In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

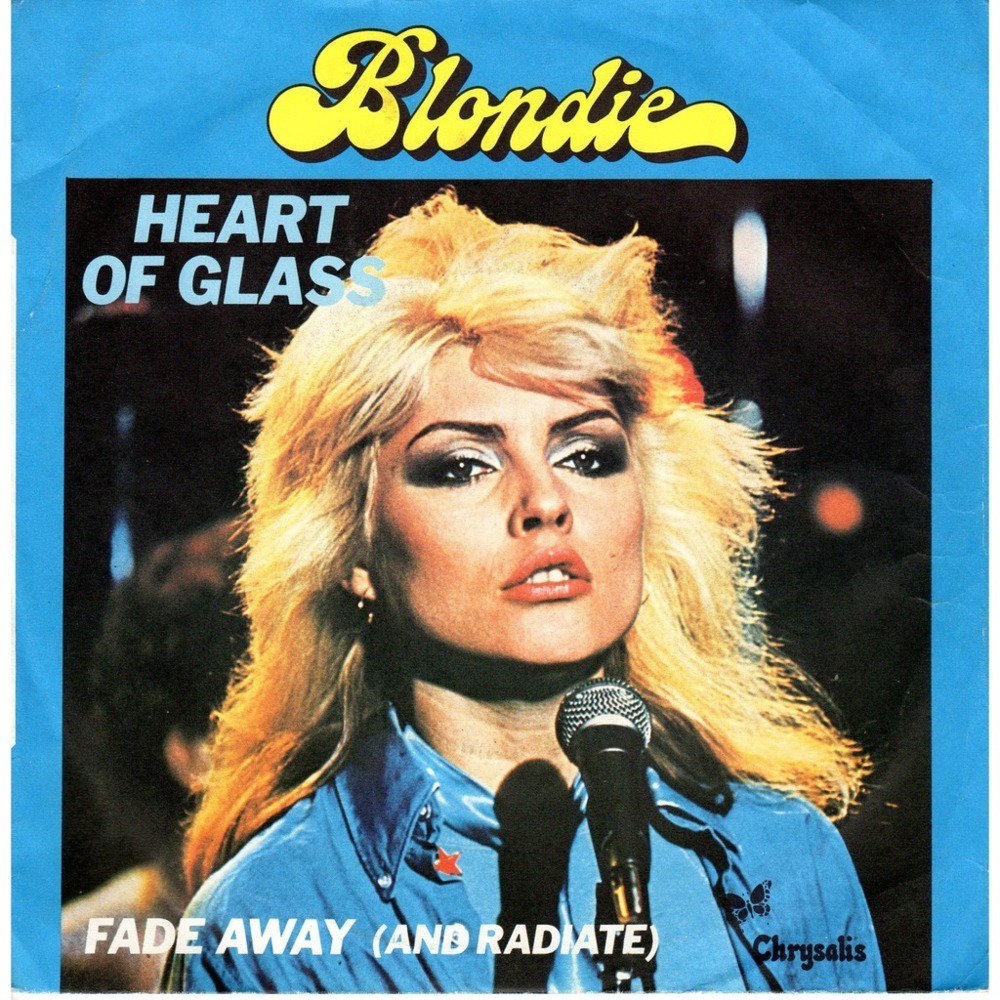

Blondie - "Heart Of Glass"

HIT #1: April 28, 1979

STAYED AT #1: 1 week

It finally happened. Punk crossed over in America. It just had to become disco first.

All through the mid-to-late '70s, the era of disco and soft rock, punk rock had been percolating in Manhattan clubs. But almost none of the acts that came out of that universe ever had much to do with the pop charts. Patti Smith was the outlier; she charted as high as #13 with 1978's "Because The Night," though she needed a Bruce Springsteen co-write to do it. The Ramones' biggest hit, 1977's "Rockaway Beach," only made it to #66. Television, the Heartbreakers, and Richard Hell never charted. The Talking Heads managed one top-10 single over the entire course of their career -- "Burning Down The House," peaked at #9, a 9 -- and it didn't arrive until 1983. These were all acts signed to major labels, cranking out records. It's not that they were trying to avoid the mainstream, exactly. It's more that the mainstream was ignoring them.

In the '70s, America, on the whole, did not have much of a taste for confrontational, bugged-out, intentionally weird rock music. It was different in the UK, where the music press had more power and where less geographical sprawl meant that new sounds and aesthetics could travel outward more quickly. There, punk quickly became pop music, and the New York bands sometimes competed with the homegrown groups on the charts. In America, this stuff simply did not resonate outside its concentrated urbanized cults. In retrospect, it's probably not that shocking that the first punk band to cross over was also the first one to cover Donna Summer at CBGB.

In terms of pure pop-chart dominance, Blondie were so far beyond their New York peers that it's not even a fair comparison. Blondie were the only punk-identified band that even had any real idea of how to be a functioning pop group. Blondie were great stylistic sponges. They could pull a sound out of the air, translate it through their own prism, and make something out of it. They'll appear in this column a bunch of times, and their ability to absorb new pop sounds has everything to do with that. They're the punk band who listened to the radio and liked what they heard. That was a rare thing.

That adaptability wasn't an innate thing for Blondie; it took them time to get there. Debbie Harry, the band's frontwoman, was well into her thirties by the time Blondie landed their first #1. She'd been adopted as a baby, raised in New Jersey by a couple who ran a gift shop. In the '60s, after she got out of high school, she moved to New York and worked as a secretary, a go-go dancer, and a Playboy Bunny. For a little while, she sang backup for the Wind In The Willows, a folk-rock group that released one album on Capitol in 1968.

In the early '70s, Harry joined a band called the Stilettos, and that's where she met the five-years-younger Chris Stein, who would go on to become her long-term boyfriend. Harry and Stein quit that band to form a couple of others -- first the Angel And The Snake, and then Blondie, named after the catcall that Harry would get from truck drivers after she decided to bleach her hair. Blondie fell in with the scene around the bands who played at CBGB and Max's Kansas City, a club where Harry had once worked as a waitress. Their sound was intense but blank, and it was also feverishly hooky. Harry loved the sound of early-'60s girl-group records, and she was able to deliver hooks like that while sounding as fascinatingly blank and bored as Nico. It was a powerful combination.

Still, that combination did not lead to immediate American success. Blondie recorded their first two albums with producer Richard Gottehrer, the former Strangeloves member who had co-written and co-produced early-'60s hits like the Angels' "My Boyfriend's Back" and the McCoys' "Hang On Sloopy." A few of Blondie's early singles went top-10 in places like the UK and Australia. But in the US, none of Blondie's first nine singles even made the Hot 100.

When it came time to record their third album, Terry Ellis, their Chrysalis Records boss, wanted Blondie to make something more commercial, and so he paired them up with producer Mike Chapman, one of the forces behind the early-'70s bubbleglam explosion in the UK. In America, Chapman had just landed two #1 hits, neither of which really sounded anything like Blondie: Exile's "Kiss You All Over" and Nick Gilder's "Hot Child In The City." Chapman liked Blondie's first two albums, but he didn't think they were pushing their sound hard enough. When the band played him their unreleased songs, Chapman's favorite was an untitled, unused demo that had been sitting around for years.

Harry and Stein had written the song that became "Heart Of Glass" together in their West Village apartment in 1975. The song didn't even have a title. They just called it "The Disco Song," since it had partially been inspired by the Hues Corporation's early-disco crossover "Rock The Boat." In its original demo version, though, "Heart Of Glass" doesn't really sound like a disco song. It doesn't sound much like "Heart Of Glass," either. It's a sloppy, sidelong midtempo joint with a slight reggae lilt in the guitars and a bit of a pulse to its beat. Chapman heard potential.

According to everyone involved, Blondie and Chapman had a hell of a time recording "Heart Of Glass." Chapman had a vision for the song, and he wouldn't let the band go until he had achieved it. Chapman found out that Harry and Stein loved Donna Summer and Kraftwerk, and he seized on that, doing everything in his power to transform "Heart Of Glass" into the same sort of hypnotic electronic zone-out. But none of them knew how to make that kind of music, so they all had to figure it out together.

The oscillating, blippy sounds on the "Heart Of Glass" intro come from the Roland CR-78 drum machine, which had only just come out. (Blondie may have been the first rock band to use one.) Blondie drummer Clem Burke played along with the rhythm track, and Chapman, wanting to make sure he got all the sounds right, made Burke record each drum part separately. Years later, Chapman told The Wall Street Journal, "What I was asking Clem to do was close to enslavement, and he was ready to kill me."

Chapman and Blondie also used plenty of other little tricks on "Heart Of Glass": digital reverb, multi-tracked guitars, echo machines, a Minimoog, Chapman's own backing vocals. It's a beautiful piece of recording, all these sticky and hazy interlocking pieces combining together into a sighing, rippling landscape. Parts of it -- Clem Burke's lockstep drums, Nigel Harrison's funky and vaguely Chic-esque bass-pops -- sound truly disco. Other parts sound like rockers in an expensive studio attempting to figure out how the Giorgio Moroder magic was made. The whole thing glimmers and flutters and fades like a mirage on the horizon. It's beautiful.

There's nothing definitively punk about "Heart Of Glass," and many of the people who heard the song probably knew nothing about where Blondie had come from. But "Heart Of Glass" makes for fascinatingly off-kilter disco, mostly because of Debbie Harry's vocals. A whole lot of disco had been built around histrionic, operatic soul-diva vocals. Singers like Gloria Gaynor or Thelma Houston or even Barry Gibb would make lost love sound like personal apocalypse, howling with gutbusting force about their own heartbreak. That's now how Debbie Harry operated.

On "Heart Of Glass," Harry sings about lost love, but she sounds utterly bored with the concept, mentioning this story like it's something she's gotten tired of talking about at parties: "Once I had a love, and it was a gas / Soon turned out to be a pain in the ass." (That had been the original hook; Chapman made them come up with a new title so that the song could get radio play. They still snuck one "ass" in there, though.) The offhandedness was intentional. Harry has said that lots of people just break up and move on; it's not always a big deal. You never hear about those breakups in pop music, but Harry just charismatically shrugged the whole thing off. Her vocals were her version of the girl-group pop that she loved, but she sounds more like an existentialist heroine from a French new-wave film.

"Heart Of Glass" might've been atypical disco, but it ended up working as disco just the same. For years afterward, Blondie talked in interviews about how people were pissed off at them for partaking in disco, and how they'd done it specifically to piss people off. Sometimes, they downplayed it; Stein told Creem that they'd meant the song to be "a novelty item to put more diversity into the album." In the video, they lightly clown the entire idea of disco, with Nigel Harrison checking his hair in a mirror ball. But Harry still makes an icily iconic diva. Her blankness doesn't subvert her glamor; it builds it up.

"Heart Of Glass" was the first Blondie single to chart in the US, and it made stars out of the group. Andy Warhol threw them a party at Studio 54. Harry appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone. Blondie's Parallel Lines album went top-10 and eventually sold more than 20 million copies. And when disco's chokehold over the charts started to fade later in 1979, new wave was right there. So were Blondie.

GRADE: 10/10

BONUS BEATS: The bridge of NORE's 1998 single "Superthug," a song I love deeply, interpolates the "Heart Of Glass" melody. Pharrell Williams, one half of production duo the Neptunes, uses that melody to sing about fly-ass mansions and a million cars in a pinched falsetto. Here's the "Superthug" video:

("Superthug" peaked at #36. NORE's highest-charting single, the 2002 Pharrell collab "Nothin," peaked at #10; it's an 8. Pharrell Williams will eventually appear in this column.)

BONUS BONUS BEATS: On Missy Elliott's 2002 single, producer Timbaland samples the drum-machine intro from "Heart Of Glass." Here's the (incredible) "Work It" video:

("Work It" remains Missy Elliott's highest-charting single. It peaked at #2, and it's a 10. Timbaland will eventually appear in this column.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the opening scene from the 2003 movie Anger Management, a flashback pantsing set to "Heart Of Glass":

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's video of Arcade Fire, with Debbie Harry guesting, covering "Heart Of Glass" while headlining Coachella in 2014:

(Arcade Fire only have one single that charted on the Hot 100: 2013's "Reflektor," which peaked at #99.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's a scene from a 2017 episode of The Handmaid's Tale set to a Philip Glass remix of "Heart Of Glass":

https://youtube.com/watch?v=WHiG5fHHeYs