It's happened before. In 1979, 11 people died while trying to rush the door to see the Who inCincinnati. In 1991, a crowd crush outside a Puff Daddy-promoted celebrity basketball game at New York's City College killed nine people. In 2000, nine people died at Denmark's Roskilde Festival while Pearl Jam played. In 2010, a crowd stampede killed 21 people outside the Love Parade, a German dance festival. It'll probably happen again, too.

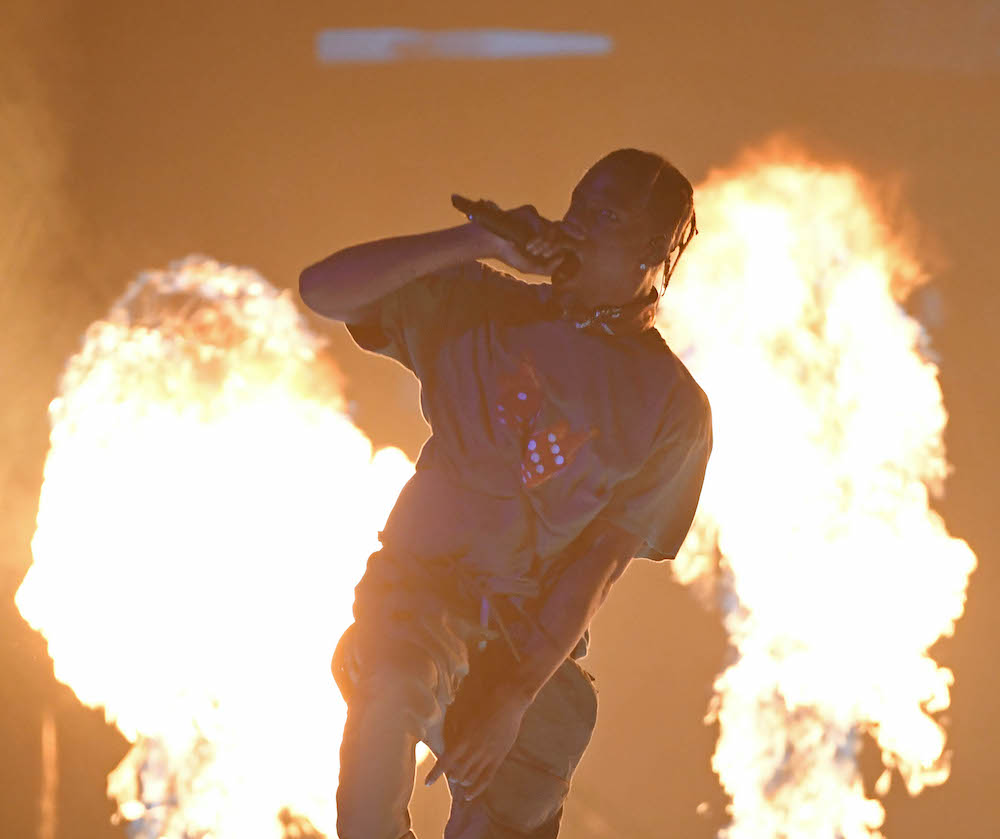

Every detail about the disaster at this past weekend's Astroworld Festival is more disgusting and heartbreaking than the last. Right now, the press and authorities are still hashing out all the details, but the broad contours of what happened at Astroworld seem clear enough. On Friday night, Travis Scott went onstage at the festival that was created in his image. That day, all the other performers played on a different stage, while Scott was the only performer on his own stage, a custom-built "Utopia Mountain" that reportedly cost $5 million to build. Half an hour before Scott's set started, the screens nearby started counting down the minutes until he came onstage. Before Scott even started performing, vast numbers of people pushed their way forward, compacting too many people into too small a space. People fell down. Other people fell on top of those people. The show continued. By the time it was over, eight people were dead, and many more were seriously injured.

All of the individual stories are desperately sad. Among the dead, the two youngest were high school kids, ages 14 and 16. The oldest victim was a 27-year-old man who reportedly died while trying to save his fiancée. One of the people who was hospitalized is 10 years old. Videos from the festival are utterly harrowing. Eyewitness accounts posted on social media over the weekend are even worse. It sounds like complete hell -- people trying to scream for help over the music, people pinned in so tightly that they couldn't breathe, festival staff telling people to stop bothering them, metal barriers and plastic flooring becoming deathtraps.

https://twitter.com/Ashmelym/status/1457001681376452608

If you've been to enough big music festivals, then odds are that none of this is terribly surprising. In its largest form, the American music festival can be a dehumanizing experience. People spend hours waiting to get in, moving from checkpoint to checkpoint, feeling like cattle. Everything, including water, is overwhelmingly expensive. Crowds are vast, and cell-phone reception is often spotty. If you get separated from your friends, trying to find them can become an all-day odyssey. Drugs are plentiful, but conditions are uncomfortable, so drug experiences can go sideways in a hurry. People get impatient. Confusion reigns. Sometimes, despite all that, you can end up having a transcendent experience. Sometimes, you can walk away dazed and exhausted, promising yourself that you'll never spend your time and money on anything like that again.

As a performer, Travis Scott has always gone for grand-scale catharsis. That's his trademark, and that's probably the main thing that got him to the point where he could headline his own festival in the first place. The first time I saw Travis Scott live, it was seven and a half years ago, and he only had a couple of mixtapes out. When I watched Scott at the FADER Fort during SXSW, I remember being weirded out that he didn't really rap onstage. He just shouted over his own record. The music itself was almost beside the point. Instead, Scott spent most of the set running around in the crowd, or teetering up on the barricade, instructing the audience on how to get wild. He came off less as a rapper, more as his own hypeman. It worked. The audience got wild. I didn't know it at the time, but I was looking at the future of live rap performance.

Since that time, Travis Scott has become an arena conqueror and a chart mainstay. A lot of that rise is down to branding. Scott has presented a corporate-friendly face for the recent wave of trap music. McDonald's isn't exactly rushing to give Gucci Mane a Happy Meal, but that company will stamp Travis Scott's face all over its marketing, and Scott will get paid handsomely to let them do it. Some of that rise is simply down to the fact that Travis Scott has some bangers. And some of it is because of that sense of all-out abandon that he brings to his live shows. Moshpits at rap shows existed before Travis Scott, but Scott made them a selling point. Things are supposed to get crazy at Travis Scott shows. That's why people go. In recent years, a lot of other people have tried to create that same feeling of mass catharsis, but Scott, more than anyone else, has made it an integral part of his whole persona.

This has led to problems before. Scott has been arrested twice for calling for fans at his performances to rush barricades. Both times, he's pleaded down to public disorder. In 2017, someone was paralyzed after falling -- or, he says, getting pushed -- from a third-floor balcony at a Scott show at Terminal 5. Scott has talked about being happy when his fans overwhelm security, and his 2019 Netflix documentary Look Mom, I Can Fly shows his live-show managers preparing security for situations that sound a whole lot like what happened at Astroworld last weekend.

In Travis Scott's 2019 documentary, a show manager casually warns the security team of expected danger at the concert:

— The Recount (@therecount) November 8, 2021

"A lot of kids just trying to get out, get to safety because they can't breathe, because it's so compact." pic.twitter.com/BWDy37ozWB

People have been quick to blame Travis Scott for what happened on Friday. The optics are terrible. There's video of Travis Scott, seeing an ambulance out in the crowd, briefly pausing his show, asking if everyone is OK, and then starting it up again. There's video of Scott talking to people off to the side of the stage and then continuing. There are videos of Scott singing onstage a few yards away from people who are passed out. There's also, to be fair, at least one video of Scott pausing his show and trying to get security to help someone who'd passed out.

Travis Scott noticed someone passed out at his #ASTROFEST and attempted to direct security to help them. pic.twitter.com/T80OKbC3Ry

— drama (@dramaforthegirl) November 6, 2021

I've also seen a lot of people online blaming the fans, especially the ones who danced on ambulances, or in front of ambulances, as they tried to get people out. Right now, the Houston police is investigating a claim about someone supposedly running around and sticking people with needles, injecting them with drugs. I heard rumors about that exact same thing when I first started going to festivals almost 30 years ago. Rumors and reports like that serve a clear function. They conjure boogeymen, and then tell convenient stories with those boogeymen. After all, if there was some random force for chaotic evil out in the crowd, then nobody else gets in any trouble.

The characterization of young people at concerts as deranged drug-fueled marauders is nothing new. In a 2011 New Yorker piece about the attempts to stop deadly crowd stampedes, John Seabrook mentions a column that ran in the Chicago Sun-Times after the disaster at the Who show in Cincinnati: "Barbarians... stomped 11 persons to death [after] having numbed their brains on weeds, chemicals, and Southern Comfort." I've seen a lot of tweets in the past few days that look a lot like that.

By that same token, I've seen a lot of commentary about Travis Scott that reminds me of a certain moments in the recent Woodstock '99 documentary. In the movie, festival co-promoter John Scher attempts to blame all the disorder and sexual assault at his festival on the victims of assault and on MTV for covering the show critically. He also tries to pin things on Fred Durst for whipping the crowd up too much. But Sher's the one who booked Limp Bizkit to play and who set up an environment where a Limp Bizkit set could turn into dangerous bedlam. Travis Scott has clearly made a whole lot of bad decisions when it comes to his whole live-show setup, and he looks terrible right now. (There's a grim irony in Scott releasing a new single called "Escape Plan" on the same day as he played this festival where people could not escape.) But Travis Scott didn't kill eight people. I would put that blame elsewhere.

The social-media accounts of the Astroworld festival are pure hearsay, but they paint a compelling picture. I've seen stories about security guards at barricades pushing people back when they tried to escape the crush. I've read about overwhelmed medical personnel who couldn't handle all the people who needed help. Some accounts say that they didn't have enough medical supplies. Some accounts say that they simply had no idea what they were doing -- that they didn't even know how to strap people to gurneys.

I wasn't there, and I can't verify those stories, but those stories definitely resonate with what I've seen at big music festivals. Promoters cut corners. It's what they do. Houston police reportedly tweeted about how "promoters did not plan sufficiently for the large crowds" and then deleted that tweet, posting something instead about how they were working with organizers to determine what had happened. But even if Live Nation and the other companies involved in the show followed the letter of the law in their preparations, it clearly wasn't enough. If they put measures in place to protect people, then those measure failed miserably.

The whole sad story has all sorts of uncomfortable similarities to the Altamont Free Concert, the 1969 Rolling Stones show that stands as the mythical end of '60s idealism. At that show, the Stones hired Hell's Angels to work security, and one of them stabbed 18-year-old Meredith Hunter to death. Three more people died accidental deaths that day. The whole terrible clusterfuck was captured on film in the documentary Gimme Shelter.

Lots of bands played the show, but the festival belonged to the Rolling Stones, and Hunter died while they played "Under My Thumb." By that same token, Astroworld was a whole festival, but the festival was created in Travis Scott's image, and all those people died while he was onstage. As with Altamont, cameras were everywhere; the whole performance streamed live on Apple Music. The images of Travis Scott from Friday night, performing while people were dying, will linger. But there's a big difference between Altamont and Astroworld. Altamont was a free concert. Astroworld happened so that people could make money.

Travis Scott wasn't the person in charge of hiring a medical staff or making sure the venue layout was safe. In an Instagram video that he posted the next day, Scott said, "I could just never imagine the severity of the situation." I'm inclined to believe him. From the stage, the chaos in the crowd at Astroworld probably looked a lot like the chaos that Scott has encouraged at every other show. Scott will certainly need to rethink the way he stages his performances, but a lot of other changes have to happen, too. Those changes need to be structural, and they need to go way beyond one performer telling the audience to "rage." The people who put these festivals together need to think more about the actual experience of the people on the ground. If they don't, then more people will die.

Friday night's show was supposed to be dramatic. Maybe that was for the fans in attendance, and maybe it was for the cameras. That custom-built stage was supposed to be dramatic. So was the countdown leading up to the set's beginning. When Drake came out for a surprise guest appearance, that was supposed to be dramatic, too. But if you're in the crowd, those surprise-guest moments can be absolute hell. When someone famous comes out, people in the back push their way up, and people up front don't have anywhere to go. I don't know if things got worse when Drake came out with Scott, but they definitely didn't get better. According to this Vulture timeline, fire officials called the festival a "mass casualty incident" around 9:30, but police were worried about a riot starting, so they kept the show going for another 40 minutes. Someone should've at least stopped Drake from going out on that stage.

From where I'm sitting, Travis Scott mostly did his job to the best of his abilities on Friday night. He performed the same way he's been performing for years. But the people who planned this festival didn't plan for the kinds of things that happen at a Travis Scott show -- or, if they did, then they laid things out in ways that protected the image of the event, not the people who paid money to be there. I very much doubt whether any of the architects of this fucking carnage will see real consequences for creating this situation where all these people got hurt and died. But everyone involved in planning this festival, and in planning festivals like this one, needs to figure out how to stage big events without treating people like animals. There's no one magical way to prevent travesties like this in the future, but that's one place to start.