We've Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

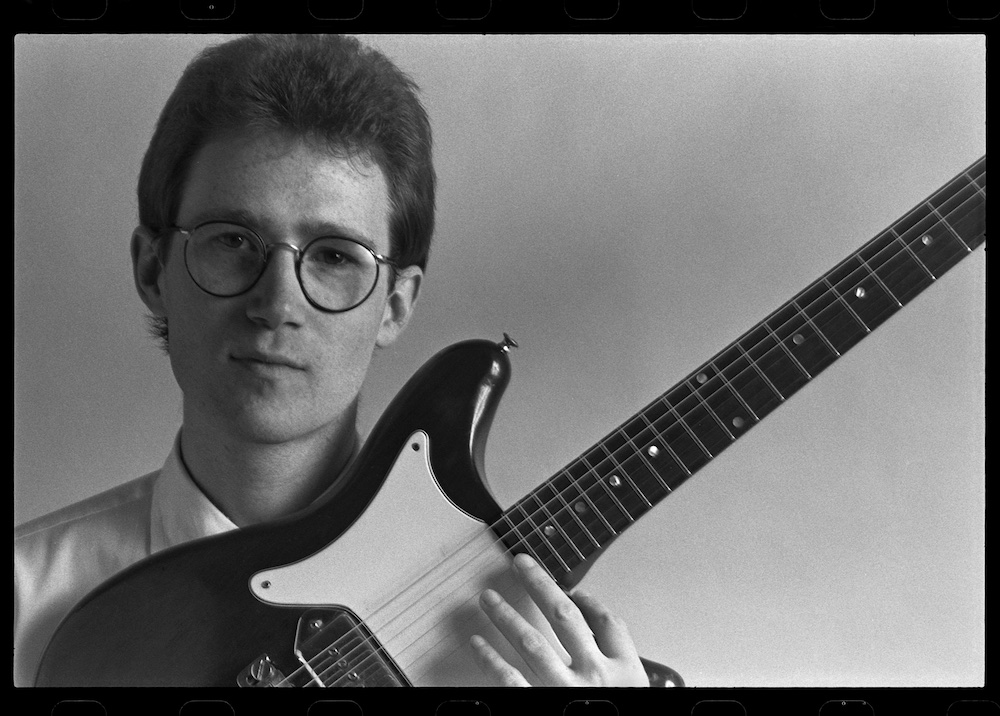

Marshall Crenshaw is one of those if you know, you know artists. An unabashed fan of '50s and '60s jangle-pop and rockabilly, the Detroit-born Crenshaw sold himself as a college-rock/new-wave update to Buddy Holly and even once portrayed the pioneering rocker on film in the 1987 film La Bamba. Signing into our Zoom call from his home in Upstate New York, Crenshaw is not without his own trademark frames (round, tortoise-shell specs from Moscot), a smart-guy aesthetic forever tying him to both Holly and John Lennon, whom he once portrayed in a traveling edition of Beatlemania.

As Robert Christgau once pointed out, 1980s Crenshaw was primarily interested in refashioning midcentury clean-cut rock 'n' roll -- the country-meets-blues scene that birthed everyone from Chuck Berry to Little Richard to Bill Haley And His Comets -- into something that bore a slight punkish New York edge: a little bit '70s Elvis Costello and British Invasion-era Beatles with a CBGB sneer. On his 1982 self-titled debut, home to classics like "Someday, Someway," "Mary Anne," and "There She Goes Again," Crenshaw carved out a spot for himself in a small yet vital pool of nerd-rockers and power-poppers (RIYL: the Feelies, the Cars, Cheap Trick, Nick Lowe, Graham Parker).

In the years since his self-titled debut, which is getting a 40th anniversary reissue this week featuring seven bonus tracks newly remastered audio by engineer Greg Calbi, Crenshaw has released nine more albums (the most recent of which is 2009's Jaggedland). He also spends time with his good friend Robin Wilson of the Gin Blossoms, a seminal '90s jangle-rock band that pointed to Crenshaw as an influence every chance they got. (In 1994, the New York Times spoke to the Gin Blossoms' original vocalist Jesse Valenzuela, who said his band and others that "play in more of a pop-music style all know and love Crenshaw. All those guys have gone to the same rock school, and Crenshaw's one of the 101's.")

Below, critically adored, commercially underrated Crenshaw sits down for a career-spanning interview. We talk about reissuing Marshall Crenshaw, reclaiming the rights to his music, making cameos in La Bamba and Peggy Sue Got Married, feeling "shocked" by S Club 7's cover of "Someday, Someway," and much more.

Marshall Crenshaw 40th Anniversary Expanded Edition (2023)

A 40th anniversary is as good a reason as any to put out an expanded-edition album reissue, but I was curious: I noticed hardly any of your Warner Bros. releases are on streaming services. Is putting out a reissue of your debut a good reason to add it to Spotify, etc, on your terms?

MARSHALL CRENSHAW: Well, I took it off [streaming]. It was on, but what happened with my catalog over the past few years is, I've been able to reclaim the copyrights to the sound recordings myself, back around 2016 thereabouts. I claimed the ownership of the recordings that I did for Razor & Tie records during the '90s and the early 2000s. And I put out self-curated re-releases of those during the last couple of years. And then a couple of years ago, I was able to claim the US copyrights to the sound recordings that I did for Warner Brothers, all my '80s stuff. And so once I had the rights, I went to all the streaming services and asked them to remove everything that was legal to remove at that moment.

There's still one of my Warner Brothers albums out there [1989’s Good Evening], but I'm going to do a whack-a-mole thing on it when I get a chance, when the calendar says that I can.

I wanted to re-release this stuff myself and curate it myself. It's my legacy. I'm curating my legacy, is what I'm doing. I'm doing it myself, as opposed to other people doing it. Why not?

Is the 40th anniversary of Marshall Crenshaw part of that self-curation, or is it a separate project?

CRENSHAW: Well, it just so happens that that nice even number rolled around. The way it works under US copyright law is that once 35 years have passed from the initial copyright date, the author of the work can claim ownership of the copyright if you file your paperwork in a timely manner and do all that stuff. So I did. And now it's five years after that. I guess it took me this long to work it all out, but it's just what the calendar says — oh, it's 40 years — that's got a nice ring to it, 40th anniversary. So the position I'm taking is that these are classic albums and I'm giving them a nice treatment. The 40th anniversary. That sounds distinguished, doesn't it?

How does it sit with you, to revisit work that goes back that far? I mean, I'm sure that these are all songs on the setlist when you perform live. But how does it feel to revisit your debut album as an isolated project 40 years later?

CRENSHAW: There was something emotional about it, the way it hit me. These two albums that are coming out this year — my second album, Field Day, is coming out in July. They represent this really super vibrant moment in my life. They really hit me where I live in so many ways. And the memories attached to those records got really deep to me. To revisit them and look at them, I really loved it, I loved doing it.

I had somebody helping me with the whole thing, who loves the records as much as I do. He grew up with these records and lived with them, and they're part of his psyche. His name's David Gorman. David was also involved in the Rhino reissues of my stuff that came out back in the '90s and 2000s. David worked at Rhino and he worked hand-in-hand on those earlier reissues. He worked with a guy named Gary Stewart, who's no longer walking the earth.

But anyway, it was great to have David along. He was just as enthusiastic this time around as he was last time. And I got a lot of input from him too, just stuff that he thought was important to incorporate into the thing. It was really good to have a partner.

Playing John Lennon In Beatlemania (1978)

During your American Bandstand interview in 1983, you told Dick Clark that performing in a theater setting "didn't really work" for you. And I wondered if you wouldn't mind expanding on that? What did early career Marshall feel about being on Broadway, and why wasn't that the best fit?

CRENSHAW: First of all, it's not my realm. I mean, it certainly wasn't. I loved aspects of it though, because it was exciting. It was a brand-new world, and the theaters themselves were really fantastic places to be.

But anyhow, Beatlemania was an odd fit for me because it did require the mentality of an actor even more than the mentality of a rock musician. And I'm not that person. So a couple times when I was in the show, I got warned that if I didn't try harder, that I was going to get canned. And the first time it happened, the guy who delivered that message was somebody that I didn't like, and he didn't like me. Then I just went about my business for a couple more months, and then I got that same message again, but this time, it was a friend of mine telling me. But I quit the show the next day when he told me that.

The theater itself, it's an art form. I'm not saying it is a bad art form or anything like that. I'm just saying I was like a fish out of water a little bit. They expected you to do the show exactly the same way every time. And that was poison to me, because I'm a rock 'n' roll person. But I did love it. It was a really fun time period in my life.

S Club 7 Covering "Someday, Someway" (2000)

What initially drew you to a rockabilly sound when you were first starting out? What made you want to update it a bit for the ‘80s? Also, I know “Someday, Someway” has been covered many times by many artists, but were you aware that one of those covers came from early aughts TV pop group S Club 7?

CRENSHAW: I did know that, and that shocked me. I thought that was amazing. And a kid in South Africa did a version of it, like on their version of American Idol. He must have got it from S Club 7, I suppose.

As far as my own connection with the '50s rock, that was the music of my childhood. I heard it come into the world as new music. When I was a little kid, all these legendary rock stars like Chuck Berry and Sam Cooke and the Everly Brothers and stuff, they were the pop stars of the moment. And I would see them on The Dick Clark Show or whatever TV show they might be on. I was really riveted to the stuff.

It just drew me in, always. It's what I love. Back then, it wasn't like it is now, where you can just think of anything from any era, any piece of popular music, whether it's from 1915 or from five minutes ago. You can just have it right now in front of you. But when I was a kid, of course, there was no such thing as that. Once something was passed, in three months, it would be forgotten. The culture only moved forward.

All of a sudden, in 1969 — this is when I'm 14, 15 — there started to be a revival of interest in the '50s stuff. And I recognized it — I'm like, yeah, I love this stuff. Where did it all go? Oh, here it is again. I reconnected to it. Also, right around the same time, I started to occasionally enjoy experimenting with psychedelic drugs. And the first couple of times, they really threw me for a loop… I started to love the way music sounded under the influence of these substances. One time, on one of these little weekend [getaway] deals, I heard this old record called “Endless Sleep” by Jody Reynolds. Check that one out if you get a chance.

Even just normally, it sounds like it's liquid or something and it's pouring out at you. Anyway, I just fell in love with this stuff all over again during my late teens, the stuff from my childhood, I rediscovered it. From then on, it was always in my head, and still is.

Performing In Peggy Sue Got Married (1986)

I feel like the late '70s and 1980s were especially obsessed with capturing the '50s and early '60s on film — Peggy Sue Got Married, La Bamba, Back To The Future, even Grease. Have you ever stopped to think about the 20-year nostalgia cycle and the way that wave materialized in the '80s?

CRENSHAW: Well, there's one aspect of '50s nostalgia that I never identified with and still don't. That's a bit where people say it was a simpler time or maybe a better time. That's a lie that people tell themselves, because the world is always like it is now, as far as my life experience goes. It's always a madhouse. The human experience is always full of madness. It was like that in the '50s.

If you really know anything about history in America, you're not going to point to any decade and say, "Oh, that was a simpler time or a better time." There was always turmoil, always. But you get some distance from it and you look back and maybe you were 10 years old and didn't know anything, so you're like, "Oh, it was a better time, it was a simpler time." But anyway, I don't know. I'm affected by it too, the 20-year nostalgia cycle, like you said.

I got to be nearly 20 and I started thinking about my childhood. And then when I was starting to make my own music, a lot of people my age were thinking back to the '50s and '60s because that was their early youth and their childhood. I guess it's just normal human stuff. That's all it is. But the part that I don't like, and I never like, is when people say, "Oh, things were so simple then, or they were better then; it was all fun and games back then, and now it isn't anymore. And I'm mad because it's not anymore." Those are lies.

Another thing people forget about '50s rock is that it was outlaw music. They really got this right in the Elvis movie, the one that just came out: how people viewed rock ‘n’ roll back then. It wasn't like, "Oh, let's go to the malt shop and da, da, da." It was racial tension. It gave the two raised middle fingers to racial taboos, and that was explosive stuff. It still is. Rock ‘n’ roll, that's one of the things I loved about it. It was subversive, and I like that stuff.

Portraying Buddy Holly In The Ritchie Valens Biopic La Bamba (1987)

As a well-documented fan of 1950s rock icons, how was it for you to actually portray Buddy Holly in La Bamba? How do you look back at that experience?

CRENSHAW: At least 50% of the reason that anybody knows my name now is because of La Bamba. So it's a good thing that I did it. When it was first proposed to me, I thought, I don't know, I don't think I should do this. And then smarter people than me talked me into doing it, thank God.

I remember I was in my hotel room the night before we were supposed to shoot the scene, and I was reading the script and I had a cassette tape with some little moments of Buddy Holly talking. I was trying to copy a Texas accent, trying to get into his speaking register. I can't do it. I can't imitate him. But then when we got in the moment and we're doing the scene – I just did it all from instinct and did it my own way, but it worked. This one writer that I really think is a smart guy, a guy named Greil Marcus, said that I portrayed Buddy Holly as a hipster. And I just loved that, that he said that, because Buddy was kind of a hipster.

He really identified with Black culture in a big way. Where he was in his time and place, that was really pushing the envelope. There's stories about him inviting Little Richard to have dinner at his parents' house, and the parents just throwing up their hands in disbelief and him telling his parents, look, if you're not going to be hospitable to [Richard], then you'll never see me again. Who has the balls to do that to their family and say that [in the ‘50s]? But that's the kind of person he really was.

Adding The Diane Warren-Penned "Some Hearts" To Good Evening (1989)

How did Diane Warren's "Some Hearts" – originally written for Belinda Carlisle, later covered by Carrie Underwood – manage to make it onto Good Evening?

CRENSHAW: Let me see, that was my last album for Warner Brothers. That album, to me, illustrates just what a bad job I did of navigating the situation of being in big-time show business. After my second album, I asked to get off the label. I asked them to kick me out of Paradise, but they wouldn't do it. They made me stay and make three more albums. It's probably better that it happened that way. But anyway, the first two are one thing, and then the other three… I'm in a different world now and I'm not high on life the same way that I was on the first two.

It's not to say that there isn't great stuff on all my records because I think there is. With Good Evening, the last one, I didn't even really want to make it, but my accountant insisted that I go make the album. That's the truth. I really struggled. I submitted some songs to Warners that I'd written down in Nashville, and I heard strange stuff back from them about these songs. It was like, "Well, are you going country now?" They didn't say the right things to me, so then I just couldn't write anymore. So about half the album is cover tunes.

We'd go into the studio and it'd be like, "I don't know, what are we going to do today?" One day, the drummer came in and he was really excited. He says, hey man, I ran into Diane Warren last night. I didn't know who Diane Warren was... I didn't know the name. But he said, "She said she's a big fan of yours, and she gave me a song that you can do." So we put the cassette in. I'm like, okay, well, let's do this one.

Then my A&R person in New York, who had signed me in the first place, got really mad at me. She's like, what are you doing this stuff for? She should have understood herself, the situation I was in.

Anyway, my contract expired right after that album came out. They wanted to extend the contract so they could work that track as a single. And I just said, no, I can't take any more. The calendar says I can leave. I'm going to leave right now.

Appearing As A Guitar-Playing Meter Reader On The Adventures Of Pete & Pete (1993)

I’m obviously of the '90s Nickelodeon and Pete & Pete generation, and it was only later in adulthood that I realized how many popular musicians they got to cameo on what was ostensibly a kids’ show. Do you recall how yours came about?

CRENSHAW: Do you remember Syd Straw from the show? She had a recurring role. She was in that episode, I don't remember her character's name but I think she was a teacher.

Well, she's a friend of mine, and that was a thing with the show, like you said, that they would invite people like me to do cameos. She just called up and asked me about doing it. I wasn't busy that day. And I said, sure, great, sounds like fun. So it was that simple, really. It was her calling me. She had probably some kind of conversation with the producers. I don't know whose initial idea it was. But anyhow, we shot it in a residential neighborhood in New Jersey. Danny Tamberelli, he was [Little] Pete, his parents were there. I remember that.

The instrument I had, it was my idea for them to get that instrument for me to play. It's an electric sitar, made in the 1960s. I had rented the instrument previously to work on a track on my third album – the album's called Downtown – and I rented it again for Pete & Pete. It had the same strings on it, really rusty. Anyhow, those are the things that I remember about it. And that it was lots of fun.

And Mark Mulcahy, he wrote all the songs for the series.

I do remember discovering him through Polaris, the band who famously appears in the opening credits.

CRENSHAW: That's right. He had another band after that, that I can't remember the name of. But I really like all the songs on Pete & Pete. They're all his songs, including the one that we did that day in the scene. That show was really treasured by a certain contingent of people.

Co-Writing "'Til I Hear It From You" With The Gin Blossoms (1995)

Around this time last year, I interviewed Robin Wilson from the Gin Blossoms, and he cited you as one of his biggest influences, not to mention a good friend and collaborator. How did the Gin Blossoms end up coming into your life?

CRENSHAW: The first time I ever heard of the Gin Blossoms, I still remember it well. I was in Nashville, and I was at this club called the Exit/In. I'm watching this band called Will & The Bushmen, and they're loud. It's not that big of a place. See if this is a familiar image with you: It's a club, it's young people. The music's ridiculously loud. And you look out into the audience and you see people trying to talk to each other in the midst of this noise. And they're screaming at each other's ears. So not only are they getting slammed by the loud music, but they also have somebody's voice going, right up next to their ears.

It's a crazy thing, but people do it. So I'm standing there watching this band, and suddenly, somebody that I know a little bit starts doing that to me. She's the wife of this attorney that I know. I still know this guy, but they're not together anymore. But anyway, she’s yelling in my ear about this band that she manages in Arizona called the Gin Blossoms. And she says, "They love you. They just think you're the greatest thing walking the earth." And I'm like, oh, that's just great. All I wanted [her] to do was leave me alone. But I said, "I love that. That's so great to hear. Thank you."

And so then she goes, "I'm going to send you their album." It was an album that they put out themselves. They weren't signed to a label. But she did mail it to me, and I liked it. It had some songs, like "Hey Jealousy," on it that ended up on their first album.

So then they were in my head. Now I've heard of the Gin Blossoms. Then maybe a year and a half, two years go by, all of a sudden, they're on the radio. They broke through, and big. So I'm like, wow, good for the Gin Blossoms. I saw one night that they were going to play New York, at Irving Plaza. So I went to the gig and bought a ticket, watched them play.

I didn't go backstage afterwards and introduce myself. I could have done that, for sure. I could have just gone to the guy at the stage door and said, "Tell the Gin Blossoms, Marshall's here." And I could have met them right then, but I didn't. After I saw them play, I left. And then maybe another year goes by and I hear from one of the guys in the band, it's Jesse Valenzuela reaching out to me. He said, "Hey, man, why don't we write a song together?" And by this time, they had a triple-platinum album and all this stuff like that. And I'm like, yeah, okay. Why don't we write a song together? Is it going to be on your next album? Wow, what a great idea. And he says, no, it's going to be in a movie soundtrack. They asked us to do a song in this movie, and we haven't written it yet.

So we got together at SXSW maybe a month or two later. He had started the song already and I helped him finish his part of it, which was the music and the melody and the structure and all that. And then Robin wrote the words but I think he did it at the recording session. I didn't meet him until the record was already out. As soon as it came out, it blew up instantly, it was on the radio immediately. And Jesse invited me to join them at their gig, at the Roseland Ballroom in New York. So I drove down to do that.

And this is true: I was pulling into the garage, parking my car, and I was listening to WNEW. As I was pulling into the garage, the song came on the radio, "'Til I Hear It From You." That was the first time I ever heard it on the radio.

So anyway, I met Robin that night at the gig, and I met the other guys too. And that was it. That's the whole story. I've known him ever since then. We had that amazing experience of that hit song, which really came at a darn good time for me. It was just a wonderful experience. That's when I knew I was in show business. It's just like, they already knew this song was going to be in the movie [Empire Records]. The movie wasn't a hit, but the record was a hit.

Yeah, the movie is now a cult classic. But I know the soundtrack did much better when it was initially released.

CRENSHAW: The soundtrack is good. The music supervisor on the movie was somebody that I knew. At that time, I'd known her since she was a kid. Her name's Karen Glauber. She did a darn good job with that whole thing.

I love those guys. I still do. I was in the hospital about 10, 11 months ago, and I heard from all of them, "get well soon." Even the guys I don't really know that well from the band. And then I saw Robin last week.

Well, I hope you’re doing OK, health-wise.

CRENSHAW: I'm doing great. I just skated through it.

Writing The Theme To Walk Hard (2007)

https://youtube.com/watch?v=2lOW2IjpM-4

I know there’s a 12-year difference between Empire Records and Walk Hard, but did that soundtrack success we just talked about have anything to do with getting you in with more high-profile film projects?

CRENSHAW: Well, possibly, yeah. Because again, the music supervisor wasn't anybody I knew either. But I'm sure that person had it in his head that I'd co-written that song that was in that other movie. And that is part of my identity, isn't it? I mean, my public identity. I was in a couple movies. La Bamba was a really iconic movie, and the other one was too, in its own way, Peggy Sue Got Married, and then the Gin Blossoms thing. The movies have been really good to me over the years.

DJing For WFUV (2011-2017)

You hosted a radio show called The Bottomless Pit for a few years on WFUV. Did you ever see yourself as a radio DJ growing up? How did you want to structure the show and make it your own?

CRENSHAW: Well, I just had a lot of knowledge about popular music. That's one thing my brain seizes on. Anyhow, I was in situations over the years where I'm on a radio show and somebody says, “Why don't you pick the tunes we're going to play?” So I would do it, and I would talk about each one, and I just really loved doing it. It might be partly narcissism too, the sound of your own voice or whatever.

But anyway, I was on The Steve Earle Show on Air America. And he said, come on, bring some of your favorite records and we'll talk about all of them. Then, a short time after that, I ran into this friend of mine who told me that he had gotten a gig as a DJ on Little Steven's Underground Garage [SiriusXM] channel. And I just was like, damn, I want to do it.

So the thing with the radio show is, nobody ever [tells you] anything about what to do with it, and that's the way I like it. The show was a weekly roundup of items from my personal record collection. But I really put thought into it each week. And sometimes, each show would be a little mini-documentary about something. If I had something to say about the music, I would say just whatever context it was in, whatever I had to say about it. It was a great outlet for me to run my mouth and play stuff that I love.

Performing With The Smithereens (2017)

You and the Gin Blossoms' Robin Wilson have been guest frontmen for the Smithereens since the 2017 death of Pat DiNizio. Can you walk me through your history with the Smithereens?

CRENSHAW: I knew them always. I saw them on this show called The Uncle Floyd Show, which is this funny cable show that used to have a lot of rock bands on. Eventually, I met Pat. Pat found me, sought me out, and he and I met. This was before they were even established at all. They were just playing in New Jersey and at this place called Kenny's Castaways in the Village. But I never went to see them. I just saw them on the TV show.

I saw them go through their whole trajectory and everything and all the changes that they went through. Eventually, I did meet the whole band – I met them at a recording session that Pat invited me to. He asked me to play keyboards on a song. And that's where I met the other three guys. I remember them just sitting there looking at me. Pat was the one that I knew. I got to know them over time. I liked all of them a lot.

Then, a little chunk of time went by and I didn't see Pat or any of them so much. Then Pat invited me to be on some tour dates with them. It was a package thing that he put together with myself, them, a guy called Tommy Tutone, and the Romantics. So I did some shows with them, and I went to the first one, and there's Pat and I haven't seen him in maybe 10 years or more. And I see that he's obese. He's turned into this big balloon walking around. And I found that really jarring, disturbing.

I thought, why is he doing this to himself? And I still haven't ever really figured that out… But anyway, I was worried about him. As soon as I saw him again and he was in that state, I knew it was just a matter of time. But then when it really did happen, when I got the news that he had passed away, it still made me sad, even though I knew that he was going to die sooner rather than later. It still felt really bad. To have somebody die like that, that I'd known for so long, and I've had this connection with him…

So anyhow, they did a big tribute show to him, and I got him to be on that. That night, we played together and we all really had a good time with it. Shortly thereafter, I got a call from [drummer] Dennis [Diken] saying, "our fans really want us to continue.” So he asked me to do something with them. It was a TV show. Then, a month and a half later, he calls again [and says], "We're thinking of doing some tour dates." He just asked me [to sing], and I said yes. Then he asked me again, and I said yes. It turned out to be a punk thing that I got to like really quickly. Then I got to know them better and just dug down as people even more than I had already. Now I feel like we're close friends, and I really like talking to Dennis.

I could talk with him about stuff that I can't really talk to that many other people about. We can talk about it in shorthand because we both know everything about what we're talking about – [such as] who played on what record, what studio was this done at. There's so much that we already understand that we can just riff on it really easily. That's fun, because we're both lifelong rock 'n' roll fans.

The other guys too — Mike [Mesaros], the bass player, is really knowledgeable about a lot of things. I jokingly called him the intellectual of the band one time, but there's truth in that because he's a really smart guy. He just knows this stuff that nobody else knows, or nobody else cares to know. They're all really interesting in their own different ways. And so I just keep saying yes. They keep asking me and I keep saying yes. And that's all these years later.

The 40th anniversary expanded edition of Marshall Crenshaw's self-titled debut album will be out 2/17 via Yep Roc.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!