Oh You're So Silent Jens and Night Falls Over Kortedala have been reborn as The Cherry Trees Are Still in Blossom and The Linden Trees Are Still in Blossom. A not-so-silent Lekman explains how and why it went down.

Last month, Jens Lekman held a funeral for his most popular album. When 2007's Night Falls Over Kortedala was removed from retailers and streaming platforms on March 21, Lekman marched into an open field near his home base of Gothenberg, Sweden and ceremonially buried the record, a key release in his ascent to hopeless-romantic twee indie-pop royalty. It wasn't the first Lekman classic to be discontinued by his longtime label Secretly Canadian; Oh You're So Silent Jens, a 2005 compilation of early EPs and stray tracks, vanished in 2011.

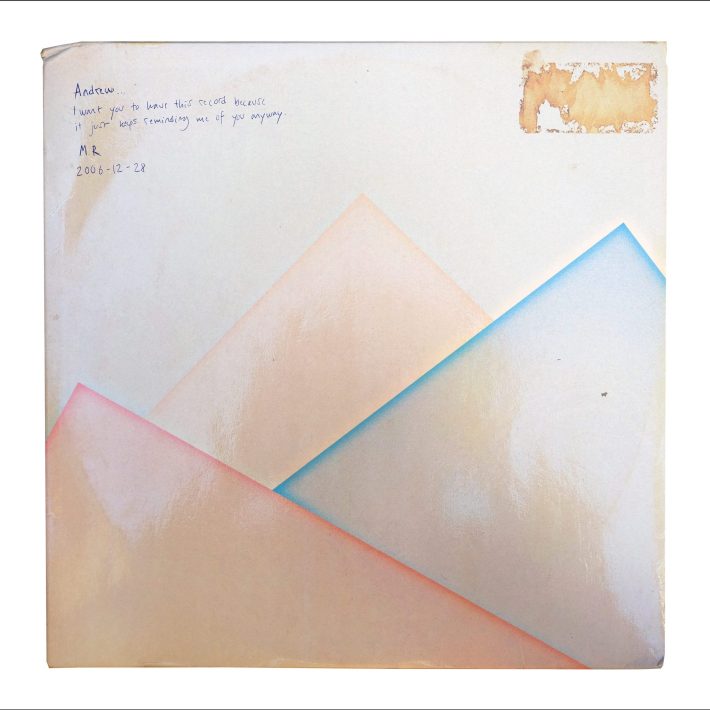

Lekman and his label can now confirm what onlookers have long suspected: The records went away due to legal conflicts over uncleared samples. But rather than let the music remain tucked away in old CD wallets and the dark corners of the internet, Lekman has decided to give it new life. Today he released a partially re-recorded version of Oh You're So Silent Jens under the title The Cherry Trees Are Still In Blossom along with a video for the revamped "Maple Leaves" by directors Jesper Norda and Kristian Berglund. A similarly resurrected Night Falls Over Kortedala will be out on May 4 under the name The Linden Trees Are Still In Blossom. Each of the new LPs features bonus material including "rare, previously unreleased songs, as well as other contemporaneous material such as cassette diaries."

In addition to the pair of transformed LPs, Secretly is publishing two new episodes of its Secretly Society podcast about Lekman and this undertaking. The first of those podcast episodes is out today, and it's well worth a listen, whether for Lekman talking about taking inspiration from Beat Happening and the Avalanches' Since I Left You or discussing the time he created fake live recordings to convince the Secretly Canadian braintrust he was a seasoned performer. Hear it here.

But first, read my recent conversation with Lekman, which touches on the impetus, process, and philosophy behind this project, as well as Lekman's spring tour performing with children's orchestras across North America and other upcoming projects.

When Oh You're So Silent Jens first went away many years ago, streaming was still relatively new. What was your initial reaction to the album disappearing from stores? Did you ever think it would come back?

JENS LEKMAN: That was the thing. Streaming wasn't really a thing back then, and it felt like people were still trading CD-Rs with each other and switching MP3s on Soulseek or whatever. It was sad, it was tragic, but I thought it would live on. And then as the years went by and streaming took over, it was just -- it wasn't even a gap in the discography, it was just gone. And I remember a few years ago, there was a young guy who came up to me after a show and said, "I like that new song you were playing. I think it was called 'Black Cat.' When are you putting that out?" And at some point I realized that these songs have become new again somehow.

I think in some sense that's true for any older music when you're a young person coming and discovering an artist, but I guess it would be especially true if something is just kind of tucked away on YouTube. And that was something I'd wondered about. The music has been on YouTube and probably file sharing, but it's not where people think to look for it. Have you enjoyed at all that you have this release that was somewhat elusive -- this hidden treasure that people have to work to seek out? Or was it more like, no, I want my music to be as available as it could possibly be?

LEKMAN: Well me personally, I think there's a value in some things not being available. I'm not sure if it's because I'm of an older generation or not, but this whole thing that everything is available all the time -- there's something about that that just makes everything feel a bit stale, you know? I'm not against the streaming services or the technology behind that, but there's something about the way we consume music today that makes it feel a bit like a museum. I just always felt like the songs feel a bit like butterflies dipped into chloroform. They're pinned to the wall, but they're also dead somehow. But I mean, it's probably because I'm from an older generation. I think probably the reason why the music feels dead is because of commercialization and the fact that music has to go through these portals, through these gatekeepers like Spotify and so on. I don't think it has do with the fact that it's available. Music can be very alive but still be available everywhere. So I think it has more to do with that.

I kind of agree with what you're saying there. Do you think it has to do with the interface? What makes the current experience so museum-like?

LEKMAN: I think it's just because of these streaming services giving you the illusion that everything is there. You have to be there to exist. I think there are things happening now, I feel like the whole community around Bandcamp and all that, it has grown and changed over the years, but for the last decade it's just felt like you have to be on these platforms in order to exist. And I feel like that takes away any kind of agency from the music. Like you don't exist on your own terms. Because when I was making these records, it was a very different time, and I feel like that time has been forgotten in many ways, or not experienced by people who were too young back then. But the internet was really an anarchy. It was a completely different place. And when you didn't have those internet 2.0 platforms with all the social media and all that as a frame around the work that you've done, you were really able to create your own corner on the internet, in a different way.

Where did the idea to re-record or revamp the albums come from? Is that something you were working on even before you took down Night Falls Over Kortedala, or before you even knew Kortedala would have to come down? Can you give me a timeline?

LEKMAN: I started working on Oh You're So Silent about a year before the pandemic hit. And then during the pandemic it became more and more obvious that Kortedala was also being taken down. So I started working on that simultaneously. So that's the timeline.

Where did you get the idea to bring this music back in this way?

LEKMAN: I had been thinking about it for a few years and I kept thinking that -- every time I entertained the thought it just felt like, "Nah, that can't be done. That shouldn't be done." And then I think it was maybe when that guy came up to me, he said, "I like that new song, 'Black Cat,'" I think that was the moment when I realized, "Hang on a second. It's a little bit sad that these songs aren't available at all." And then as I started working on the youth orchestra tour that I'm doing in May that was supposed to be done two years ago, just when the pandemic hit, there was something about -- because I've always felt like my music should be able to change. It should be emotional somehow, and not something that gets pinned to the wall in a museum. It was something almost provocative in a way that I enjoyed about taking these songs and re-recording them. It was like the question was, "Are you allowed to do this?" And I thought, "Why am I even asking myself that?" I'm still seeing the records not as replacements, really. I see them as portals. I want it to be obvious that these are re-recordings and that you are able to dig and that you're able to go through these portals and experience the original recordings by digging. Because they're still available. It's not like they're going to disappear completely. And I think that they lead to an interesting time in music history.

When you were redoing the songs, were there any unique challenges that you didn't anticipate? Or maybe you did anticipate them and you knew it would be hard going in. What was the hard part?

LEKMAN: Well, the hard part is that I'm a much better musician these days. And a lot of the beauty of those old recordings came from me being an amateur. I'm not a fan of making things sound shitty or making them sound old, adding tape hiss to everything. I'm not a fan of that whole thing. So I didn't want to re-create something and make it sound as lo-fi and amateurish as it was when I was recording those songs. I wanted it to be: If you listen to the old recordings, then you get that part. So I decided that a song like "Maple Leaves," for example, would need to be done in a completely different way.

And so I recorded it with a string quartet. And the inspiration for that came from Joni Mitchell's re-recording of "Both Sides Now" that she did when she was 57, I think. I really wanted to capture something in that song that I've always felt has been there, but from a more mature perspective. I've always loved the way that Joni Mitchell sings, "It's love's illusions I recall/ I really don't know love at all." And how when she sings that when she's 57, it just has a completely different weight. It hits you in a completely different way. And I wanted it to the same with "Maple Leaves," which ends almost the same with "I never understood at all." I think that song, even though it was a song I wrote when I was 21, I still feel like it captures something about love that I'm happy with still today. Love as a misunderstanding, a misheard word. Which is still what I think love is. You'll never know what the other person likes about you, and that person doesn't know why they like you either. We never know why love sparks up or why it dies down. And that's something that I wanted to capture with the new recording of "Maple Leaves."

And then "Black Cab" for example was hard because that song really has this lo-fi feeling in the original that is marvelous in a way, and I just decided to re-record that in the band version that we've done live for the last 15 years. And then I've also done this acoustic version, so I decided to incorporate that too. There were a lot of difficult decisions to be made when I made the recordings, to be sure.

Did you keep the old vocals for these songs, or did you redo them?

LEKMAN: I kept all the old vocals except for "Maple Leaves" and "Black Cab," which had to be recorded from scratch. I had recorded over the four-track recordings for those songs.

After Night Falls Over Kortedala you switched to not using samples anymore. Was that just because you sensed that it was becoming more legally murky, or was it more like, "I want to switch it up, I'm tired of using samples, I want to try something different"? What was the impetus for that?

LEKMAN: Yeah, both. There was a practical reason, but there was also an aesthetic reason. I felt like Night Falls Over Kortedala was every color in the universe at the same time, and that's what I wanted to do with that record. And the songs I wrote after that were mostly inspired by a horrible breakup that I went through, and I felt like they needed something more black and white -- something more minimal, I guess.

And that is what became I Know What Love Isn't?

LEKMAN: Yeah, exactly.

Notably, When I Said I Wanted To Be Your Dog has not been taken away, and you haven't re-recorded that. Why not? Is that a matter of there's no pressure from sample rights holders to take it down? What's the reason there?

LEKMAN: I actually can't answer that question. [laughs]

I was really interested in the story from the podcast about how you created fake live recordings to convince Secretly Canadian that you had played live shows. At what point did they find out the recording was not real and that you had doctored it? Was it a question of months? Years? How did they find out?

LEKMAN: I think they found out because I talked about it in an interview somewhere. But that was years after. I think by then it was too late for them to change their minds. And also I'd become a pretty good live artist by then, so they wouldn't have to worry anyway.

Recently the most famous re-recording project is Taylor Swift going back to re-record her albums, but she's doing it so she can own her master recordings. Is that something you have included in this project? Did you own the masters on the old recordings? Do you own the masters on the new ones? Is that even a part of your thinking on any of this?

LEKMAN: No, not really.

When Kortedala recently was discontinued, you had a memorial service for it. Can you talk about where the idea for that came from and what the experience was like?

LEKMAN: I had a little funeral where I actually went into this field and I buried the record and set up a cross. I don't know, it's been such a long journey and I knew that this was coming, so it wasn't a very emotional thing for me. But it still felt important to have a little ceremony for it.

You mentioned you view these releases as a portal, but also you talk in the podcast about sending the old recording of "Black Cab" to that guy who approached you thinking it was a new song, and he didn't like it that much. What are your feelings about if people like the new stuff better? Do you have a preference for the original versus the revamp? Obviously people have the right to like what they like, but if people tell you they like the new recordings better, what's the emotional makeup of your reaction to that?

LEKMAN: No, that's fine. If they like the old stuff or the new stuff better, that's totally fine with me. I just want the music to be alive and be allowed to change. And it's really what I've been doing live for the last 15, 20 years as well. The songs have changed. They are woven into each other. And I think that's what I want music to be. I was talking to another journalist the other day who was talking about how everything changed when we were able to print records and record music. Before that, music just went from mouth to ear, and then from that person's mouth to another person's ear. I mean, all those lullabies that have been carried on by mothers and fathers throughout the centuries, who knew what they sounded like in the beginning? I mean, there are still records through sheet music and stuff like that.

I don't know, I just always wanted music to be like that, to be allowed to change. And for this tour that I'm doing now with the youth orchestras, I made a book of sheet music with some of my songs, some of my own favorite songs of mine. And I wrote in the book, in the foreword to it, that if you haven't heard these songs before, don't look them up. Just pick up your instrument and play them and see what you make of them. And if you don't like how they sound to you, go write your own songs. Take what you like about them and do something of your own. Because that's how I started writing songs. I heard songs, and I thought, "That's a pretty good song, but it could be even better." And I wrote my own songs. I always got so annoyed with my favorite artists because they almost had it, and I knew exactly how to make those songs better. And that's why I became an artist.

Do you know what you're going to be doing next after these revamped albums and this youth orchestra tour? Do you have another project on the horizon, or is it kind of a blank slate?

LEKMAN: Yeah, I have two albums that I'm working on that are quite different. I can't really say anything about them, but I've been writing a lot during the pandemic. I don't know, it takes a long time for me to finish my projects, but I think one of them is going pretty well and should be finished pretty soon by my standards. So, we'll see.

I guess having these new revamped albums to release kind of gives you a buffer. Not that there's any kind of real deadline unless the label has given you one, but it gives those of us who are looking forward to new music something to listen to.

LEKMAN: I always think about my friends in the Radio Dept. Do you know that band?

Yeah.

LEKMAN: They are almost as slow as I am. No, actually they're slower than me, I think. I think their last album came out in 2016. So when they put out a record I'm going to feel the heat.

THE CHERRY TREES ARE STILL IN BLOSSOM TRACKLIST:

01 "November 27, 2002"

02 "At The Dept. Of Forgotten Songs"

03 "Maple Leaves"

04 "Sky Phenomenon"

05 "Pocketful Of Money"

06 "Black Cab"

07 "Someone To Share My Life With"

08 "December 19, 2002"

09 "Rocky Dennis' Farewell Song To The Blind Girl"

10 "Rocky Dennis In Heaven"

11 "Jens Lekman's Farewell Song To Rocky Dennis"

12 "Julie (RMX)"

13 "April 23, 2003"

14 "I Saw Her In The Anti-War Demonstration

15 "A Sweet Summer’s Night On Hammer Hill

16 "A Man Walks Into A Bar

17 "Another Sweet Summer’s Night On Hammer Hill

18 "F-Word"

19 "The Wrong Hands"

20 "Eureka"

21 "The Cherry Trees Are Still In Blossom"

22 "Black Cab (Acoustic)"

THE LINDEN TREES ARE STILL IN BLOSSOM TRACKLIST:

01 "And I Remember Every Kiss"

02 "Sipping On The Sweet Nectar"

03 "The Opposite Of Hallelujah"

04 "A Postcard To Nina"

05 "Into Eternity"

06 "I'm Leaving You Because I Don't Love You"

07 "If I Could Cry (It Would Feel Like This)"

08 "Your Arms Around Me"

09 "Shirin"

10 "It Was A Strange Time In My Life"

11 "Kanske Är Jag Kär I Dig"

12 "Friday Night At The Drive-In Bingo"

13 "Your Beat Kicks Back Like Death"

14 "Our Last Swim In The Ocean"

15 "A Little Lost"

16 "Radio NRJ"

17 "The Linden Trees Are Still In Blossom"

18 "When I’m Swimming"

TOUR DATES:

04/30 - Los Angeles, CA @ Aratani Theatre

05/02 - San Francisco, CA @ Great American Music Hall

05/05 - Portland, OR @ Aladdin Theater

05/06 - Tacoma, WA @ ALMA

05/07 - Seattle, WA @ Neumos

05/09 - Salt Lake City, UT @ Urban

05/11 - Denver, CO @ Bluebird

05/13 - Milwaukee, WI @ Back Room @ Colectivo

05/14 - Minneapolis, MN @ Cedar

05/16 - Chicago, IL @ Thalia Hall

05/18 - Pittsburgh, PA @ The Warhol

05/20 - Philadelphia, PA @ Union Transfer

05/22 - Brooklyn, NY @ Music Hall Of Williamsburg

05/23 - Brooklyn, NY @ Music Hall Of Williamsburg

05/25 - Washington, DC @ 9:30 Club

The Cherry Trees Are Still In Blossom is out now digitally on Secretly Canadian. The Linden Trees Are Still In Blossom will be out 5/4, also on Secretly Canadian. Both albums will be out physically on 6/3. Pre-orders are available here.