September 8, 2001

- STAYED AT #1:5 Weeks

In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

The most famous, most widely quoted piece of stand-up comedy of Dave Chappelle's entire career is probably the bit about MTV interviewing Ja Rule on 9/11. The joke comes from For What It's Worth, Chappelle's 2004 Showtime special, and it speaks to the larger point that people need to stop giving a fuck what celebrities say. To illustrate that point, Chappelle remembers the moment, in the wake of the September 11 attacks, when hushed and reverent MTV anchors went on-air with a Ja Rule phone interview. Chappelle doesn't mention anything that Ja might've had to say. Instead, he clowns the idea that Ja Rule would've had anything worthwhile to tell the world on that day: "Who gives a fuck what Ja Rule thinks at a time like this? This is ridiculous! I don't wanna dance! I'm scared to death! I want some answers that Ja Rule might not have right now!"

Dave Chappelle has a point here. Nobody should ever care what celebrities think about anything, and if you want proof of that, look no further than the cancel-culture anti-wokeness ranting bullshit that Chappelle has turned into an entire personal brand in recent years. The line about Ja Rule seems extra-vivid because so many of us remember spending September 11 in front of the TV, rapt and terrified, hoping for any real information. But the news anchors didn't have any useful information, so they kept rehashing the same points again and again, sometimes with celebrity callers chipping in. Donald Trump was on the news that day, too, and the world didn't need to hear his perspective on the day's events any more than we needed to hear what Ja Rule had to say.

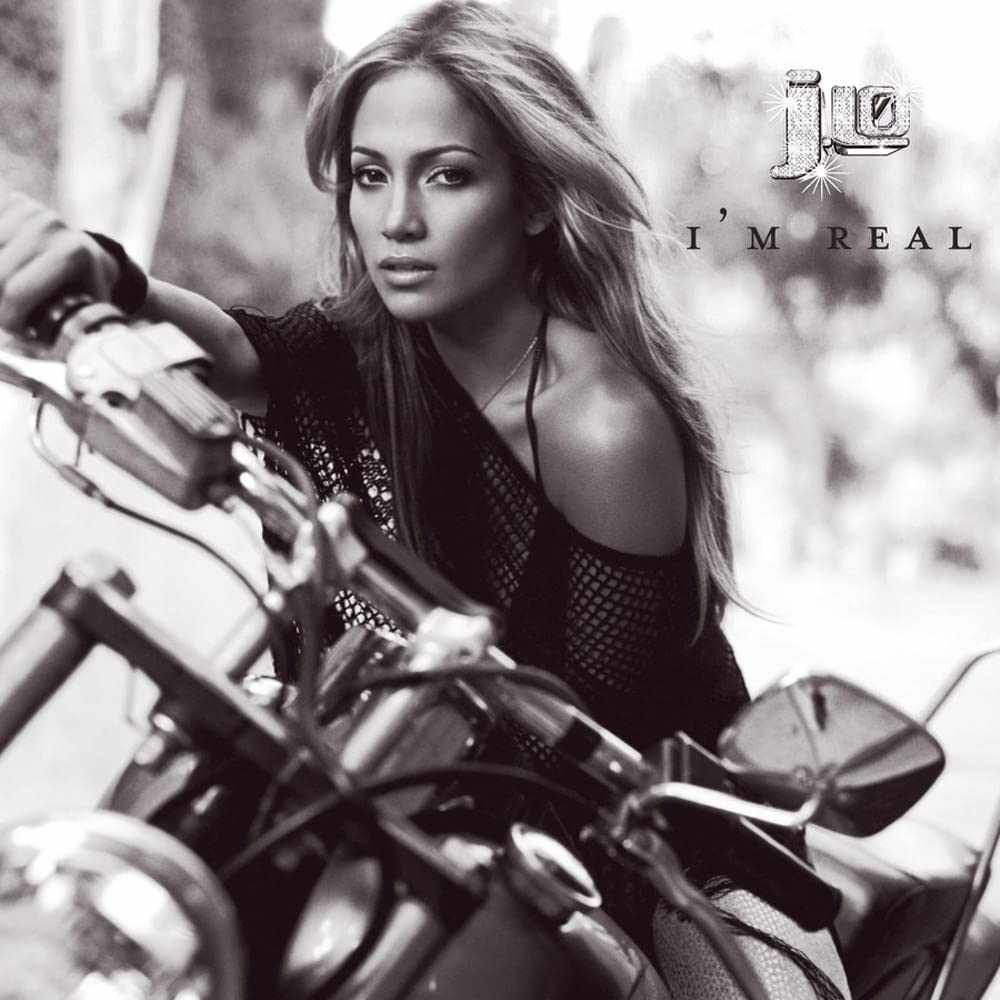

But if the world was ever going to care about Ja Rule's thoughts, it might've been that week. Mere days before the planes hit the towers, Ja Rule began what would become a dominant run of pop chart-toppers. He'd risen quickly through the New York rap world, and he'd only just landed the #1 song in America by bellowing about the way that Jennifer Lopez smells. J.Lo and Ja Rule's duet "I'm Real" is a slight, insubstantial track with a surprising number of subplots in its backstory: the ascent of Murder Inc.'s brand of featherweight street-rap, the changing definition of the word "remix," the long feud between Sony Music boss Tommy Mottola and his ex-wife Mariah Carey, the persistent questions over who gets to use the N-word. But the weirdest, heaviest thing about "I'm Real" is that the song happened to be sitting atop the Hot 100 in the moment when thousands of Americans died and all the rest of us all freaked the fuck out. That, quite frankly, is too much legacy for "I'm Real" to handle.

"I'm Real" did not start off its life as a flirty/guttural Jennifer Lopez/Ja Rule pop-rap duet. Instead, "I'm Real" began as a completely different song. The first "I'm Real" was a dance-pop track with absolutely no relation to the song that eventually topped the Hot 100. It was the first song where Lopez basically served as the primary writer, which would be more impressive if the song had actually been any kind of hit on its own.

In Fred Bronson's Billboard Book Of Number 1 Hits, Lopez's collaborator Cory Rooney, who'd co-written her first chart-topper "If You Had My Love," tells the story. He says Lopez heard the beat that Queens rap producer L.E.S. had made, and she took it into another room to work on some ideas. 15 minutes later, Lopez with the song mostly done: "She had worked out the whole chorus, the 'I'm real, what you get is what you see,' all of that. It was perfect. So I stopped what we were doing and recorded it on tape, so we could capture it while it was hot."

That's a pretty benign pop-song origin story, but in the case of "I'm Real," there's more to it than that. The Sony Music chief Tommy Mottola had signed Jennifer Lopez to Columbia and engineered the whole 1999 Latin-pop boom that helped her make the transition from movie star to pop star. Mottola was Mariah Carey's ex-husband, and Mariah had just departed Columbia. She was about to attempt her own transition, starring in her big movie vehicle Glitter, and she'd signed a huge new deal with Virgin. The persistent story is that Tommy Mottola did everything in his power to undermine Mariah's post-Sony career. Lots of people believe that Columbia sold Destiny's Child's "Bootylicious" as a deep-discounted 49-cent single specifically so that Mottola could block Mariah's Glitter single "Loverboy" from the #1 spot. Lots of people also believe that "Loverboy" sounds the way it does because Jennifer Lopez sample-jacked Mariah.

Maybe Glitter and its soundtrack didn't need any help flopping, but "Bootylicious" did keep "Loverboy" out of the #1 spot; Mariah's song peaked at #2. (It's a 4.) "Loverboy" was originally supposed to be a different song. Mariah and her collaborators had originally built "Loverboy" around a sample of Japanese electronic group Yellow Magic Orchestra's 1978 bleep-bloop dance instrumental "Firecracker," a cover of a song that exotica bandleader Martin Denny had written and released in 1959. (Yellow Magic Orchestra's only Hot 100 hit, 1980's "Computer Game," peaked at #60.) A few weeks after Mariah Carey reached out to clear the sample, the publishers of "Firecracker" got another sample request for a Jennifer Lopez record. L.E.S. had built the "I'm Real" beat from that same frisky, bubbly Yellow Magic Orchestra instrumental.

The original "I'm Real" came out before the Glitter soundtrack was ready, so Mariah Carey and her collaborators had to completely rework "Loverboy," taking out the Yellow Magic Orchestra sample entirely. Instead, they built a new "Loverboy" from a sample of the electro-funk band Cameo's 1986 single "Candy." ("Candy" peaked at #21. Cameo's highest-charting single, 1986's "Word Up!," peaked at #6. It's a 9.) Mariah Carey finally released the original version of "Loverboy," with the "Firecracker" sample on a rarities compilation in 2020, and it really is better than the "Loverboy" that she released in 2001. That doesn't mean it would've been a bigger hit, but it's still something.

So Tommy Mottola viciously torpedoed his ex-wife's single by grabbing the "Firecracker" sample first. That's shady, but it's not illegal or anything. Anyone can sample a track if they're willing to pay for it. The real problem with Jennifer Lopez's original "I'm Real" is that it works better as light corporate espionage than it does as pop music. Lopez's sophomore LP J.Lo came out early in 2001, on the same week that Lopez's deeply forgettable romantic comedy The Wedding Planner hit theaters. The album had a whole lot of hype, and it successfully imposed a new nickname on the star. (Lopez said that she gave that album its title because "J.Lo" was what her fans called her, but I never saw anyone using that nickname before the LP came out.) J.Lo had a whole lot hype, and its first single "Love Don't Cost A Thing" peaked at #3. (It's a 5.)

But Jennifer Lopez was still new to pop stardom, and she had a problem. With her first album, Lopez had gotten a lot of support from R&B radio, and that support was eroding by the time she released J.Lo. At that point, Lopez and Puff Daddy had broken up. Puffy co-produced a few tracks on J.Lo, but those tracks weren't the singles. Lopez followed "Love Don't Cost A Thing" with the single "Play," a straight-up dance-pop single produced by the Scandinavian duo Bag & Arnthor, and that thing got no R&B love whatsoever. "Play" was a relative flop; it peaked at #18. A few months after its release, the J.Lo album had stalled out at platinum.

Jennifer Lopez's original version of "I'm Real" was another straight-up dance-pop track, and she and her collaborators knew that it wouldn't get any play on R&B radio. They had an idea of how to fix that. Cory Rooney had co-written and co-produced "I'm Real," and he'd worked with Puff Daddy back when Puff was still an executive at Uptown Records. There, Puffy had come up with the strategy of remixing R&B tracks and putting rappers on them, and that's what Cory Rooney did with "I'm Real." In the Bronson book, Rooney says, "We did a remake of the song, and I said we have to work with a person that radio cannot refuse, which at the time was Ja Rule."

Ja Rule is about to become a temporary protagonist of this column. Early in the millennium, Ja had the pop charts in a chokehold for a couple of years. So let's get into his whole saga. Jeffrey Atkins came from the working-class Queens neighborhood Hollis. (When Atkins was born, Rhythm Heritage's "Theme From S.W.A.T." was the #1 song in America.) Ja's father wasn't around, and his mother worked in health services. Ja was mostly raised by his grandparents, who were strict Jehovah's Witnesses. As a teenager, Ja became a small-time drug dealer, and he also started a rap group called Cash Money Click with a couple of other Hollis rappers.

Cash Money Click made tracks with a local Hollis producer who called himself DJ Irv and who would later take the name Irv Gotti. The group signed with TVT Records and released the single "4 My Click" in 1995. Soon after, though, Cash Money Click member Chris Black went to prison, and the group lost its TVT deal. They broke up, and Ja Rule went solo. Later in 1995, Ja rapped on Mic Geronimo's "Time To Build," a posse cut that also featured future superstars Jay-Z and DMX. Jay, X, and Ja had plans to start a supergroup called Murder Inc., and all three of them posed together on the cover of XXL in 1999, but the group never happened.

Ja Rule caught a lucky break when his friend Irv Gotti became an A&R guy at Def Jam. Irv helped bring Jay-Z and DMX to the label, and when those guys became stars, Irv got his own Def Jam imprint. He called it Murder Inc., and he signed Ja Rule. In 1998, Irv Gotti co-produced Jay-Z's single "Can I Get A...," and Ja Rule rapped the song's final verse. He gruff roar sounded a whole lot like DMX, to the point where a lot of people thought it was DMX. But Ja's frantic energy really pushed the song that much harder. Ja has never sounded cooler than he did on "Can I Get A...," and he's never looked cooler than he did in the song's video. "Can I Get A..." showed up on the Rush Hour soundtrack, and it became a crossover hit, peaking at #19. Suddenly, Ja Rule had made a name for himself.

In 1999, Ja Rule opened for Jay-Z and DMX on the Hard Knock Life tour, and he released his debut album Venni Vetti Vecci. On that album, Ja basically sold himself a as a clubbier, more pop-friendly version of DMX, who was on fire at the time but whose music was way too abrasive for pop radio. Ja filled that market inefficiency. Venni Vetti Vecci went platinum, and its lead single "Holla Holla" peaked at #35.

Barely a year later, Ja Rule released his sophomore album Rule 3:36. On that album, Ja got more cuddly. He sang more hooks, and he put in more work with R&B singers. Ja himself didn't seem to realize that this was happening; he seemed to believe that he was Tupac reincarnated. But to everyone else, Ja was increasingly known as the cornball singing rapper with the Cookie Monster voice. That persona didn't win Ja too much critical love, but it did lead to a whole lot of pop success. The first single from Rule 3:36 was the Christina Milian collab "Between You And Me," which just missed the top 10, peaking at #11. Shortly afterward, Ja landed his first top-10 hit when the Lil Mo/Vita collab "Put It On Me" peaked at #8. (It's a 4.) Rule 3:36 went triple platinum. If you wanted a song to break through on R&B radio in the summer of 2001, grabbing a Ja Rule guest verse was the obvious move.

When they were figuring out how to push "I'm Real," Cory Rooney and Tommy Mottola met with Irv Gotti and Ja Rule at the Murder Inc. offices. Irv and Ja weren't remotely interested in "I'm Real," so they decided to come up with a completely new song. "I'm Real (Murder Remix)" is not a remix in any real way. It's got a new beat, a new melody, new lyrics. Irv Gotti and fellow Murder Inc. producer 7 Aurelius threw out the Yellow Magic Orchestra sample and instead built a new track by sampling the loping bassline and the whistling flutes from Rick James' 1978 single "Mary Jane." ("Mary Jane" peaked at #41. Rick James' highest-charting single, 1978's "You And I," peaked at #13.)

Ja Rule wrote the lyrics and melody for the "I'm Real" remix. The teenage Murder Inc. signee Ashanti, who will eventually appear in this column, sang Jennifer Lopez's parts in the demo version, and she sang backup on the record. In the Bronson book, Cory Rooney says that he had the idea for Ja to sing the song, rather than just rap it: "They laughed like you wouldn't believe. It took me 15 minutes to get the room focused again because they tried to laugh me out of the room. I said, 'Now that you're finished laughing, I'm serious. If you look at every hit record you've had so far, Ja, it's you singing the choruses, and people have accepted that about you.'" If Ja Rule didn't think of himself as a singing rapper by 2001, then he was really deluded.

There's another element to the whole Ja Rule/Jennifer Lopez connection, too. Mariah Carey had already worked with Ja Rule on a song from the Glitter soundtrack. Mariah's song "If We" features Ja Rule and Nate Dogg. Later on, Irv Gotti reportedly admitted that Tommy Mottola had told him to rip off "If We" when he was making the "I'm Real" remix. I'd dismiss this whole thing as a big conspiracy theory on the part of Mariah Carey fans, but "If We" really does sound a whole lot like the "I'm Real" remix. Mariah wasn't the first singer to work with Ja Rule, and she didn't own the idea of a Ja Rule collab. Nobody did, except, I guess, Ja Rule. People have been ripping each other off all through pop history; it's part of the process. Usually, though, those ripoffs aren't done for specific and vindictive reasons. In any case, Mariah Carey's understandable resentment toward Jennifer Lopez became an enduring meme.

Dave Meyers directed two videos for "I'm Real" -- one for the original track and one for the remix. The original track's video had a bigger budget, but I don't think I ever saw that thing on MTV. The clip for the "I'm Real" remix, shot in a single day, was everywhere. In that video, Jennifer Lopez dresses like a regular human being -- hoop earrings, Adidas, a pink cutoff Juicy Couture tracksuit that apparently helped that company sell a whole lot of clothes. Lopez and Ja Rule work up a silly sort of chemistry; I like the bit where they trade off synchronized dance steps. But whenever J.Lo flashes that movie-star smile, you remember that she's not a regular person. She's Jennifer Lopez.

I feel like I've already written a fucking book about the "I'm Real" remix, and I haven't really talked about whether it works as a song. Maybe that's because the backstory is a whole lot more interesting than the song itself. If the "I'm Real" remix works, it works because of the built-in contrasts. Ja Rule's voice is an atonal baritone snarl, and he starts the track off by demanding, "What's my motherfuckin' naaaame?" J.Lo answers, "R.U.L.E.," but lots of people heard that line as something else: "Are you Ellie?" This is an extremely funny response to a question about what's Ja Rule's motherfuckin' name. Lopez's delivery is a sharp contrast to Ja's shout. She's feather-light, all unstudied treble. Neither of them can really sing, which is pretty funny. Maybe the Ashanti backing vocals are the reason that the song sounds so much like one of the many Ja Rule/Ashanti duets.

The "I'm Real" remix is supposed to be light and fluffy and insubstantial; that's the whole point. J.Lo and Ja spend the song flirting, assuring each other of their devotion. Their characters have been a couple for a while, but they haven't committed to each other, and people have doubted the status of their relationship. But now that they're both successful, they're locked in, and they can't go on without each other. The song has no stakes. It's catchy, and there's a nice sunny quality to that Rick James sample, but it sounds small and tinny. I got sick of it really quick, but it evidently hit some kind of nerve.

There were further complications. On the remix, Jennifer Lopez uses a word that's generally reserved for Black people: "Now people screaming, 'What the deal with you and so and so?'/ I tell them n***as mind their biz, but they don't hear me though." I've lived in New York, and I've heard many people, of many different ethnicities, using that word conversationally. Fat Joe, another Bronx native of Puerto Rican descent, uses that word all the time, and nobody seems to mind. But New York is not the rest of the world, and Jennifer Lopez is not Fat Joe. Enough people were mad about Lopez using the N-word that she had to make a statement about how she didn't mean it in a racist way and how Ja Rule had actually written that line for her. The controversy came and went, and it is not my place to speak on that whole thing. So I won't! Moving on!

Another issue with the "I'm Real" remix was that it's not a remix at all. It's an entirely different song with the same title. Because of Billboard chart rules, anything that was labeled as a remix could count toward Hot 100 placement. When both versions of "I'm Real" got radio play, they counted toward the song's spins. This annoyed chart-watchers, and Billboard immediately changed its rules. After "I'm Real," remixes would count as completely different singles unless they shared a whole lot of elements in common with the original tracks. But I never heard the original "I'm Real," and I heard the remix constantly. I have to imagine that the remix would've reached #1 on its own, but I don't really know. Soon enough, the "I'm Real" remix was added to the J.Lo album, and that album eventually went quadruple platinum. It's Lopez's biggest seller by far.

It would be ridiculous to read too much into the fact that "I'm Real" was the #1 song in America on 9/11, though I guess there's some resonance in two New Yorkers from working-class outer-borough neighborhoods being on top of the charts when New York was attacked. But the pop charts didn't really change too much after 9/11. Clear Channel radio stations put in some ridiculous rules. A few vaguely inspirational songs, like Enrique Iglesias' "Hero" and Whitney Houston's version of "The Star-Spangled Banner," broke into the top 10. But pop music marched on. "I'm Real" stayed on top, trading off the #1 spot with Alicia Keys' "Fallin'" a few times. The world had changed, and Ja Rule might not have had any answers, but people still wanted to party.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

GRADE: 4/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's the Starting Line's weirdly sincere-sounding 2002 pop-punk cover of "I'm Real":

THE 10S: Jagged Edge's weightless, euphoric hookfest "Where The Party At," with its insanely exuberant Nelly guest-verse, peaked at #3 behind "I'm Real." It's a 10 -- not the one with the stem, the one with the rims, the one that seem to make more enemies than friends.

The Number Ones: Twenty Chart-Topping Hits That Reveal The History Of Pop Music is out 11/15 via Hachette Books. You can pre-order it here.