In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

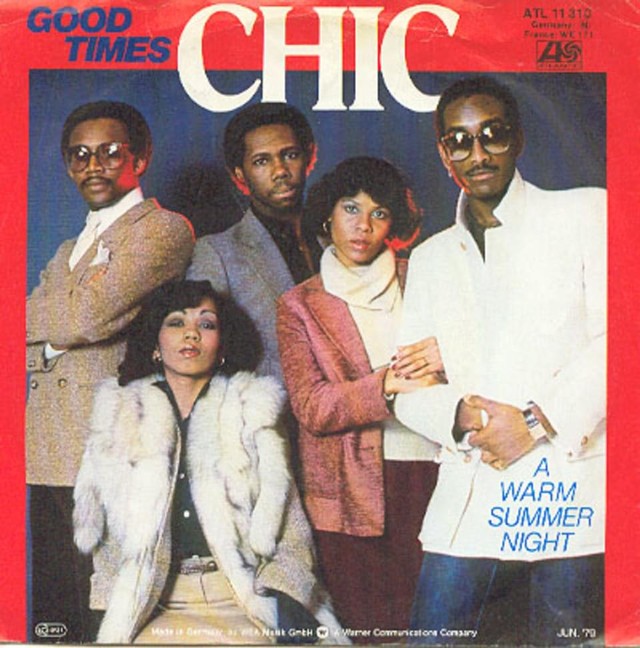

Chic - "Good Times"

HIT #1: August 18, 1979

STAYED AT #1: 1 week

"Here it is, y'all," Nile Rodgers told us. "The song that started hip-hop." This was in the summer of 2000, and Chic were playing a free show at Central Park SummerStage. Rodgers, never Chic's vocalist, still made for a great hypeman throughout the evening, throwing in asides about how everyone used to go off in the clubs to these songs. Halfway though "Good Times," Rodgers even underlined his point about the song, rapping a few bars of the Sugarhill Gang's "Rapper's Delight." Apparently, he now does this every time Chic perform "Good Times."

Rodgers was not, strictly speaking, correct. Hip-hop had been an underground phenomenon in the Bronx and elsewhere in New York for years before Chic recorded "Good Times." It was an underground thing, and the only recorded artifacts are the bootleg tapes of live routines that used to get passed around. The Fatback Band's single "King Tim III (Personality Jock)," generally regarded as the first-ever on-record rap song, came out a couple of months before "Good Times." ("King Time III" peaked at #26 on the R&B chart, but it didn't cross over to the Hot 100.)

"Good Times" was not a hip-hop song. Nile Rodgers and his bandmates didn't know anything about hip-hop. It was off their radar. And yet I know what Nile Rodgers meant when he said what he said about "Good Times." You know it, too. The man has a case. In September of 1979, a few weeks after "Good Times" hit #1, a previously-unknown trio called the Sugarhill Gang released "Rapper's Delight," their first single, on the local indie Sugarhill Records. For 15 minutes, the three members of the group rapped delirious nonsense over the "Good Times," bassline. It wasn't a sample, though they did scratch in some of the strings from Chic's original "Good Times" record. Instead, the Sugarhill Records house band painstakingly recreated the "Good Times" backbeat, playing it over and over.

"Rapper's Delight" was a leftfield sensation, one that people might've regarded as a novelty in 1979. "Rapper's Delight" was a #1 hit in Canada, Spain, and the Netherlands. In the UK, it went as high as #3. All around Europe, it was a smash. In the US, "Rapper's Delight" peaked at #36 -- still pretty good, all things considered. "Rapper's Delight" wasn't the first rap song on record, but it was the first rap hit, and presumably the first rap song that millions of people ever heard. It penetrated the mainstream consciousness, and it started something. 40 years later, rap music is at the center of American popular culture, and it's been there for a long time. Maybe that happens without that "Good Times" bassline. Maybe not.

An amazing thing about "Good Times" is that Nile Rodgers doesn't even need to make vainglorious claims about its place in hip-hop history. "Good Times" is a towering classic, and it would be a towering classic even if the Sugarhill Gang had never happened. "Good Times" is a perfect piece of music, a burbling celebratory stomp that hints at struggle and melancholy while reveling in its own crushed-velvet fabulosity. I've seen people argue that "Good Times" is the final disco #1, the last dance before the backlash truly kicked in. (I'm not sure about that, but we'll talk more about that in future columns.) And that's not even getting into how "Good Times" was also the direct inspiration for at least one song that will appear in this column.

"Good Times" has, thanks in part to "Rapper's Delight," lived on way beyond its all-too-brief pop moment. "Rapper's Delight" is a pop-culture perennial. Nile Rodgers heard it for the first time in a club, freaked out, and threatened to sue Sugarhlll Records. The label avoided that by making Rodgers and Edwards the sole credited songwriters of "Rapper's Delight." This is its own whole saga, since the Sugarhill Gang stole many of the "Rapper's Delight" lyrics from old-school Bronx rapper Grandmaster Caz, the leader of the Cold Crush Brothers, and Caz is still understandably bitter about it today. But that's a whole other story.

"Good Times" has its own story, too. To hear Nile Rodgers tell it, Chic recorded "Good Times" in a take or two, a few hours after he'd written it. Chic bassist Bernard Edwards, Rodgers' longtime creative partner, walked into the studio late, when the band was already working on the track. Rodgers and Edwards had been trying to figure out how to work a walking bassline into one of their songs for a long time, and when Edwards sheepishly strapped on his bass, Rodgers yelled at him to walk. Magic happened.

"Good Times," like "Le Freak" before it, is more groove than song. It kicks off with a sort of jet-engine clang before the groove immediately locks in. In the superior 12" version of the song, that groove then keeps up for the next eight and a half minutes. Edwards' bassline is a masterpiece unto itself. It halts, hiccups, shimmies. It plunges down and then snaps back up again like a yo-yo. Edwards sounds like he's lazily playing with the beat, but he's also pushing it along insistently, nudging it forward into the world.

Everything on "Good Times" feels like it's arranged around that bassline: Rodgers' sparkling guitar-scratch, the staccato string-stabs, the oddly plangent piano. When singers Alfa Anderson and Luci Martin hit the chorus, they almost sound like they're singing along with that bassline. In the extended version of the song, Chic have time to break things down and build it up again, going into a long reverie and then stacking things back up again until the song once again hits peak intensity. But all through that breakdown, the bassline never stops. It's a constant, an old friend.

For all its physical immediacy, though, "Good Times" is a pretty slick piece of writing. It's plainly a party song: "These are the good times! Leave your cares behind!" But Anderson and Martin keep alluding to the "clock on the wall," the constant reminder that these good times are fleeting. They beg us to take advantage, to recognize the finite moment while it's in front of us. Rodgers' lyrics fold in references to Depression-era songs -- Milton Ager's "Happy Days Are Here Again," Al Jolson's "About A Quarter To Nine" -- drawing implicit parallels between that era's party music and the disco of the stagflation-era '70s.

But "Good Times" is simply too much fun to go too deep on seize-the-day philosophy. As on "Le Freak," there's a playfully teasing quality in the way Anderson and Martin's voices mesh. You can hear innuendo in their voices even when there's no real innuendo in the lyrics: "Let's put an end to the stress and strife! I think I wanna live the sporting life!" They make all this sound so damn enticing. I have never roller-skated a day in my life, and yet the line about "clams on the half-shell and roller-skates, roller-skates" sounds like just about the coolest thing in the world.

"Good Times" is everything that anybody could possibly want in a dance song. It's a beautifully constructed, impeccably recorded stomp-vamp, an expert live band working with mechanistic precision and deep-funk intuition at the same damn time. It's got great vocals, great strings, great little instrumental flourishes, a great intro, and an all-time world-historical bassline. It's party music that understands and respects the essential value of partying -- that realizes partying is a necessary moment of catharsis, even and especially when your life is falling apart in every other way. It's a silly song that treats its own silliness with the utmost seriousness. It's wonderful.

"Good Times" would also be the last hit for Chic. They never even appeared in the top 40 after the song hit, though they kept cranking out new records for years. By the early '80s, Chic had essentially become a vanity project. Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards responded to the disco backlash the same way that the Bee Gees did. They became an ace writer/producer team, cranking out big songs for other artists who didn't have the baggage of disco attached to them. As writers and producers, they'll both appear in this column again.

For a while, Chic was simply what Rodgers and Edwards were doing when they weren't making hits for other artists. The group officially broke up in 1983, but they got back together a few years later, dropping another album called Chic-ism in 1992. In 1996, Chic played a series of shows in Japan, and Bernard Edwards suddenly and unexpectedly died of pneumonia the night after they played Budokan in Tokyo. He was 43. Drummer Tony Thompson, the other member of the original trio, lost a battle to kidney cancer in 2003, when he was 48.

And yet Nile Rodgers is keeping Chic going, still playing a ton of shows and festivals. By now, Chic have become the proverbial Susan Lucci of the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame; they've been nominated for induction 11 times without getting in. (In 2017, the Hall Of Fame finally just inducted Rodgers as a producer.) Chic released one guest-star-heavy comeback album in 2018, and they've apparently got another one on the way. Nile Rodgers, as far as I'm concerned, can keep doing that for as long as he wants. Even without all those amazing songs that he wrote and produced in the post-disco years -- even if he'd never written or recorded anything other than "Le Freak" and "Good Times" -- he'd still be a legend.

GRADE: 10/10

BONUS BEATS: What am I even supposed to put here? This entire column is a "Good Times" bonus beat. Hell, the entire past 40 years of American popular music are a "Good Times" bonus beat. "Good Times" is, of course, an iconic and frequently-recurring rap sample source; just last year, Stereogum published a Nate Patrin column on "Good Times" samples throughout the years. Even just the scratched-in title phrase -- "good times!" -- has been scratched into dozens, maybe hundreds, of rap records over the years. But what the hell, let's go with "Rapper's Delight." Here it is, y'all: