In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

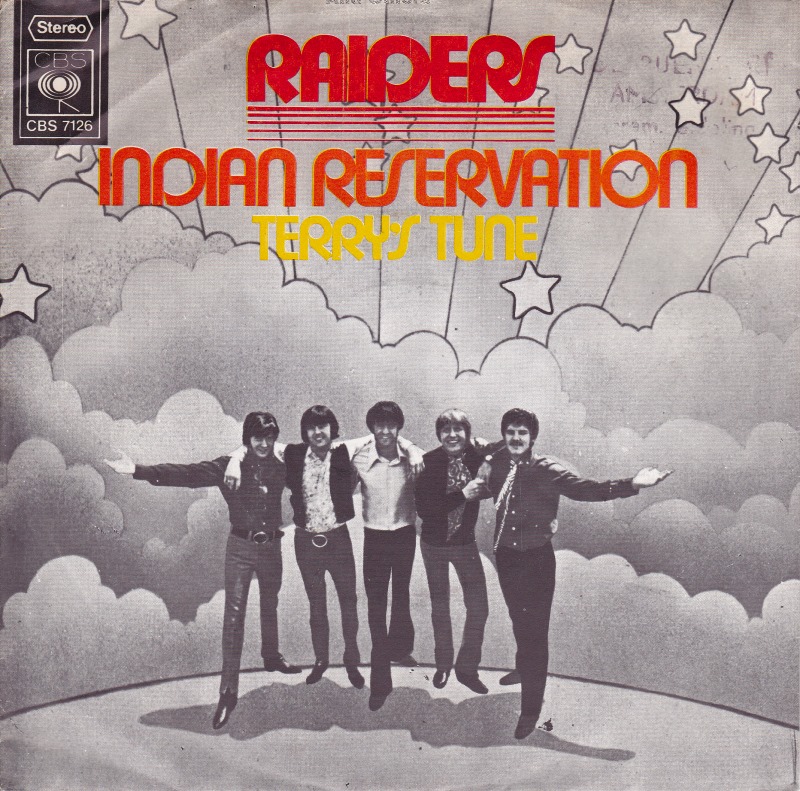

Paul Revere & The Raiders - "Indian Reservation (The Lament Of The Cherokee Reservation Indian)"

HIT #1: July 24, 1971

STAYED AT #1: 1 week

One night in the late '50s, the country and rockabilly songwriter John D. Loudermilk was driving from Nashville to Durham, and his car got stuck in a snowdrift. Loudermilk figured he'd crawl into the backseat, sleep through the night, and get started again in the morning. But in the middle of the night, a group of angry men from the Cherokee tribe pulled Loudermilk from his car. They beat Loudermilk and tortured him, piercing his skin with needles and holding him captive for days. They were going to kill Loudermilk, too, but then Loudermilk told their leader, Chief Bloody Bear Tooth, that he was a songwriter. Loudermilk offered to write a song that would tell the world about the plight of the Cherokee tribe. So Chief Bloody Bear Tooth agreed to let Loudermilk live, and Loudermilk wrote the song he'd promised to write.

This, at least, was the story that Casey Kasem told on a 1971 episode of American Top 40, when Paul Revere & The Raiders' version of Loudermilk's song was taking the world by storm. It was a complete lie. None of it was true. Years later, Loudermilk -- the man who wrote "Tobacco Road" and "Ebony Eyes," and a cousin of troubled country legends the Louvin Brothers -- admitted that he'd made the whole story up. Loudermilk claimed that Kasem had called him at 3AM one night, needing a story to tell about the song. So Loudermilk came up with this ridiculous and racist-as-all-hell tall tale, and the completely credulous Kasem repeated the whole thing on the air.

This story should tell you a few things, and one of those things is this: "Indian Reservation (The Lament Of The Cherokee Reservation Indian)" is not a sincere political screed about Native American genocide. It is pop-music gimmickry, written by a hit-chasing fabulist. The first version of "Indian Reservation" came out in 1959. Loudermilk gave his song to Marvin Rainwater, a country singer who was one quarter Cherokee and who would wear Indian-themed costumes onstage. Rainwater's version of "Indian Reservation," then titled "The Pale Faced Indian," was full of false stereotypes and hiya ho chants. It was not a hit.

In 1968, the British singer Don Fardon, a former member of the mod band the Sorrows, covered "The Pale Faced Indian," changing its title to "Indian Reservation." Fardon's version is a tense blues simmer, and it does away with some of the more egregious stereotypes from the original. And Fardon turned the song into a hit, taking it to #20 on the US charts. Three years later, Paul Revere & The Raiders -- arguably the best band ever to be named after Colonial-era North American colonizers -- got ahold of "Indian Reservation" and took it all the way to the top.

The Raiders had a fun history. Paul Revere Dick (really, that was his name) was a young restaurant owner outside Boise, and he met Mark Lindsay when he was picking up burger buns from the bakery where Lindsay worked. They started up a band, with Lindsay singing and Revere playing keyboards, in 1958, the year before that first version of "Indian Reservation" came out. In 1961, they had a regional hit with a dinky instrumental called "Like, Long Hair." They had to take some time off when Revere was drafted. (He was a conscientious objector, so he worked as a cook.) But when Revere finished up his service in 1962, the Raiders moved to Portland, where they joined a thriving garage rock scene that included bands like the Sonics and the Kingsmen.

The Raiders and the Kingsmen both recorded their versions of the garage-rock standard "Louie Louie" around the same time, but the Kingsmen version was the one that hit. (It peaked at #2, and it's a 10.) The Raiders did not let this get them down, and they ended up being the rare garage band that survived the '60s. Thanks to their name, the Raiders had a gimmick: They dressed up in tricorner hats and frilly shirts. And they had a platform, basically serving as the house band on the Dick Clark-produced variety show Where The Action Is. They showed up on Batman once. They worked it.

But while all this was happening, the Raiders were cranking out some impressively nasty garage rock. "Just Like Me," a #11 hit from 1965, is a legit minor garage classic, a tremulous frustrated snarl nailed to a brick-smashing organ riff and a delightfully primitive guitar solo. And for a couple of years, they bashed out a string of hits that were, more or less, just like "Just Like Me." They were never cool. How could they be, dressing like that? But a lot of those songs have held up better than the work of their more-respected colleagues.

It didn't last. A gimmicky band, even a good gimmmicky band, couldn't keep making hits forever. There was internal drama, too. Half the band quit in 1967, pissed that Mark Lindsay had grabbed control of the band and that session musicians were replacing them on records. Lindsay ventured off on his own and made some solo records. (His 1969 single "Arizona" peaked at #10; it's a 6.) The Raiders, in an effort to seem less childish, dropped the "Paul Revere" from their name. It didn't work. Their singles were still charting, but they'd been effectively banished from the top 10, and it must've been pretty clear that their run was ending.

But then came "Indian Reservation." Jack Gold, the British director of a whole lot of movies that I've never seen, suggested that Lindsay record a version of "Indian Reservation." (Lindsay is one eighth Cherokee.) None of the Raiders play on the recorded version of "Indian Reservation." Lindsay sings on it, but the musicians are all members of the Wrecking Crew. Lindsay, the song's producer, decided to release it under the Raiders name, even if it was effectively a solo single. Revere, who didn't actually have anything to do with the song, knew that he had a hit on his hands, so he promoted the hell out of it. Revere jumped on a motorcycle and drove cross-country, hitting multiple radio stations per day, giving on-air interviews and getting them to play the song. It worked.

Musically, "Indian Reservation" works almost as a last gasp of garage rock. You can hear the band's roots in the nervy and intense riff, imported from the Don Fardon version of the song, and in Lindsay's snarl. But in the shivery strings, you can also hear the distant rumbling echo of the Philly soul and disco that would soon arrive. It's an incredibly strange era-bridging song, a slight overlap of different sounds that exist in the popular imagination as diametric opposites.

But of course, you can't hear "Indian Reservation" on a purely musical level. John D. Loudermilk didn't write "Indian Reservation" as a protest song, but that's how Lindsay sings it. He seethes all through the song, radiating a barely-contained fury. He's singing about something real, of course. In the 19th century, Andrew Jackson forced the Cherokee people, and the people of a number of other tribes, out of their homes in the American Southeast and onto reservations in Oklahoma. Thousands died on the Trail Of Tears, and then the survivors were left to fend for themselves in a new land, the government that had forcibly relocated them doing precious little to help them survive.

In an America that was only just waking up to its own fucked-up history, this new version of "Indian Reservation" hit a nerve. As a mostly-white guy, Lindsay probably did not have the authority to be talking about "though I wear a shirt and tie, I'm still a redman till I die." But it's not like he was doing the cartoonish chanting of the Marvin Rainwater original. He was singing it with conviction, conveying a historical injustice in a way that still worked, more or less, as pop music. It's a clumsy, clueless, well-meaning stab at advocacy, along the lines of the famous "crying Indian" TV commercial, which had started airing the year before. In this busted-ass context, that counts as progress. American pop music had still come a long way in the 11 years since "Running Bear" and "Mr. Custer." Chief Bloody Bear Tooth would be proud.

GRADE: 6/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's London punk band 999's 1981 cover of "Indian Reservation":

https://youtube.com/watch?v=kv9qg-YT2Fg

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Producer 88-Keys sampled "Indian Reservation" for Hodgy Beats' 2016 Busta Rhymes collab "Final Hour." Here's that:

(As a lead artist, Busta Rhymes' two highest-charting singles are the 1999 Janet Jackson collab "What's It Gonna Be?!" and the 2003 Mariah Carey/Flipmode Squad collab "I Know What You Want." Both of them peaked at #3. "What's It Gonna Be?!" is a 6, and "I Know What You Want" is a 7. Busta also rapped on the Pussycat Doll's "Don't Cha," which peaked at #2 in 2005. That's a 4.)