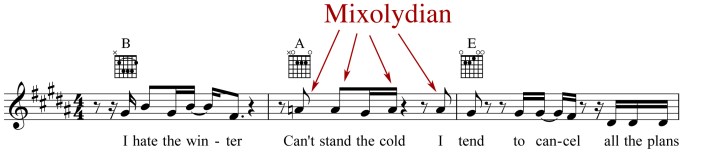

If you’ve heard some of Lorde's previous singles -- "Royals" and "Green Light" in particular -- you may recognize that the I-♭VII-IV chord progression and the accompanying Mixolydian mode feature prominently in both songs. So maybe it shouldn't come as a surprise that Lorde and co-writer/producer Jack Antonoff chose the same chord and modal structure to carry "Solar Power." Let's take a look at the song's underlying musical design and explore why it works the way it does.

First Principles

If you're unfamiliar with musical building blocks, let’s define some terms. In Western tonal music, there are 12 chromatic pitches that we denote using letters A through G, along with sharps (#) and flats (♭):A, A#/B♭, B, C, C#/D♭, D, D#/E♭, E, F, F#/G♭, G, G#/A♭. The distance between any two pitches is called an "interval" and you can combine intervals to create chords. We call the intervallic distance between adjacent pitches "semitones" (or "half steps") and two semitones make a "whole tone" (two half steps make a "whole step"). The standard major scale contains 7 pitches (separated by combinations of semi- and whole tones) to which we ascribe Roman numerals as follows: I, ii, iii, IV, V, vi, viio.

We use upper case Roman numerals to indicate that the chord built on that scale degree has a "major" quality, while lower case Roman numerals indicate the chord built on that scale degree has a "minor" quality. (You'll notice that the seventh degree is written in lower case, but it also has a small superscript circle -- meaning it's not exactly a minor chord, per se, but a diminished one. Diminished chords are lovely, valuable devices, but not relevant to Lorde's "Solar Power" -- so we'll save that for another time.) When composers construct tunes using only the 7 pitches comprising the scale, we call this a "diatonic" melody. If they introduce pitches outside of the 7 notes, we call it "chromatic" (or non-diatonic).

Each of the chords built on a scale degree brings with it a particular kind of emotional energy in relation to the other chords surrounding it. For example, the I chord (also known as the "tonic") feels completely stable and comfortable because we’re essentially "home." Everything is based around the I chord. In contrast, the ii chord and the IV chord both feel somewhat unstable relative to the tonic.There's something not quite resolved about them, and when we hear them relative to the tonic, a subconscious part of us wants them to move "home" to the I chord. The V chord is even more volatile relative to the tonic, and it feels as though a strong gravitational force is pulling us back to the I chord for resolution. Continuing in this fashion, each scale degree plays a particular kind of role, much like characters in a story. We're all familiar with narrative character types -- the protagonist, the antagonist, the love interest, the confidant, deuteragonists, tertiary characters, the foil, etc., and the ways in which they each have multiple functions in a story. Chords are like characters insofar as they serve one or more roles, relative to each other.

It's All Relative

Much like how scientists use the periodic table to organize elements, musicians organize the 12 chromatic pitches using the Circle of Fifths. Each key center is positioned in between the two other key centers with which they have the most in common. If we're looking at the key of C, for example, we can see that it has a lot in common with F, the difference being one flat (♭), and with G, the difference being one sharp (#). Furthermore, the key of C has very little in common with G♭/F#, as they’re farthest apart in the circle.

It's called the Circle of Fifths because as you travel clockwise from any key center, the next key is a "perfect fifth" interval up: The G Major chord is the V relative to C; the D Major chord is the V relative to G; etc. (As you travel counterclockwise, you'll see that each step takes you down a "perfect fourth": F is the IV relative to C; Bb is the IV relative to F; etc.)

What is the I-bVII-IV chord progression?

Lorde's "Solar Power" is ostensibly in the key of B, which contains the following notes: B, C#, D#, E, F#, G#, and A#. If we assign Roman numeral scale degrees, we can see that B is I (the tonic), C# is ii, D# is iii, etc. "Solar Power" contains only three chords: B, A, and E. If “home” is the B chord, and the IV chord is E, then what do we make of the A chord? It doesn’t fit in the key of B, does it?This is the "flat seven" chord—♭VII -- meaning they've flattened the seventh degree from A# to A. If each chord plays a certain role (or set of roles) in the song’s musical narrative, what role does the ♭VII chord play? This is a pretty juicy question that has been a subject of research and debate among composers and musicologists for centuries.

There's a classic musical progression known as the "plagal cadence." It's a way to resolve a musical phrase by going from the IV chord to the I chord. Sometimes this is called the "Amen cadence" because of its frequent setting to the text "Amen" in church hymns. A great example is the closing line in the refrain of the Beatles' "Yesterday," which resolves with a plagal cadence from B♭ to F. It's a kind of soft resolution that feels comforting, but not as definitive as the more common V-I resolution. Notably, Nicole Biamonte of McGill University has described I-♭VII-IV as a "double plagal progression" because the ♭VII is the IV relative to the IV chord. In other words, we can think of I-♭VII-IV as cascading plagal cadences, which is why the soft but not-so-absolute cyclical resolution that Lorde repeatedly uses in "Solar Power" conveys a sense of gentle buoyancy.

Let's pause the I-♭VII-IV discussion for a moment to examine a similar structure: the ii-V-I chord progression, which is a staple in Western harmony, and in jazz in particular. Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn's "Satin Doll" is a classic example. In this progression, the ii chord can feel a bit dark or brooding, but moving to the V chord injects a sense of optimism. Remember that the V chord is quite unstable and yearns to resolve to the I -- so when that chord arrives, it conveys a conclusive resolution. In the key of A, the ii-V-I turnaround would be Bmin-E-A. (We could substitute a B7 chord for the Bmin, and it pretty much functions the same way.) You'll notice that this represents adjacent stops on the Circle of Fifths, traveling counterclockwise from B. The satisfying, resolved feeling intrinsic to this ii-V-I progression is why it's so frequently used.

I believe the I-♭VII-IV progression has a similar characteristic, and by examining the Circle of Fifths relationships, we can see why: It's essentially the inverse of the ii-V-I progression; it uses the same chords, but travels in the opposite direction. However, unlike ii-V-I, which feels totally resolved, the I-♭VII-IV completes its cycle in a less-stable manner. It retains the comforting optimism of ii-V-I, but it still desires movement because it's not yet home. Lorde's use of the I-♭VII-IV progression in "Solar Power" invokes a feeling of constant motion, and its why she’s able to use it repeatedly without it becoming tiresome. If you imagine a Venn diagram, the chord progression exists at a rare intersection of "fulfilling" and "unsettled," injecting a sense of calm, while still inviting the listener to crave harmonic resolution.

It has always been my feeling that the I-♭VII-IV progression is so widely used in pop music for precisely these reasons.Guns N' Roses' "Sweet Child O’ Mine" and Lady Gaga's "Born This Way" are two (out of countless) examples of songs featuring it.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=1w7OgIMMRc4

https://youtube.com/watch?v=wV1FrqwZyKw

Modalality

The melody of "Solar Power" is purely diatonic and closely follows the outline of the I-♭VII-IV progression by employing Mixolydian mode. The standard major ("Ionian") scale contains the following degrees: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. Think: Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Ti. It's the most fundamental heptatonic (7-note) scale in Western music. The Mixolydian scale is identical, but with a "flat 7" (which cooperates nicely with the ♭VII chord) -- so we have 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, ♭7.Great examples of songs using Mixolydian mode include Miles Davis' "All Blues" and Madonna's "Express Yourself."

https://youtube.com/watch?v=-488UORrfJ0

https://youtube.com/watch?v=GsVcUzP_O_8

The mode was used quite a bit in Medieval Gregorian chants, and -- as its name implies -- traces its roots to ancient Greece. You can also find it in Carnatic music of South India, where it's known as Harikambhoji; and in Hindustani classic music it’s the Khamaj raga. A lot of iconic Afro-Cuban music uses Mixolydian mode, and its use is extremely popular in rock 'n' roll (the Kinks' "You Really Got Me," Boston's "More Than A Feeling," Bon Jovi’s "Bad Medicine," etc.). Famously, it is Mixolydian mode that gave the Beatles' "Norwegian Wood" its indelible charm.

Note that Lorde deploys the A natural note (♭7) only over the A (♭VII) chord, not over B or E. This is pretty "square" and an obvious use of Mixolydian mode, but it works nonetheless. ("Royals" uses Mixolydian mode much more powerfully and creatively by invoking a sense of portending opacity over the tonic (I) chord.)

Like in the verse, the pre-chorus uses the ♭7 in the melody only over the ♭VII chord.

In the chorus of "Solar Power" (assuming we can call the third section a chorus, the big coda notwithstanding), Lorde and Antonoff employ modal interchange by briefly implying Lydian mode. This is the one section of the song where the order of the chords breaks with the previously established pattern. Instead of I-♭VII-IV, we now have the (nearly identical) ♭VII-IV-I. Same pattern, just starting in a different place.

Lydian is a major mode similar to the standard major (Ionian) scale, but with a raised 4th degree. So it’s 1, 2, 3, #4, 5, 6, 7. Lecturing at Oxford University in 2016, film composer Thomas Newman memorably described the raised 4th as creating a sense of hopefulness and "rising." This description seems apt when you consider some well-known examples of Lydian mode: John Williams' "Flying" theme from E.T.; Leonard Bernstein's "Maria" from West Side Story; the octave-piano melodic hook in Tears For Fears' "Head Over Heels." In “Solar Power,” we hear a D# over the A Major chord, which is the song's brief foray into Lydian territory. This note (the #4) will inevitably happen when playing a diatonic B Mixolydian melody over an A Major chord (as the D# defines the “Major” quality in the B Major scale) -- so Lorde and Antonoff may not have planned out this modal jaunt. But nonetheless, the melody here performs its Lydian job by infusing a feeling of "rising" into what is, paradoxically, a descending melodic line.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=7AR6KQOiNHA

https://youtube.com/watch?v=CsHiG-43Fzg

Production

As with pretty much all pop music these days, some of the most compelling aspects of what we hear have more to do with presentation than substance. By substance, I mean composition (those things that can be copyrighted and that appear on the song's lead sheet). By presentation, I mean production -- i.e. performance, orchestration, sound design, recording and mixing techniques, etc. Nat King Cole's "Nature Boy," released in 1948, is exquisitely beautiful in no small measure due to Cole's breathtaking performance. But the song’s intrinsic writing is so undeniable that the tune cannot help but be a stunning piece of music no matter who performs it or how it is presented. In contrast, I think the elegant beauty of Lorde's music, like a lot of pop music these days, relies heavily on not just the writing but the entire package.

When Lorde released "Royals" in 2013, it was the song's arresting presentation that drew so much attention. The a cappella opening, supported only by a bare kick-and-snaps syncopated groove, awash in reverb, imparts a sense of emotional vagueness. Because the song starts with no chordal or harmonic reference, the melody is tonally ambiguous and the song implicitly asks listeners to project their own feelings into the void—almost as compensation for what it is not saying. The percussion groove sounds a little menacing, and we don’t hear the major (Mixolydian) quality of the melody until Lorde completes the last line of the verse. At that point, we’re already invested, and then she pulls a kind of harmonic bait-and-switch with a bright D-Major Mixolydian tune. The resulting experience is not confusing, but revelatory and delightful. Miles Davis' famed quip to Claude Debussy about the "space between the notes" being more important than the notes themselves may be the guiding religious principle for Lorde and Antonoff. And it serves them well.

"Solar Power" seems to attempt something like this, with an understated opening, but the result is less striking. Lorde sings her initial vocal in an alto range, quietly, and the treatment is extremely dry (no reverb or delay) with quite a bit of dynamic-range compression. This, coupled with the equally dry palm-muted acoustic guitar, creates a sense of immediacy -- like she and Antonoff are whispering in your ear. It's an attractive sound, but not until after two minutes into the song do we hear any significant contrast in the presentation. I understand the desire for a slow build, but unfortunately, the aforementioned recurring chordal and melodic lines aren’t compelling enough to sustain it. I suppose if the song’s lyrics were saying something insightful or incendiary -- or commenting on the human condition in some novel way -- then maybe that could support a slow musical build. (Claiming to be a prettier Jesus because "hey let's go to the beach" isn’t exactly profound -- but it is fun.) Lorde's stacked-octave vocal doubling is impeccable, and Matt Chamberlain's deep-pocket drumming (reminiscent of Gota Yashiki's Groove Activator) is so right. All the component parts are there, but in the aggregate, it's just... fine.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=I1r1lQwvnKk