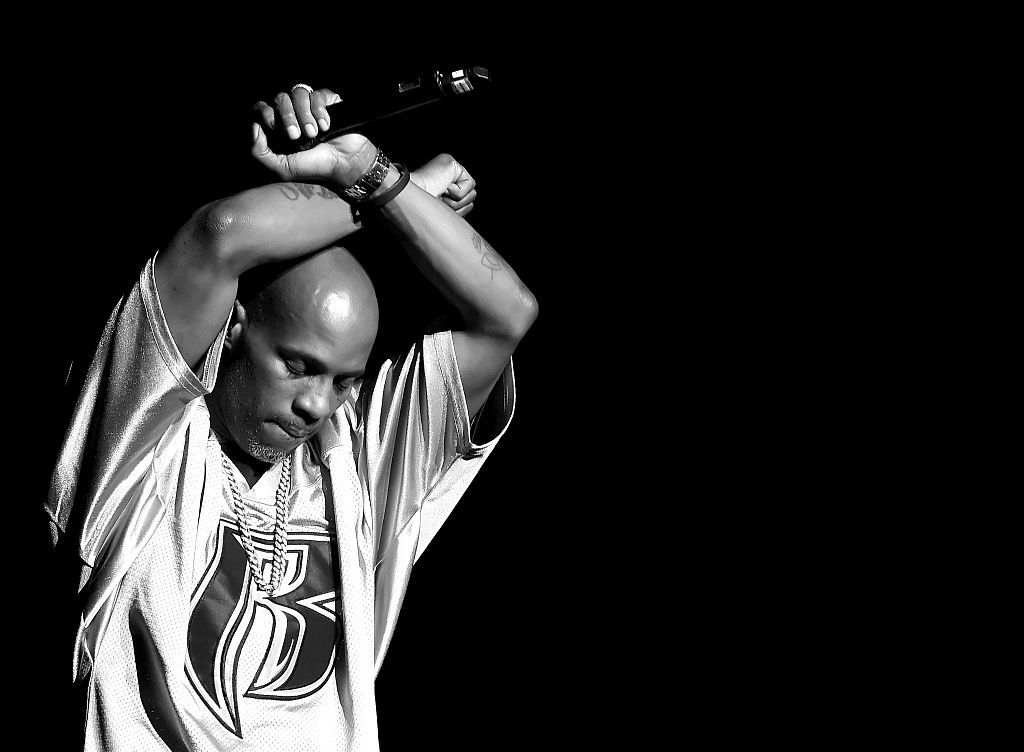

A few weeks before he died, DMX appeared on NORE's Drink Champs podcast and talked about the outlandish list of guests he had lined up to appear on his new album: Bono, Usher, Alicia Keys, Lil Wayne, on and on. He wasn't lying. On Friday, less than two months after DMX's death, his final album Exodus made its way into the world. Only one of the collaborators who DMX named isn't on the LP: Pop Smoke, the ascendant Brooklyn drill star who was murdered a year before DMX died. DMX never met Pop Smoke; the guest verse was something that his people had arranged with Pop Smoke's estate. A posthumous Pop Smoke verse was supposed to appear on DMX's track "Money Money Money," but on the final version of the album, we get young Memphis star Moneybagg Yo instead. That Pop Smoke verse ended up appearing someplace else, so Swizz Beatz had to find a replacement.

Think of it: Representatives for one dead rapper negotiating with representatives for another dead rapper about what would happen with the patched-together beyond-the-grave collaboration that we will never hear. Ever since Tupac Shakur's 1996 murder, posthumous works from dead-before-their-time rappers have done big business. Two of last year's biggest rap albums were after-death efforts from Juice WRLD and Pop Smoke, rappers who were not around to see those albums to completion. In interviews, Swizz Beatz has insisted that DMX finished Exodus before his passing, that the album exists just how X wanted it. (Talking to GQ, Swizz also gave one of the worst album-hyping quotes I've ever seen: "I want the people to take this as an art piece. This is a live NFT. This is a real NFT, by the way -- never forget talent.") But Exodus still sits within a sad, uncomfortable rap lineage.

In the past few years, we've heard a few artists come out with final albums that were clearly understood and intended to be final albums. Works like David Bowie's Blackstar or Leonard Cohen's You Want It Darker were works from dying men who wanted to make final statements and who left around the same time that those statements came out. Exodus is not one of those. DMX's death was sudden and jarring. X had battled depression and addiction for his entire career, but he seemed to be doing better, and Exodus was his comeback attempt, or maybe his attempt at cashing in on decades of goodwill. From all available evidence, the album's guest-heavy structure was Swizz's idea. Swizz wanted to prove to DMX how much the music world loved him.

I don't honestly believe Exodus is coming out in the form that DMX intended. The album feels sketchy, half-finished. DMX himself rarely gives more than one verse per song. Whenever X appears on his own album, he sounds like a guest at a party that's being thrown in his honor. Some of the tracks on Exodus have been around for years. The Jay-Z/Nas collaboration "Bath Salts," for instance, dates back to 2012, when it didn't make the cut on Nas' Life Is Good tracklist. Swizz played the track on a proto-Verzuz 2017 beat battle with Just Blaze, and it features a DMX who sounds significantly different from what we get on the other Exodus tracks. The Bono track "Skyscrapers" was originally intended for a Swizz solo album, and it didn't have DMX on it. As fun as it might be to imagine X and Bono passing a blunt back and forth in the studio, that never happened. The song is merely a relic of past Swizz Beatz Grammy-family schmoozing.

During his lifetime, DMX never released an album with this many guests on it, simply because DMX never schmoozed. A DMX album was a heavy internal trip. X did not interact with the pop world; he forced the pop world to interact with him. (This was somehow the case even when he had Sisqo on one of his biggest hits.) DMX always rapped like he had fire burning in his soul, like he needed to get it out. That style was not conducive to a star-studded affair like Exodus.

It's probably fair to look at Exodus as an outgrowth of Swizz and Timbaland's Verzuz empire. Plans for the album started after X and Snoop Dogg's Verzuz battle last summer, and X recorded much of it in Snoop's Verzuz studio, the site of that battle. DMX first rapped his verse from "That's My Dog," the Lox collab that opens Exodus, during that Verzuz battle. If DMX was alive for its release, Exodus might feel something like a Swizz Beatz brand extension.

In a Verzuz battle, a big-name appearance can be exciting enough to leave an impression.A track like "Bath Salts" could absolutely kill in the context of Swizz's face-off with Just Blaze four years ago, but it doesn't work as well as a regular album track in 2021. (Swizz is still doing this stuff. During his Verzuz rematch with Timbaland over the weekend, Swizz played a new version of "Bath Salts" with an unreleased J. Cole guest verse. It was an exciting moment, but it would be less exciting if I ever went back and listened again.) A DMX/Bono collab is more fun to imagine than to actually hear. DMX was never a starfucker, and if he'd consciously crafted his final album, my bet is that it would've had a whole lot more Drag-On and a whole lot less Usher.

The most compelling parts of Exodus are all the most DMX parts. Tracks like "That's My Dog" or "Hood Blues" follow a familiar late-'90s format: The posse cut where DMX shows up at the end to vomit lava all over everything. 50-year-old DMX couldn't do that the same way that 28-year-old X could, but his teeth-gnashing growl still makes for compelling theater, and he still effectively describes desperation: "I grew up at the dark side, apartheid, where goin' against the grain'll get you kidnapped and hogtied." It's fun to hear classic fired-up DMX ad-libs under the voices of younger artists who never got that kind of encouragement before. And it's also fun how DMX would still be DMX even in the most inappropriate contexts -- like the smooth sex-funk track with the Marvin Gaye sample and the Snoop Dogg guest verse, where X still shows up barking about "gorilla-fuck that ass, leave the pussy sloppy."

The final two tracks on Exodus are almost uncomfortably real, too. The album ends with a live recording of the prayer that X gave during Kanye West's Coachella Sunday Service in 2019. There, DMX sounds ferociously present, vividly alive. He sounds driven, just as he always did when he prayed. Just before that moment, there's a song called "Letter To My Son," and that title is fully literal. X addresses the elegiac, drumless track to the oldest of his 15 kids. It's half apology, half attempted explanation for his own shitty fathering: "I don't know what you thought about my use of drugs/ But it taught you enough to not use them drugs." At the end of the song, DMX asks his kid to call him, and he gives his phone number. Apparently, it was his real phone number, too, though it's since been disconnected. It's almost like that was a private moment. It's almost like we were never supposed to hear it at all.

FURIOUS FIVE

1. Babyface Ray, Payroll Giovanni, & AllStar JR - "Hood Rich"

At this point, I get excited before the Payroll Giovanni verse even starts. I always know he's about to calmly, efficiently rip the track to pieces, and I'm never wrong.

2. OhGeesy - "Get Fly" (Feat. DaBaby)

DaBaby always sounds excited, and OhGeesy always sounds terminally bored. It's an oddly pleasing combination.

3. Rich Boy - "Whole Thang" (Feat. Willa Boy & BWA Kane)

"Throw Some Ds" is the one that everyone remembers, but Rich Boy had a great little run in the late '00s. I don't know if there's about to be a comeback, but this song, at least, is compelling evidence that there could be one.

4. Sleepy Hallow - "Chicken/Mi No Sabe"

I had no idea that I would or could enjoy a Brooklyn drill track built from a sample of a wildly annoying TikTok meme-song. The world finds new ways to surprise me all the time.

5. Larry June - "You Gotta"

Nobody should be able to make a McLovin punchline sound smooth in 2021, and yet here we are.

IT WAS ALL GOOD JUST A WEEK AGO

Future? End of tweet https://t.co/iv5wOECEfV

— James Caan (@James_Caan) May 28, 2021