June 28, 1969

- STAYED AT #1:2 Weeks

In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

Whether or not you know Henry Mancini's name, you know a whole lot of the man's music. It's deeply baked into our culture, to the point where it's weird to consider that someone actually had to write this stuff, to pluck it out of nonexistence. For instance: I have never seen one frame of Peter Gunn, the detective show that started airing on CBS in 1958. And yet Mancini's tense twangy-guitars-and-screaming-horns Peter Gunn theme music has been a part of my life for as long as I can remember. That's entirely because of Spy Hunter, the '80s arcade game that turned Mancini's music into indelible 8-bit bloop-pings. I hear any version of that music, and my brain instinctively goes into avoiding-oil-slick mode.

Mancini, born to Italian immigrant parents and raised in a Pennsylvania steel town, studied at Juilliard, served in the Army in World War II, and became a pianist and arranger in the Glenn Miller Orchestra after Miller himself had died in a plane crash during the war. Eight years after starting with the Glenn Miller Orchestra, Mancini earned his first Oscar nomination for scoring the biopic The Glenn Miller Story. He ended up winning four Oscars, as well as 20 Grammys and a few assorted other awards.

Mancini went to work for Universal in 1962, and he ended up scoring more than 100 movies. He did plenty of TV shows, as well. He co-wrote "Moon River" and "The Days Of Wine And Roses." He wrote "Baby Elephant Walk." He wrote the Pink Panther theme. He scored Touch Of Evil and Breakfast At Tiffany's and Charade and Wait Until Dark. He wrote the "viewer mail" music for Late Night With David Letterman. He helped popularize the idea that you could use jazz in a film-score context. Entire sections of your brain have been colonized by the music that Henry Mancini wrote. And yet the one time he scored a freak #1, it wasn't even with music that he'd written.

Franco Zeffirelli's version of Shakespeare's Romeo And Juliet was a hit with young people in 1968, at least in part because Zeffirelli cast characters who looked like those young people. For decades, there was a rumor that Zeffirelli tried to cast Paul McCartney in the movie as Romeo, and McCartney recently confirmed it. But McCartney turned Zeffirelli down, so Zeffirelli instead went with 17-year-old Leonard Whiting and 16-year-old Olivia Hussey. Shakespeare wrote the characters to be teenagers, and in the Zeffirelli movie, Whiting and Hussey radiated the sort of wide-eyed, shaggy-haired idealism that fit well with the era.

The movie resonated. Romeo And Juliet was nominated for the Best Picture Oscar, losing to the musical Oliver! (Night Of The Living Dead, the actual best movie of 1968, was not nominated. Neither were 2001: A Space Odyssey or Rosemary's Baby or Once Upon A Time In The West.) Thom Yorke has said that Zeffirelli's movie inspired Radiohead's "Exit Music (For A Film)." My eighth-grade English teacher showed my class the movie after rhapsodizing about how completely Zeffirelli understood Shakespeare's vision. And at least some of that resonance comes from the movie's romantic, melancholy score. Henry Mancini did not write that score. Instead, the party responsible was the Italian composer Nino Rota, who would earn his true place in film history three years later when he scored The Godfather.

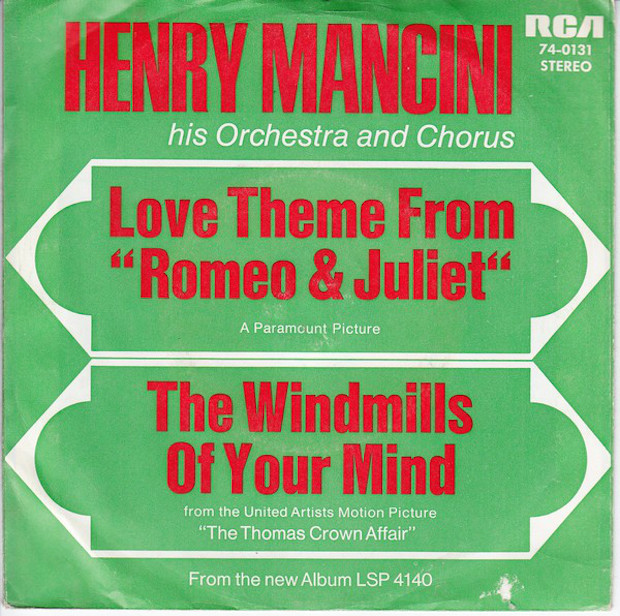

For whatever reason, Nino Rota's version of the score is not the one that sold all those copies in America. Mancini had a side hustle as an easy-listening conductor, and his version of the Romeo And Juliet love theme is grander and less subtle than the one that Rota recorded. On Rota's soundtrack, that music is pretty quiet and simple. It starts out as a mournful English horn, answered back by a harp. When the strings come in, they leave plenty of empty space. Mancini instead plays that central melody on piano, and he surrounds it with strings and drums and strummy guitars and choral wailing.

It's still an affecting piece of music, one that evokes the whole tragic-lost-love idea. It's easy enough to understand why a '60s audience, one that had already been raised on instrumental easy-listening music, would be drawn to a piece of music like that. It's less clear how that piece of music managed to top the charts when the Beatles and Creedence Clearwater Revival and Marvin Gaye were running hot, but I guess that's the '60s for you. Nothing made sense.

GRADE: 5/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's Wu-Tang Clan's 1997 album track "A Better Tomorrow," for which producer RZA sampled Peter Nero's 1969 version of "Love Theme From Romeo And Juliet":

https://youtube.com/watch?v=D73k4Zea59A

(Not counting guest appearances, the highest-charting song from a Wu-Tang member is Method Man's Mary J. Blige collab "I'll Be There For You/You're All I Need To Get By," which peaked at #3 in 1995. It would've been a 9.)

THE NUMBER TWOS: Creedence Clearwater Revival's apocalyptic blues-rock rambler "Bad Moon Rising" peaked at #2 behind "Love Theme From Romeo And Juliet." It's an 8.

THE 10S: Desmond Dekker's reggae masterpiece "Israelites" peaked at #9 behind "Love Theme From Romeo And Juliet. It's a 10.