September 25, 1965

- STAYED AT #1:1 Week

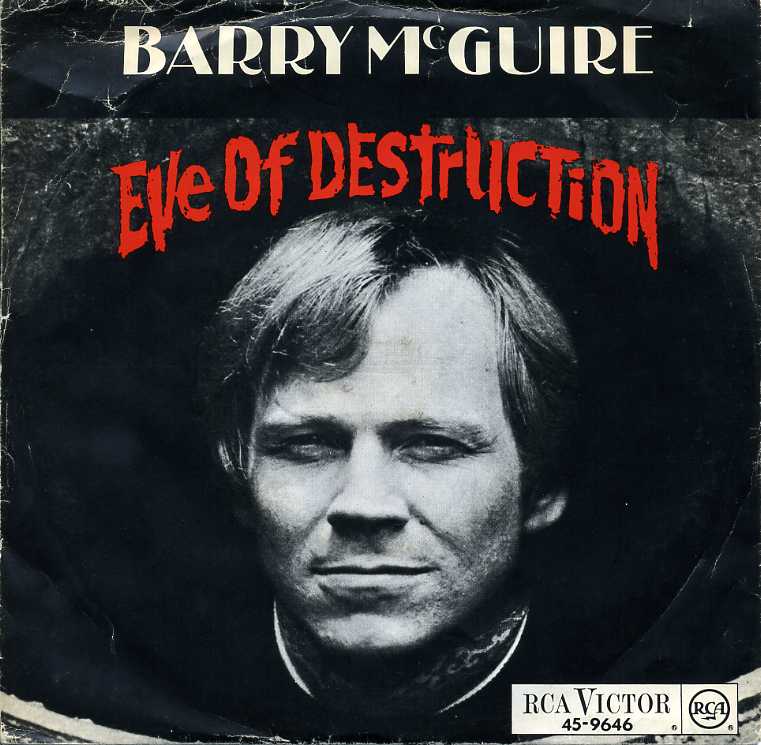

In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

In a lot of ways, the success of "Eve Of Destruction" represents a great awakening. By the fall of 1965, the Vietnam War was looking more and more like a quagmire and the young people of America were looking around and realizing that older generations were happy to send them off to die. Before "Eve Of Destruction," some of the songs that hit #1 made some oblique reference to Vietnam, but they only did it in the form of vague, starry-eyed laments about soldiers away at war (Bobby Vinton's "Mr. Lonely") or the girls at home missing them (the Shirelles' "Soldier Boy"). "Eve Of Destruction," on the other hand, is a pop-cultural reckoning, a lashing-out.

In a strained and raw voice, Barry McGuire surveys a climate where nothing made sense, where it looked like the world was falling apart: "The human world is disintegratin' / This whole crazy world is just too frustratin'." He never mentions Vietnam by name, but the whole song is clearly informed by it. It's directed at the young people who were becoming victims of the war: "You're old enough to kill, but not for votin' / You don't believe in war, what's that gun you're totin'?" (At the time, the voting age was 21; the 26th Amendment changed that in 1971.) The song also extends that lament of cruelty to the Civil Rights struggle in America, something that no #1 song had done explicitly. The song compares "Selma, Alabama" to "all the hate that there is in Red China" and puts forward the idea that "marches alone can't bring integration."

"Eve Of Destruction" isn't exactly a protest song. McGuire never actively calls for change, for marching in the streets. It's more of a world-is-fucked-up song -- a litany of ills, some of them entirely timeless: "Hate your next-door neighbor, but don't forget to say grace." In a world that was changing faster than anyone could comprehend, it's a cathartic venting of grievances.

Looking at the song's context today, though, it's pretty striking to realize that this thing was a pop product the whole time. Songwriter P.F. Sloan was a former sideman for surf-pop stars Jan & Dean and a minor member of the LA session-musician collective who later became known as the Wrecking Crew. (Sloan plays guitar on McGuire's version of "Eve Of Destruction," and Hal Blaine, the Wrecking Crew's ace drummer, also plays.) Sloan had offered "Eve Of Destruction" to the Byrds, who passed. He also offered it to the Turtles, who recorded a lot of the songs that the Byrds rejected. They did record a version of the song, but McGuire's take on it, recorded soon afterward, turned out to be the one that stuck.

Later on, Sloan wrote "Secret Agent Man" for Johnny Rivers and "A Must To Avoid" for Herman's Hermits. Sloan later complained that "Eve Of Destruction" ruined both his career and that of McGuire, but he was a career cog in the pop-music machine. He was trying to wrote hits, and with "Eve Of Destruction," he had one.

McGuire, on the other hand, had come from folk-music circles -- but folk-pop circles, the kind that produced some deeply cheesy early-'60s pop music. Born in Oklahoma and raised in California, McGuire had worked as a commercial fisherman and a pipe-fitter before falling into the coffeehouse scene. Soon enough, he joined the New Christy Minstrels, the folk institution that also helped launch the careers of Kenny Rogers, the Byrds' Gene Clark, and the "Bette Davis Eyes" singer Kim Carnes. McGuire sang on a couple of that group's hits before going solo in 1965. Six years after "Eve Of Destruction," McGuire became a born-again Christian and helped to pioneer the then-underground Christian rock phenomenon.

In any case, both Sloan and McGuire were chasing Bob Dylan, who'd emerged as a ferocious cultural force. In a lot of ways, the entire California folk-rock scene was playing catchup to Dylan, attempting to draft on his momentum. Dylan never sang a #1 hit on his own, but "Eve Of Destruction" is, in a lot of ways, a less elegant rewrite of his 1963 fuck-the-old-people anthem "Masters Of War." These days, "Eve Of Destruction" works more as a historical artifact than it does as a song. As polemic, it's passionate but messy and unfocused. As a pop song, it's raw and snarly, but it never takes flight the way the best pop music of the era did. The best thing about it might be McGuire's voice, a raspy growl that still works as a more conventionally melodic instrument than Dylan's.

People freaked out over "Eve Of Destruction," of course. This was a different era in the American culture wars, one where the repressive forces were presenting themselves as paragons of aggressive normalcy, not attempting to strike badass-biker poses. So the responses to "Eve Of Destruction" are pretty amazing. Consider "Dawn Of Correction," the parodic answer song written and performed by a bunch of East Coast pop songwriters under the name the Spokesmen. It's a point-by-point argument written with the thesis that, look, everything is fine, stop complaining: "The Western world has a common dedication / To keep free people from Red domination / And maybe you can't vote, boy, but man your battle stations / Or there'll be no need for voting in future generations."

GRADE: 6/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's the cover of "Eve Of Destruction" that West Coast punk greats the Dickies released in 1978: