I don't remember where I was the first time I heard the Lox's "Money, Power & Respect," but I remember the feeling. The song was good -- hard New York shit from the guys on the "Benjamins" remix, all of them rapping just behind the beat and coming up with cool little catchphrases. It had strings and pianos and Lil Kim on the hook. And then it had that ending. A dog barks, and a new voice comes in -- hoarse, gruff, shadowy. "This is a beat that I can freak," he announces, and then he freaks it. That voice growls on a low boil for maybe 20 seconds, and then something changes. The voice gets more angry, more defiant, and it starts talking some wild shit: "This ain't no fuckin' game! You think I'm playin'? Till you layin' somewhere in a junkyard decayin'? Moms at home prayin' that you coming home, but you not! You sittin' up in a trunk and startin' to rot! And hell is hot! Because I'm here now, baby! It's going down, baby! Get the four-pound, baby!" Hearing that made me feel like I had electricity in my blood. I could've jumped off a building to that. I could still jump off a building to that.

The voice I heard didn't sound like anything else. The owner of that voice had all the fire-eyed passion of Tupac Shakur, who'd only been in the ground a year and a half at that point. It had the throaty scream-rasp intensity of Sticky Fingaz. It had the guttural, demonic pathos of Prodigy. It had something else, too -- a searing magnetism, a rock-star presence. It had charisma and gravity and determination. I wanted to hear more of that voice. I wouldn't have to wait long.

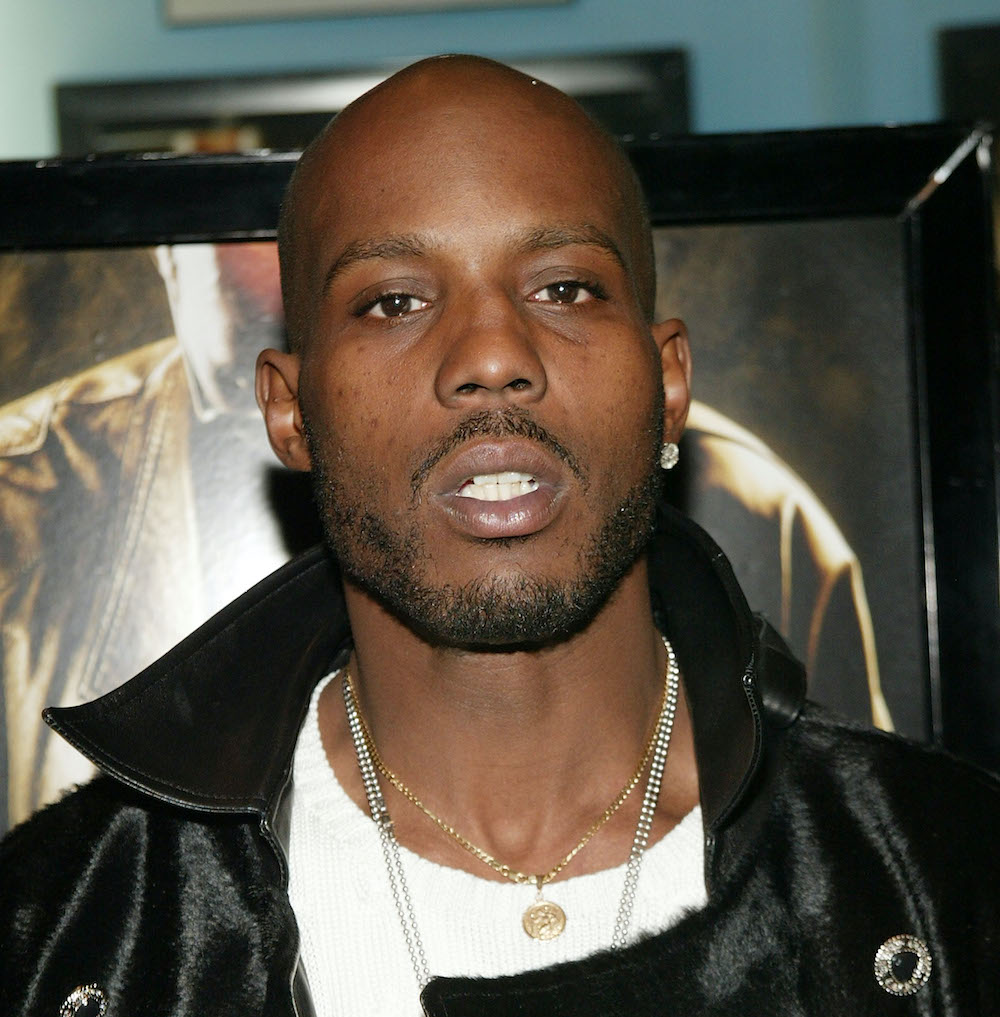

By the time I heard his voice, DMX was 27 years old -- a dark man who had lived a dark life. To even recount the circumstances of Earl Simmons' childhood is to bathe in absurd misery. His real-life trials seem exaggerated, like some Precious Based On The Novel Push By Sapphire shit. The abusive mother who knocked his teeth out with a broom handle and then tricked him into a stay at an institution. The time he got hit and almost killed by a car. The years in and out of group homes and juvenile detention centers. The nights wandering streets, sleeping in Salvation Army donation boxes and befriending stray dogs. The mentor who introduced him to rap and also to crack. If DMX sounded consumed with death, then it's because he just barely skated by with his life, again and again. To make it to 50 was a triumph.

Earl Simmons was a smart kid. He won spelling bees. He loved drawing. When Simmons made music, it was as a beatboxer, not a rapper. (DMX took his name from the Oberheim drum machine that powered the early Run-DMC singles.) As a rapper, though, Simmons found ways to channel things. He rapped in jails. He rapped in crackhouses. He used the torture of solitary confinement to write songs and prayers and songs that worked as prayers. X recorded a demo tape and appeared in The Source's Unsigned Hype column in 1991, long before he'd find fame. (X was one of the first rappers ever to appear in that column; he was Unsigned Hype more than a year before Biggie Smalls.) For years, DMX existed around the periphery of the rap industry. In 1993: a single on the Columbia subsidiary Ruffhouse that didn't go anywhere. In 1995: a spot on Mic Geronimo's "Time To Build" posse cut alongside fellow future stars Jay-Z and Ja Rule. The whole time, DMX was robbing people, stealing cars, going to jail. The whole time, he was also getting better as a rapper.

There's a famous story about a battle between Jay-Z and DMX in a Bronx pool hall late one night, before either one was famous. No footage of the battle has ever been made public. It's all myth, and it's better that way. Dame Dash later said that they battled for hours and that things got tense enough that people pulled out guns. Dash also says that the battle was a tie. X says that he won but that he also learned something from it: "As much energy as I had, I learned that it still had to be controlled." (For his part, Jay-Z says he figured out how to perform while watching DMX; when the two toured together, Jay was getting blown offstage every night.) Another myth: The night Def Jam exec Lyor Cohen ventured up to Yonkers to hear DMX rap. Irv Gotti, a young Def Jam A&R, had demanded that the label sign X, even threatening to quit if his bosses didn't give the rapper a shot. When Cohen met X, X's mouth was wired shut; he'd had his jaw broken in a post-robbery retaliation. Cohen later said that DMX rapped so hard that night that he could hear the wires breaking.

DMX showed up at the exact right time, and he almost immediately became a figure of intense fascination and speculation. With his Def Jam contract in place, X went on a historic run of annihilating other rappers on posse cuts. He'd arrived at the peak of the shiny-suit era, the time when the sheer glitz of Puff Daddy's Bad Boy empire dominated both rap and pop to an extent that we haven't seen since. DMX could've become a Bad Boy artist. Puff passed on signing him, but X still appeared on "Money, Power & Respect" and on Mase's "24 Hours To Live," utterly obliterating both tracks. Still, DMX's mere existence seemed like a rebuke to the slickness of that Bad Boy moment. I remember being baffled that Mase had a guest verse on It's Dark And Hell Is Hot. I had a simplistic understanding of who Mase was and what he represented, and DMX seemed to be the opposite of that. Five years later, 50 Cent would emerge as a sort of insincere, lab-created fusion of Mase and DMX. The two weren't the oppositional forces that I believed them to be.

I was still in high school when It's Dark And Hell Is Hot came out, and there's no way I can properly describe the impact of that album on anyone who wasn't there. It's Dark brought a sudden, screeching end to the shiny-suit era. The feeling in the air changed. The music got harder, uglier. There weren't really any DMX imitators, since nobody could really imitate DMX, though his old buddy Ja Rule definitely adapted some of his strained-roar delivery. But DMX changed the focus. Things got dirtier and grimier and more urgent when he arrived. The Lox, DMX's old Yonkers friends, started up a campaign to get out of their Bad Boy contracts, and they eventually succeeded in joining X on Ruff Ryders. Ruff Ryders quickly became a juggernaut of its own, with the Lox and Eve and Drag-On and with the clanging adrenaline-needle production of Dame Grease and Swizz Beatz. DMX arrived with a whole style already in place -- a look, a feel, and aesthetic. Anyone who's ever driven down North Avenue recognizes what's going on in the "Ruff Ryders Anthem" video. It's Baltimore dirtbike culture, transformed into blockbuster filmmaking.

But It's Dark And Hell Is Hot isn't just the beginning of a movement. It's a masterful rap album, one of the most layered and powerful debuts in the genre's history. DMX might've been a bracing presence on those posse cuts, but It's Dark revealed him to be something more. He was a tormented soul, desperate enough to structure entire songs as conversations with God or Satan. He was a gifted storyteller with a gift for rendering over-the-top violence like he was right there in the middle of it, even when he was imagining himself strapping up with C4 and suicide-bombing an entire police station. He was a craftsman with a sense of how to structure a song, how to half-sing a hook. He was aggressive, but he was also bluesy and gothic and sometimes even tender. In what might've been the album's striking moment, the music dropped out so that DMX could pray. He'd pray onstage every night, too.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=vrEMDFd4SWk&ab_channel=Desusa

DMX could be hard and vulnerable. He could be reverent and violent. To him, there was no contradiction in these tendencies. DMX presented himself as someone who had been through some of the darkest things the world could offer, and who was still going through these things. DMX never had that classic rags-to-riches rap thing. He wasn't Jay-Z, relaxing on a beach somewhere and reminiscing on the wild times that had taken him there. There was no distance. DMX had not come up from struggle. He was the struggle. That's what he showed the world, and the world responded. It's Dark And Hell Is Hot sold five million copies. Lyor Cohen offered X a million-dollar bonus if he could deliver another album in time for the end of 1998, and he did. Flesh Of My Flesh, Blood Of My Blood reached stores in December, giving Christmas record-store shoppers the image of a shirtless DMX covered in blood. That album went straight to #1, too. DMX became the first rapper ever to land two #1 albums in the same year, the first to go platinum twice in the same year.

He didn't let up, either. The same year he released his first two albums, DMX starred in Hype Williams' visually stunning, narratively baffling crime movie Belly. Other than the hypnotic things that Williams did with the camera, DMX was the best thing about Belly. Even though he wasn't yet a dominant star when he filmed the movie, X played a variation on his own persona, and he held the screen just as compellingly as he did in his videos. Belly led DMX to a lucrative side-hustle starring in a series of baffling, hyperactive marital-arts movies for Polish director Andrzej Bartkowiak, sharing the screen with action stars Jet Li and Steven Seagal. The part of Cradle 2 The Grave where X is on the run from police, and he steals an ATV from some extreme sports guys? And then he rides the ATV up some office-building stairs? And then he jumps from rooftop to rooftop, with the extreme sports guys chasing him? That's my shit. I love that.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=VUnmtTTMJrE&ab_channel=MotoMovie

DMX also cranked out five Def Jam albums in quick succession, all of them debuting at #1. He toured arenas -- with Jay-Z, with the Cash Money Millionaires, with Limp Bizkit and Godsmack. His singles never did big chart numbers -- "Party Up," his biggest hit, only reached #27 -- but they were inescapable. It's easy to imagine him racking up #1 hits in the streaming era. X could make explosive anthems, songs that would make you want to punch your best friend in the face, and then he could make solemn, meditative tracks about struggling through life. Sometimes, he could do both. Even his biggest, most crowd-pleasing anthems were drenched in pathos and anger and darkness: "Home of the brave, my home is a cage/ And yo, I'm a slave till my home is the grave." Even the for-the-radio R&B songs were about how he wished women would stop expecting things of him.

For a five-year run, DMX was one of rap's most dominant, magnetic stars. Then it fell apart. The albums gradually became less compelling. The rhetoric got nastier; X devoted much of his 2003 single "Where The Hood At?" to splenetic homophobia. The arrests piled up. X claimed he was retiring from rap, then he moved from Def Jam to Columbia and released a flop album, his first. DMX, married for most of that run, fathered 17 kids by nine women. He declared bankruptcy three times. He was in and out of jail for years, and he was struggling with addiction, too. Five years ago, DMX overdosed in a Ramada Inn parking lot and was revived with Narcan. The struggle came to overwhelm the work.

Through all that, people rooted for DMX. Every time he'd reappear in public -- on Puff Daddy's Bad Boy reunion tour, for instance, or in the Chris Rock movie Top Five -- nobody could look away. If you loved rap music, then you rooted for DMX to pull it together, to return to something resembling his old glory. For a while there, it looked like it was happening. Last year, X took on Snoop Dogg in a Verzuz battle, and it was a total blast to watch these two icons running through their hits, happily praising each other, eating chicken strips and Now & Laters together. DMX signed a new Def Jam deal and got to work on a star-studded album. He apparently finished it, too. I can't wait to hear it.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=RG4TRTbENnE&ab_channel=ChadCaldwell

That ended last week. DMX overdosed again, and he had a heart attack. For days, he hung on, unresponsive in a White Plains hospital. While we waited for news, many of us re-immersed ourselves in DMX's music and thought about the moment that the man arrived and changed everything. Finally, we lost him. On his debut album 23 years ago, DMX spoke to the universe: "Either let me fly or give me death." The universe did both.

Two months ago, DMX was on NORE's Drink Champs podcast, and he told a story about when he was a kid, staying with his grandmother. He'd seen a butterfly, and he loved it. He wanted it. He chased this butterfly into a neighbor's yard, messed up the neighbor's flowers, and caught the butterfly in a jar: "I was happy because I was able to say I caught it, but then it died... I killed the most prettiest thing I'd ever seen in my life because I wanted to keep it for myself. The beauty? That's in the world? Appreciate it. That's it. It's not yours." DMX was not ours. For his entire world-altering run, DMX was a haunted man, living on borrowed time. That, at least in part, is what drew so many of us to him. DMX's death is a real loss, a total gut-punch. But he was strong enough to survive as long as he did, to touch as many people as he could. That's a victory. That's a miracle. Appreciate it.

FURIOUS FIVE

1. LL Cool J - "4, 3, 2, 1" (Feat. Method Man, Redman, Canibus, DMX, & Master P)

2. DMX - "Grand Finale" (Feat. Method Man, Nas, & Ja Rule)

3. Ruff Ryders - "Ride Or Die"

4. Onyx - "Shut 'Em Down" (Feat. DMX)

5. Yung Wun - "Tear It Up" (Feat. DMX, David Banner, & Lil Flip)

IT WAS ALL GOOD JUST A WEEK AGO

My personal favorite DMX moment is watching him fanboy out when meeting Rakim. Look at this energy. pic.twitter.com/yQjC66hCJK

— Lanceadelphia ?? (@LanceAdelphia) April 9, 2021

One summer evening in 2003, I was walking by Lincoln Park High School in Chicago and stumbled upon DMX who was BY HIMSELF racing remote control cars with about 20 kids, having the time of his life. Pure joy. It was a surreal experience. RIP.

— Andrew Barber (@fakeshoredrive) April 9, 2021

Rest In Peace DMX, a true legend. It was truly my honor to work and get to know you. ❤️

— Jet Li 李连杰 (@jetli_official) April 9, 2021

https://twitter.com/DieAnthrDave/status/1380560700133806081