November 13, 2010

- STAYED AT #1:1 Week

In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present. Book Bonus Beat: The Number Ones: Twenty Chart-Topping Hits That Reveal the History of Pop Music.

In February 2011, Kesha embarked on the Get Sleazy tour, her first trip around the world as a headliner. Kesha and her various openers, one of whom will eventually appear in this column, ended every show with a version of someone else's song: the Beastie Boys' 1986 anthem "(You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party)." That's pretty funny. Did Kesha mean it when she sang that song? Did the Beastie Boys mean it when they recorded it in the first place? These are ridiculous questions. They don't deserve answers.

"Fight For Your Right" is one of the stupidest songs in the world, and that's its charm. These days, even the surviving Beastie Boys don't seem entirely certain whether they were mocking or embodying frat-boy clichés on their debut album Licensed To Ill. Maybe they started out doing one thing and ended up doing the other. It doesn't matter. Nobody has ever mistaken "Fight For Your Right," the biggest chart hit of the Beasties' entire legendary career, for a serious song. "Fight For Your Right" is a party song; you can tell by the way the Beastie bellow the word "party" at every opportunity. It's dressed up as a protest song, but that just means that it's a joke about protest songs. ("(You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party)" peaked at #7. It's an 8.)

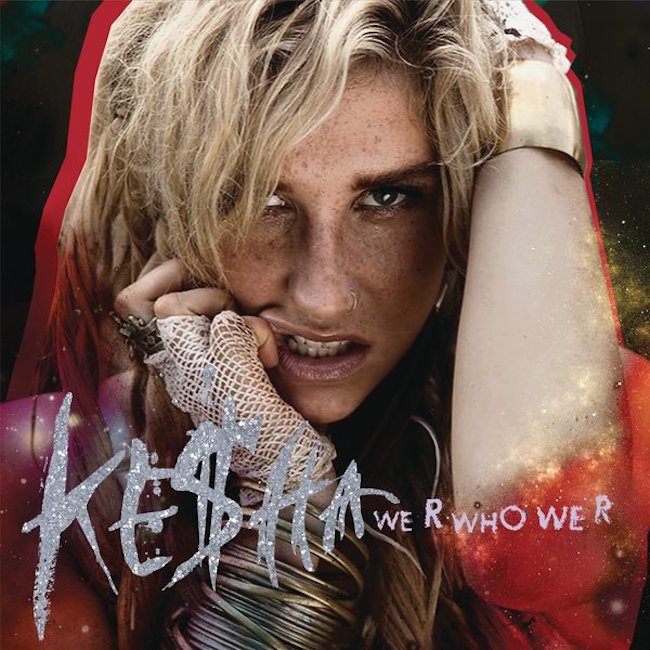

Right before Kesha sang "Fight For Your Right" every night on the Get Sleazy tour, she performed a song of her own -- another one that fell into the overlapping area on the party/protest Venn diagram. This one combined party with protest in different ways. Kesha's "We R Who We R" isn't a joke, though you could've heard it as one. It never directly engaged with standard protest-song dynamics. It didn't even explicitly name the thing that it was protesting. Instead, "We R Who We R" is a party song that communicates its subtext through codes, winks, and nudges. Maybe that's the only way Kesha could come out with a protest song in 2010. Maybe it's the only way a Kesha protest song could've gone to #1.

Actually, "protest song" might be the wrong framing here. Kesha wanted "We R Who We R" to be a song about radical self-acceptance, a queer anthem. She'd already been moving in that direction. When she released the single, Kesha was coming off of the overwhelming success of her debut single "Tik Tok," the first chart-topper and biggest hit of 2010. That song hit a cultural nerve. The day before "Tik Tok" reached #1, Kesha released Animal, a debut album full of garish, sparkly club-pop songs, and she made most of those songs with Dr. Luke and Benny Blanco. The album went triple platinum, and it sent three more singles into the top 10.

The last of the hit Animal singles was "Take It Off," an ode to a place downtown where the freaks all come around. Kesha claimed that she wrote the song after going to a drag show. Maybe it was her version of "Love Shack" -- another song about a queer gathering that's a whole lot of fun whether or not you realize that it's about a queer gathering. ("Take It Off" peaked at #8. It's a 6. The B-52s' 1989 single "Love Shack" peaked at #3. It's a 10.) Kesha came into the game with a cartoonish party-girl persona, and when you do that, you can't exactly pivot straight into serious political messaging. So she did something else. She made her points in interviews, and then she cranked out more of the delirious club-fuel earworms that the market demanded.

Less than a year after Animal, Kesha released her EP Cannibal, a collection of songs that were originally considered for a deluxe edition of Animal. This kind of thing was standard practice in that time -- Lady Gaga's The Fame Monster, Usher's Versus. The EPs weren't supposed to introduce new sounds or ideas, though they sometimes did anyway. (The Fame Monster was a noticeable advancement after The Fame.) Instead, the EPs were supposed to extend these stars' moments and work as delivery mechanisms for more hits.

Kesha had serious matters in mind when she came up with the idea for "We R Who We R," the first single from the Cannibal EP. Kesha told Rolling Stone that she was upset over the surge of queer teenagers who died by suicide, and especially the story of Tyler Clementi, the Rutgers freshman who took his own life after his roommate outed him. "Just know things do get better and you need to celebrate who you are," Kesha said. "Every weird thing about you is beautiful and makes life interesting. Hopefully, the song really captures that emotion of celebrating who you are."

That's a noble sentiment, but "We R Who We R" does not sound like a song driven by noble sentiments. It's a party song. It's about partying. It's about dancing like we're dumb, our bodies going numb, being forever young. The serious stuff in "We R Who We R" is pure implication, like the pause and the emphasis when Kesha quasi-raps about "hittin' on dudes -- hard." When Kesha claims that this song is her attempt to address a whole nation of suicidal queer kids, it reminds me of the whole tradition of Marvel movie directors comparing their work to '70s conspiracy thrillers or European art films. It's like: Sure, buddy. Whatever you need to tell yourself.

But then, what do I know? I'm a straight white guy, and I've never needed to look to a damn Kesha song for any kind of personal validation. And anyway, there's precedent for this kind of thing. Nile Rodgers has said that he wrote "I'm Coming Out" for Diana Ross after going out to a club and seeing drag queens dressed up like Diana Ross. Diana didn't know that she was singing a queer anthem, and when she found out, she thought Rodgers was trying to destroy her career. But Rodgers knew what he was doing. "I'm Coming Out" became a mainstream hit and a queer anthem. The song did exactly what Rodgers wanted. ("I'm Coming Out" peaked at #5. It's a 9.)

"We R Who We R" doesn't really belong to the same tradition as "I'm Coming Out," though the disco and EDM eras have a few obvious things in common. Instead, "We R Who We R" was part of a wave of empowerment anthems that came along in the early '10s. Those songs are more spiritually akin to Christina Aguilera's "Beautiful," the song that -- with apologies to Madonna's "Express Yourself" -- really introduced the language of self-acceptance to the pop charts. ("Beautiful" peaked at #2 in 2002. It's a 10.) "Beautiful" had its dancefloor remixes, but it was more of a tortured ballad. The early-'10s empowerment songs, some of which will appear in this column, wanted to do something else. They wanted to celebrate.

When Kesha talks about "We R Who We R," I think she's being sincere. But Kesha was also working within a restrictive system, and it wouldn't be long before she was at war with that system. "We R Who We R" is also a Dr. Luke track, and there will never be a Dr. Luke track that exists entirely for noble reasons. That would be a contradiction in terms. Kesha co-wrote "We R Who We R" with Luke and with various Luke proteges: Benny Blanco, Joshua "Ammo" Coleman, Jacob "J Kash" Hindlon. (Ammo, from Baltimore, and J Kash, from Virginia Beach, were both new to Luke's orbit. Ammo was literally sleeping in an air mattress on Luke's floor at the time.) Presumably as a result, "We R Who We R" is a whole lot more aggressive in pushing Luke's hooks-above-everything mentality than in its attempts to make the world a more welcoming place.

Before I read that Kesha quote, I don't think it even occurred to me that "We R Who We R" came out of any kind of serious intention. The song does not sound serious, which isn't necessarily a problem. "Tik Tok" isn't a serious song, either, and it's a banger. "We R Who We R" comes off as an attempt to recreate the magic of "Tik Tok," which isn't necessarily a problem, either. It's got the same elements in play: the halfassed cutesy kinda-rapped verses, the brain-obliterating wrecking-ball chorus, the fizzy rave-indebted keyboard stabs, the lyrics about partying into eternity. The problem is that "We R Who We R" doesn't come anywhere near the level of "Tik Tok."

The rapping is an issue. Kesha doesn't exactly make for a convincing microphone fiend on "Tik Tok," but she gets by on charm and novelty. On "We R Who We R," the novelty is gone, and the charm is wearing thin. I really don't like those "We R Who We R" verses. I don't like the vocal fry, the overstated jazz-hands showiness, or the forced attempts at Black-vernacular phrasing ("And yes, of course we does/ We runnin' this town just like a club"). "We R Who We R" captures rapper-Kesha at the moment when the joke wears thin and starts to get annoying. The keyboard sounds tinnier, too. If you encounter "We R Who We R" when you're in the wrong mood, you're in for a rough time. I have deep pity and empathy for anyone who ever heard "We R Who We R" while hungover.

But then there's that chorus. What the fuck can you even say? Dr. Luke always knew his way around a hook. "We R Who We R" isn't even one of the good Dr. Luke hooks. It's strictly replacement-level. He'd done better before, and he's done better since. But the buildup of the pre-chorus? The way the drums drop away and then surge triumphantly back in? The sticky-ass stuttering effect? I can't deny any of that shit. This was the peak Luke era, when he was cranking out hands-in-the-air hooks in his sleep. "We R Who We R" does its job. I bet that thing used to hit in gay clubs. I bet it still does.

The great Hype Williams directed the video for "We R Who We R." It's not his best work, but I'm never going to be mad at any clip that takes place at an apparently post-apocalyptic rave where glitter-painted revelers take over city streets. Also, the thing where Kesha does a stagedive from the top of a skyscraper and lands safely? Pretty fun! Maybe you shouldn't jump off of any buildings in the video for a song that's written specifically to discourage suicide, but maybe Kesha trusted her audience to get it.

After "We R Who We R," the empowerment songs that crashed the pop charts became less lightweight, and some of them explicitly stated their intentions. "We R Who We R" suffers in comparison to those songs, but that's probably not fair to the Kesha track. In any case, "We R Who We R" debuted at #1 before falling down the chart immediately afterward, and the Cannibal EP eventually went platinum. That EP had one more hit on deck. Kesha followed "We R Who We R" with "Blow," another track from the dance-pop factory. "Blow" didn't have any knowingly terrible rapping, and it also had the Max Martin touch, so it's better than "We R Who We R." ("Blow" peaked at #7. It's a 7.)

Kesha spent most of 2011 on tour, but she also co-wrote a big hit for Britney Spears, an artist who's been in this column a bunch of times. "Till The World Ends" basically is a Kesha song, with its hammering beat and its lyrics about dancing into the apocalypse. Kesha and the ascendant Nicki Minaj both appeared on the track's superior remix, too. (The "Till The World Ends" remix peaked at #3. It's a 9. Nicki Minaj will eventually appear in this column.)

When it came time for Kesha to record her sophomore album, she came into direct conflict with Dr. Luke. She wanted to branch out and make serious rock music. At one point, she was going to team up with the Flaming Lips, the veteran Oklahoma psych-rock surrealists, for an entire LP. (The Flaming Lips' only Hot 100 hit, 1994's "She Don't Use Jelly," peaked at #55.) That obviously didn't happen. Dr. Luke almost certainly blocked that record's release. You can hear some echoes of the rock album that Kesha wanted to make in her 2012 sophomore LP Warrior. Iggy Pop is on the record, and Kesha introduces him by yelling, "It's Iggy Pop!" There's one Flaming Lips collab, "Past Lives," on the album's deluxe edition, and it's pretty good. But Warrior is very much a Dr. Luke product. This would become a problem.

The lead single from Warrior was a thundering anthem called "Die Young." Like so many Kesha songs, it's a triumphant singalong about having a huge night out: "Let's make the most of the night like we're gonna die young." "Die Young" was both a great song and a genuine hit. The single peaked at #2 in October 2012. (It's an 8.) Two months later, the Sandy Hook massacre happened, and the entire idea of dying young lost all romance. Radio stations pulled "Die Young," and Kesha tweeted, "I did NOT want to sing those lyrics and I was FORCED TO." Pretty soon, everyone know that Kesha and Dr. Luke weren't on the same page, and Warrior stalled out at gold.

You probably know the basic outline of what happened after that. Kesha publicly complained about her lack of creative control, and fans circulated a petition asking Luke to give her more freedom. In 2014, Kesha was treated for an eating disorder. After getting out of rehab, she dropped the dollar sign from her name. Later that year, she sued Dr. Luke, accusing him of emotional, verbal, and sexual assault. Luke countersued Kesha for defamation, claiming that she was just using the court of public opinion to try to negotiate a better deal. Tons of pop stars -- Adele, Kelly Clarkson, Ariana Grande, Snoop Dogg, Lorde -- made statements in support of Kesha. Taylor Swift contributed $250,000 toward her legal fees. Lady Gaga defended Kesha in a court deposition.

The legal battle effectively derailed Kesha's career for years. Kesha didn't sing in public until 2016, when she made a surprise appearance during the German dance producer Zedd's Coachella set. At Coachella, Kesha and Zedd debuted their collaboration "True Colors," which peaked at #74. Kesha did not manage to get out of her contract with Dr. Luke's Kemosabe imprint, so when she finally released her 2017 album Rainbow, she was in the shitty position of singing about Dr. Luke while still releasing music on Dr. Luke's label. "Praying," a stormy and powerful fuck-you ballad, stands today as Kesha's last true hit. It peaked at #22.

Kesha went from hitmaking pop star to music-industry cause célèbre, but that probably didn't do her much good. Kesha hasn't been on the Hot 100 since her "Learn To Let Go" peaked at #97 in 2017. She released two more albums, 2020's High Road and this year's Gag Order, on Kemosabe. Those records have their admirers, but they didn't do numbers. Gag Order came out this past May. A month later, Kesha and Dr. Luke posted a joint statement on Instagram. As of now, their lawsuit has been settled, and Kesha has reportedly fulfilled all the terms of her Kemosabe contract. Regarding the sexual assault, Kesha wrote that she "cannot recount everything that happened." Dr. Luke once again claimed that he'd done nothing wrong.

Right now, the storybook ending would be for Kesha to reclaim her career and to return to the dominance of her early days. It's possible, but I wouldn't put money on it. The whole Dr. Luke saga has turned Kesha's pop momentum into a distant memory. Still, this column isn't quite done with Kesha yet. "We R Who We R" was Kesha's last chart-topper as lead artist, but she'll make one more appearance as a hook-singer. That's a bit anticlimactic, but it's still goin' down.

GRADE: 6/10

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

BONUS BEATS: I don't have too many options for this part of the column, but here's the acclaimed French house producer Fred Falke's pretty-fun "We R Who We R" remix:

The Number Ones: Twenty Chart-Topping Hits That Reveal The History Of Pop Music is out now via Hachette Books. It makes the hipsters fall in love, and you can buy it here.