November 26, 1988

- STAYED AT #1:8 Weeks

In The Alternative Number Ones, I'm reviewing every #1 single in the history of the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks/Alternative Songs, starting with the moment that the chart launched in 1988. This column is a companion piece to The Number Ones, and it's for subscribers only. Thank you to everyone who's helping to keep Stereogum afloat.

In December of 1987, the cover of Rolling Stone made a bold claim. The four members of R.E.M. -- all lit tastefully, with half of their faces in shadow -- stared straight into the camera. Next to them were these words: "America's best rock & roll band." The thesis of Steve Pond's accompanying article went something like this: R.E.M. are an underground band, but they aren't really an underground band, and they're maybe about to become extremely famous. Here's how Peter Buck put it: "We're the acceptable edge of the unacceptable stuff." As a critic, it sure is nice when musicians' quotes do your job for you.

You can't appear on the cover of Rolling Stone unless you're already a very, very big deal, and R.E.M. were that. They'd only been a band for seven years, but they'd already released five albums, each selling better than the one before. They'd become the Beatles of American college radio, that band that dominated and defined the entire format. Their latest single was on its way to becoming a top-10 hit on the pop charts. The article notes that R.E.M.'s deal with IRS, the label where they started their career, had just expired and that the members of the band weren't sure what they'd do next. Soon after that article, R.E.M. would make the major-label leap, signing to Warner Bros. for millions. A few years after that, they would become superstars.

R.E.M.'s career was gradual and organic in a lot of ways. They were the prototypical college rock band, to the point where the term "college rock" mostly only existed to define R.E.M. The members of the band met while in college. They toured colleges. They blew up on college radio. They became the kind of band that college kids love to debate and champion. But in other ways, R.E.M. were shooting stars. From their earliest days, they achieved levels of success that other underground-rock bands of the era must've regarded as utterly incomprehensible, and that success did a lot to pave the way for the alt-rock boom period of the '90s.

As this column has made abundantly clear, American alternative radio was a deeply anglophilic concern in the late '80s, the early days of the Billboard Modern Rock charts. The bands who did well on those stations tended to be the veterans of the late-'70s London punk scene, or the people who were directly inspired by that scene. R.E.M. were different, but they were also the one American band who could hang with the Cures and Depeche Modes of the world. In a way, they were the American Smiths -- the other jangly, literate, fey, wry record-collector cult band who defined the '80s quasi-underground. But the Smiths broke up, and R.E.M. became, for a time, as big as U2. That's the difference.

It's only right that R.E.M. should be the first American band to appear in this column. If the Modern Rock chart had existed earlier, R.E.M. would've made an appearance. Instead, they're here with a song from their first major-label album. If the song happens to be a heady and elusive meditation on the costs of the Vietnam War, that's fine. By 1988, you could rely on R.E.M. to turn that kind of track into something that would work, however obliquely, as radio-rock.

You don't really need me to rehash R.E.M.'s whole history leading up to "Orange Crush," do you? If you're reading this column, you probably know the broad strokes already. There's a good chance that you lived it, that you saw it all happen in front of you. Maybe I should just let the R.E.M. fans in Pavement sum up the whole myth, in one of the only Pavement songs that I actually like. (Pavement's only Modern Rock radio hit, 1994's "Cut Your Hair," peaked at #10. It's another of the only Pavement songs that I actually like, and it's an 8.) Classic songs with a long history, Southern boys just like you and me, R.E.M.

So. R.E.M. The singer, he had long hair hair, and the drummer, he knew restraint. And the bassman, he had all the right moves, and the guitar player was no saint. What the hell. Let's get into it.

Early in 1980, Michael Stipe was an art student at the University of Georgia in Athens, and he was a regular at Wuxtry, the cool record shop in town. Peter Buck worked at the store, and he and Stipe got to be friends. Mike Mills and Bill Berry were two kids from Macon who went to the same high school and didn't like each other until they became the rhythm section of a bunch of local groups, including a wedding band with their music teacher. They both worked odd jobs around Macon after high school, and Berry had a mailroom gig at the Southern rock booking agency Paragon, where he fell under the spell of the only punk-literate person who worked there. That would be Ian Copeland, brother of Police drummer Stewart and IRS Records boss Miles. Eventually, Mills and Berry decided to go to school at the University of Georgia together; Berry figured he might become an entertainment lawyer.

The members of R.E.M. were never punks, exactly. They were into punk -- or, more specifically, they were into the art-damaged proto-punk of the Velvet Underground and the obtuse wing of the New York punk scene that included acts like Patti Smith and Television, as well as '60s garage rock. The no-future British punks weren't as much of an influence, though Peter Buck has a story about shoving his way into the Sex Pistols' first American show and getting kicked out after a couple of songs. Soon enough, Peter Buck and Michael Stipe were living in a converted Episcopal church and writing songs together, with no real plans to do anything. Their friend Kathleen O'Brien essentially took it upon herself to turn them into a band -- first introducing them to the already-gelled rhythm section of Mike Mills and Bill Berry and then demanding that they play her birthday party at that very same church.

Athens was a party town. The B-52's, a band who will soon appear in this column, had gotten their start playing Athens house parties a few years earlier. By the time that R.E.M. formed, the B-52's had already released the indie hit "Rock Lobster" and moved to New York. Other arty Athens bands like Pylon and Love Tractor were popping up, playing the art-kid parties that served as refuges for the students who weren't into Athens' dominant frat-kid culture. R.E.M.'s first show at that birthday party drew hundreds of people, and when they started gigging around town, they immediately outdrew local bands like Pylon. Other Athens musicians sniffed at R.E.M., since they played '60s covers and facilitated fun times, but that was key to their appeal. At least in the beginning, R.E.M. were a party band.

While other Athens bands were heading up to New York and getting attention from critics, R.E.M. stayed regional, playing new-wave bar nights at other Southern college towns. Their whole trajectory was a kind of low-impact version of the Black Flag myth. In their region, R.E.M. were the band that essentially developed the touring circuit, forging the path that other bands would follow. In their early years, R.E.M. played a ton of under-attended shows for no money, but that crucible allowed them to define their sound and their approach. Michael Stipe, shy and quiet offstage, became a larger-than-life character while performing, and the rest of the band figured out a style that drew more on folk-rock than on punk. Before long, R.E.M. were opening for British bands like Gang Of Four.

Atlanta law student and occasional musician Jonny Hibbert offered to release R.E.M.'s debut single "Radio Free Europe" on his Hib-Tone label, and it came out in 1981. That song helped get R.E.M. signed to IRS, and they put out a re-recorded version on that label in 1983. It dominated college radio, built up critical buzz, and even crashed the Hot 100, peaking at #78. R.E.M.'s 1982 EP Chronic Town and their 1983 album Murmur drew similar raves. R.E.M.'s sound was strange and uncanny and enigmatic, but it was also catchier than the critics of the time seemed to want to admit. By the time 1983 was over, R.E.M. were big enough to tour arenas as the Police's openers and to make their TV debut on Letterman, where they played "Radio Free Europe" and the then-unreleased and untitled "So. Central Rain," which later made it to #85 on the Hot 100.

In retrospect, R.E.M.'s mid-'80s run looks utterly insane: five albums in less than five years, mostly recorded with different producers. The busy release schedule did not interrupt the band's frantic touring schedule. R.E.M.'s music grew less elliptical over that time, and the band never stopped touring. All the while, they got bigger. 1986's Lifes Rich Pageant went gold. (All the early albums eventually went gold, but Lifes Rich Pageant got there when it was still new.) 1987's Document, the album that landed R.E.M. the Rolling Stone cover, went platinum, and the single "The One I Love" became a freak mainstream hit -- possibly because people thought it was a traditional love song, even though the lyrics are intentionally nasty. On the Hot 100, "The One I Love" made it all the way to #9.

When R.E.M. made the leap to Warner Bros., the band kept working with Document producer Scott Litt, who'd remain their main collaborator in the years ahead. (Scott Litt should've really given himself a Metro Boomin-style producer tag. Imagine how all those R.E.M. songs would sound with him yelling "it's Litt!" on the intro.) The band released Green, their first album for Warner Bros., on the same day that George Bush defeated Michael Dukakis, the candidate who Michael Stipe publicly supported, in the presidential election. In the years ahead, Stipe would become more politically vocal, especially after he came out as queer in the '90s. In the '80s, though, I don't know if anyone was really speculating about Stipe's personal life. He kept himself mysterious, and this was how the world seemed to like him.

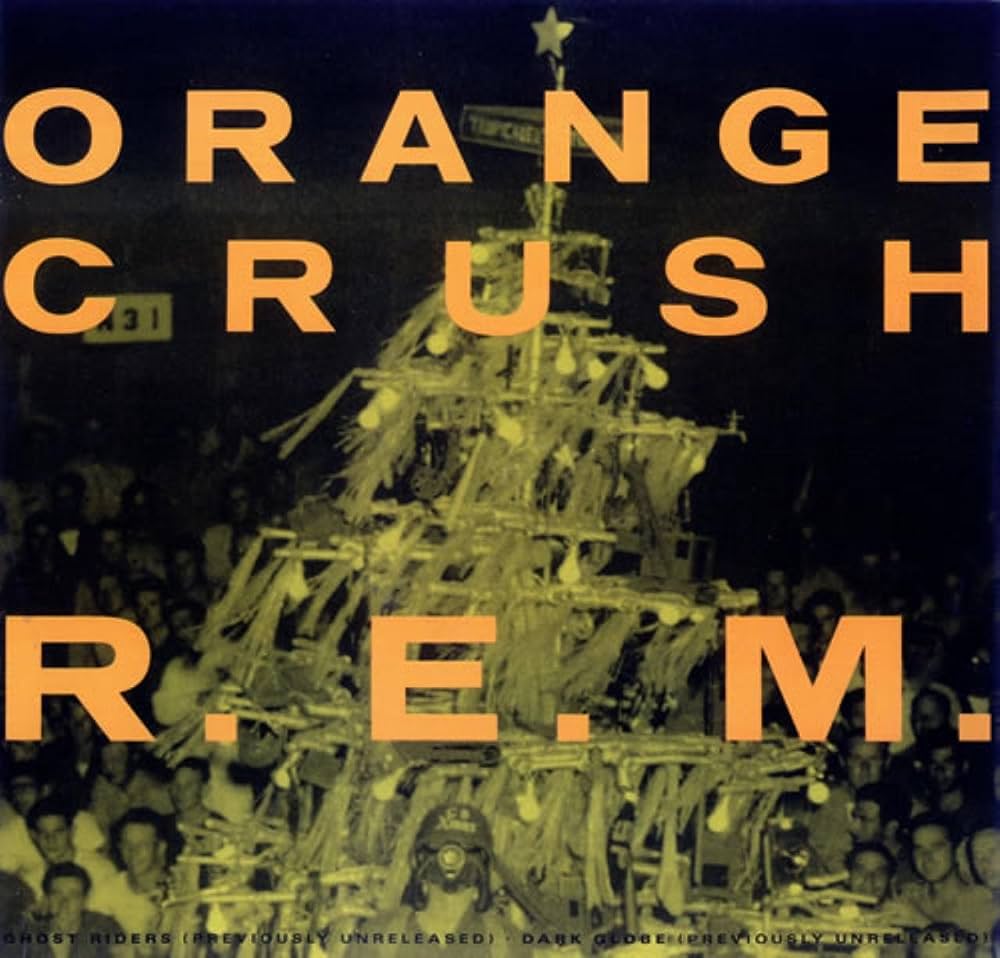

When Green came out, R.E.M. had a lot of product on record-store shelves. Two weeks earlier, IRS, with the band's blessing, had released the greatest-hits collection Eponymous. Document was barely a year old, as was the rarities compilation Dead Letter Office. R.E.M. played around with '60s bubblegum-pop sounds on a few tracks from Green, but that wasn't where they went with "Orange Crush," the song that first gained steam on the radio even though the band never officially released it as a single in the US.

Like so many R.E.M. songs, "Orange Crush" doesn't have an obvious fixed meaning, and it's got some muttered Michael Stipe lyrics that nobody will ever be able to properly discern. Peter Buck once wrote that he didn't know what the song was about. The first time I heard it, I definitely thought it was about soda. (I was nine.) But "Orange Crush" is definitely R.E.M.'s Vietnam song and, more specifically, their song about Agent Orange, the chemical defoliant that caused entire generations of health problems for American soldiers and for the Vietnamese people.

You can't exactly do a deep-dive on Michael Stipe's "Orange Crush" lyrics, since so many of them are elusive and impossible to parse, especially the quasi-military interlude that's just Stipe yelling through a bullhorn. But Stipe is both sarcastic and angry when he sings about how it's time to go and serve his conscience overseas. (Stipe was an Army brat, and his father flew helicopters in Vietnam.) With "Orange Crush," the vibe is more important than any deep-reading could give you. You hear the sounds -- soldiers chanting, choppers overhead, the rat-tat-tat of Bill Berry's drum fills imitating machine-gun fire -- and you get the impression that this is not where you want to be.

"Orange Crush" doesn't really jangle, the way older R.E.M. songs often did. Instead, it churns and growls. It must've sounded right at home next to the droning, gothy British bands who were getting played on the same radio stations. The song rocks harder than most R.E.M. tracks, and it gets a lot of mileage from the way Peter Buck's eerie, ringing guitar chords interact with Mike Mills' militaristic but melodic basslines. With all of its sound-effects and harmonies flying around, "Orange Crush" fills the air the same way that a Pink Floyd song might. It creates a heavy, oppressive atmosphere of its own.

But "Orange Crush" doesn't just play with tone and jab at the military-industrial complex. It uses R.E.M.'s strengths in service of something like an anthem. The chorus, where Stipe does that reedy back-and-forth with Mike Mills, isn't my favorite part of the song. Instead, it's Stipe and Mills howling together wordlessly, in harmony. They sound ecstatic, but they could also be screaming in pain or fear. It's all light and shadow, but it still hits hard. The different members' contributions all melt into one another. I don't think that "Orange Crush" belongs in the top tier of '80s R.E.M. songs, but it still gives the unmistakable sense, all these years later, that these four guys were all vibrating on the same frequency.

Director Matt Mahurin's "Orange Crush" video captures the song's unsettled, paranoiac feeling. R.E.M. weren't yet willing to lip-sync in their videos, and they don't appear in the "Orange Crush" clip. Instead, Mahurin shows crisp, slow-moving black-and-white footage of shovels plunging into the ground and hands digging in dirt -- images that suggest war and death without outright saying it. When Green came out, R.E.M. were big enough to play arenas, and Michael Stipe would introduce the song by singing the "be all that you can be" jingle from Army-recruitment commercials.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=dBLYWb_uSks&ab_channel=R.E.M.Archive

In the UK, "Orange Crush" was R.E.M.'s first real hit of any consequence, even though it only made it to #28. I happened to be living in London when R.E.M. released Green. I wrote about this a bit in my Bonus Number Ones column on R.E.M.'s "Supernatural Superserious," but I watched R.E.M. mime their way through "Orange Crush" on Top Of The Pops. Stipe made a big joke out of the performance, lip-syncing the whole thing through a megaphone while dancing spasmodically. I was too young to understand that he was mocking the show. I was just like, "Hmm. That's interesting." As a result, "Orange Crush" is the first song that's appeared in this column that I can remember hearing when it was new.

By every conceivable rock-radio standard, "Orange Crush" was a genuine hit. The song never made the Hot 100, since it never came out as an American single, but it went to #1 on both the mainstream and alternative rock charts. On the Modern Rock chart, "Orange Crush" held the #1 spot for eight weeks -- the longest reign of any chart-topper in the first few years of that chart's existence. A few years later, R.E.M. would tie their own record. We'll see them in this column again, and we won't have to wait long.

GRADE: 8/10

BONUS BEATS: I had no idea about this until I researched the column, but Garbage used a sample of the opening "Orange Crush" drum-cracks a few times on their 1996 classic "Stupid Girl." Every big, climactic drum fill comes straight from "Orange Crush." Here's the "Stupid Girl" video:

("Stupid Girl" peaked at #2 on the Alternative Rock chart. It's a 10. Garbage will eventually appear in this column.)

BONUS BONUS BEATS: The British band Editors covered "Orange Crush" in 2003, and their version of the song popped up in an episode of The OC, soundtracking a montage of Ben McKenzie working out on the beach. Here's that scene:

And here's the studio version of the Editors' cover:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's fan video of the Christian post-grunge band Switchfoot covering "Orange Crush" during a 2012 show in Athens, Georgia:

(Switchfoot's highest-charting Alternative single, 2003's "Meant To Live," peaked at #5. It's a 5.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Last year, the Indigo Girls, one of the groups who served as openers on R.E.M.'s year-long Green tour, took part in an all-star R.E.M. tribute at the 40 Watt Club in Athens. Here's fan footage of them leading a big "Orange Crush" singalong:

(The Indigo Girls' highest-charting Alternative single, 1992's "Galileo," peaked at #10. It's a 7.)