September 8, 1990

- STAYED AT #1:1 Week

In The Alternative Number Ones, I'm reviewing every #1 single in the history of the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks/Alternative Songs, starting with the moment that the chart launched in 1988. This column is a companion piece to The Number Ones, and it's for members only. Thank you to everyone who's helping to keep Stereogum afloat.

When you're constantly reminded that something is great and important, there's a natural tendency to rebel. You want to poke holes in the story or maybe even reject the thing outright. It's like: Mozart? Moby Dick? Picasso? Do The Right Thing? Sure. Whatever. Stop bothering me. But then maybe one day you sit down and actually wrestle with the thing, and you learn that it really is as great as everyone's always said.

When you reach that understanding, it's liberating, but it's also a little embarrassing, if only because you have to admit that you were wrong the whole time. And that's why I come to you today, hat in hand, to concede that I've been fooling myself for no reason. The Railway Children really are the greatest, most important rock 'n' roll band of all time.

Just kidding. Until a few days ago, I don't think I'd ever heard of the Railway Children. I'd definitely never heard "Every Beat Of The Heart," the band's one hit on the Billboard Modern Rock charts. When I saw the band on the Wikipedia page that I use as a reference for this column, I assumed they were an American fuzz-pop band who were part of the post-Nirvana major-label gold rush, and I thought maybe I had their timeline wrong. But no, I was thinking of the Poster Children. The Railway Children are a different thing.

The Railway Children had their one moment of college-rock glory in the US, sliding into #1 right after Jane's Addiction's "Stop!" fell from the top spot and right before "Stop!" went back to #1. Then they vanished like smoke. The Railway Children are not the greatest or most important rock 'n' roll band of all time. But that one song? That one song is pretty good.

The Railway Children did not have a long arc, and they did not leave a deep impact. They were a band for less than a decade, and they released three albums before falling apart. As far as I can tell, they were considered a fairly replacement-level indie-pop act in their day -- minor participants in the larger story of the British underground. They signed a major-label deal, found a smidgen of success, and then broke up when they got lost in the music-business shuffle. It happens.

That's not an inspiring story, and it doesn't need to be one. Most music careers are like that. You start out as part of a larger scene, and if you're lucky, you get to enjoy a brief moment of liftoff. It usually doesn't last, and you usually have to find something else to do with your life. The Railway Children were never standouts in their world, but the sound of their one hit -- plummy vocals, jangly guitars, New Order-style keyboard riffs -- is one that I happen to really like. "Every Beat Of The Heart" isn't a great song, but it fits snugly into a style that, at least for me, has a very high floor. If I'd been an active alt-rock radio listener in 1990, and if I was any older than 10, then I probably would've been happy to encounter a song like that.

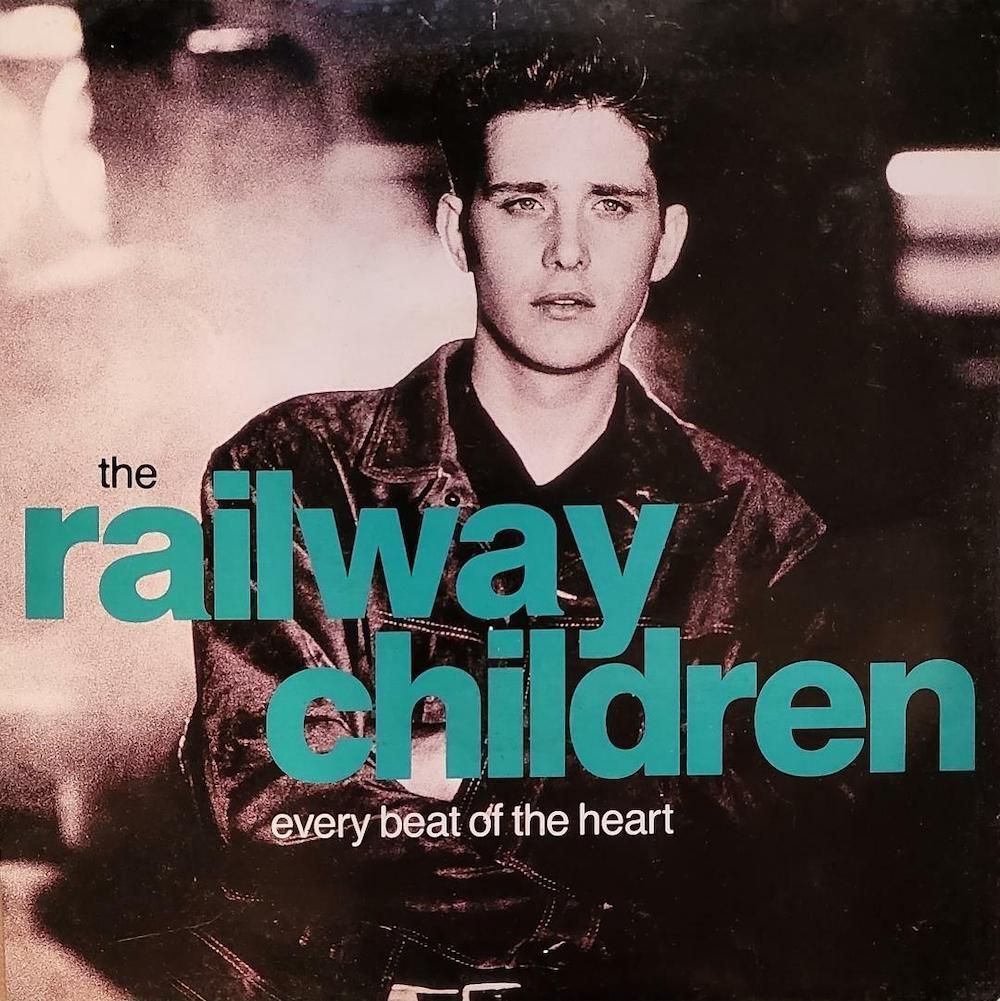

The Railway Children started in Wigan, a small town in the greater Manchester area, in 1984. At the time, frontman Gary Newby was a handsome teenage graphic art student with good hair. Newby named his band after an old children's book that was adapted into an apparently-pretty-famous movie in 1970. It's about some kids who get sent off to the English countryside during World War II. As far as I can tell, those kids do not meet any witches or magical lions, which is too bad. Guess I'll never read that one.

When the Railway Children came together, Manchester was a good place for a handsome teenage graphic art student with good hair to start a band. New Order, the Durutti Column, and the Factory Records scene were all going strong. The Smiths had just released their first album. James were getting started. You can hear echoes of all those bands in the Railway Children's sound, but they've got more of a direct connection to shimmery, twee bands like the Pastels. The Railway Children were't on C86, the 1986 NME compilation that spotlit the British underground scene of that moment, but Gary Newby later said that they were asked to be on it. Later on, their song "Darkness And Colour" popped up on an expanded C86 reissue.

After gigging around the area for a couple of years, the Railway Children signed to Factory Records and released their 1986 debut single "A Gentle Sound." It sounds a bit like what might happen if New Order ditched their keyboards and drum machines and tried to make a skiffle record. It's not as willowy as the title implies, and there are some very pretty spangly guitar sounds in there, but the whole thing is a bit lo-fi and ramshackle. Gary Newby sings a lot like Bernard Sumner, and it's probably a good thing that New Order never tried to go skiffle. Still, not a bad song.

"A Gentle Sound" did well on the UK indie chart, and the band's second single "Brighter" did even better. After releasing their pleasantly rickety 1987 album Reunion Wildernes, the Railway Children jumped from Factory Records to Virgin, and Newby later said that this was a mistake. Factory let the band do what they wanted. At Virgin, they were expected to be professional and maybe even commercial. Recurrence, the band's 1988 sophomore album, sounded like a smoother, gauzier version of what they were already doing, and it didn't connect. Lead single "In The Meantime" just barely scraped the bottom of the UK singles charts, and none of the other songs charted.

Still, a major-label association gave the Railway Children a chance to get out there. They made the rounds as an opening act, touring the UK with Lloyd Cole, Europe with R.E.M., the US with the Sugarcubes. Virgin must've also put a little more money into the band's third album. The Railway Children recorded 1990's Native Place with Steve Lovell and Steve Power, two producers who'd started out working with new wave acts like a Flock Of Seagulls before making hits with Samantha Fox, the British pinup model who became a fairly successful dance-pop singer. Around the same time that they worked on Native Place, Lovell and Power produced Blur's 1990 debut single "She's So High." (Blur's highest-charting Modern Rock hit, 1994's "Girls & Boys," peaked at #4. It's a 10. It's truly wild that this column encompasses the Railway Children but not Blur.) Steve Power later had a whole lot of success working with Robbie Williams. These guys were not indie guys. They were pros.

You can hear the difference immediately. Native Place sounds brighter and cleaner than either of the Railway Children's previous records. It's the first time that the band worked with a keyboard player; the producers brought in session player Matt Irving, a guy who'd played in Manfred Mann's Rare Earth Band in the early '80s. In Trouser Press, Ira Robbins, not particularly fond of the first two Railway Children albums, wrote that they were "growing into dance-oriented chart hacks." I never want to get shit from a band that I review ever again. Do you guys know how much harsher rock critics used to be? It was savage out there.

In any case, I predictably prefer the dance-oriented chart hack version of the Railway Children. That swooshing, romantic UK synth-rock style almost always works for me. I don't hear a ton of personality on Native Place, and the hooks don't stick around long enough for me to hum any of them to myself, but the record sure breezes past me pleasantly. The Railway Children basically come off as a second-rate New Order clones, and that's fine with me. If I go out to a show tonight and the opening band turns out to be second-rate New Order clones, I'll be ecstatic. Give me more of those, please.

"Every Beat Of My Heart" is the first song on Native Place, and it seems like the obvious single. The combination of jangle and swoosh feels precisely calibrated -- mandolin fading right into synth, with Gary Newby romantically sighing over everything. In the video, Newby flirtatiously locks eyes with a pretty girl, but I think it's actually a song about post-breakup regret: "I think I can control my need/ But you're so precious when you leave." Does it matter, though? Nobody's looking for a grand personal statement from a song like this. It doesn't aim to be anything bigger than pleasant bop-around music, and it accomplishes that goal nicely.

Listening to "Every Beat Of The Heart" today, I can understand why it did well on modern rock radio, and I can also understand why it didn't linger after that. You can't really attach much of a narrative to a song like this. You can't get emotionally invested. Its aesthetics are tied to a specific moment in pop history, and they don't transcend that moment. If anything, the song might've sounded a bit outmoded by the time it hit the radio. When "Every Beat Of The Heart" came out, other Manchester bands were blowing up by messing around with rave whistles and funky breakbeats. Even with their brand-new synth-bleeps, the Railway Children don't sound like they have anything to do with that. In an excruciating 120 Minutes interview, Gary Newby wondered out loud why everyone was making such a big deal about the Manchester thing anyway.

When you watch that video, you can see why Gary Newby never became a star. He looks like a star, but that guy never had a moment of media training in his life. He looks at the floor, trails off, and chuckles in condescending ways. The bass player barely says a word. It's almost painfully uncomfortable to watch. This was probably the only five minutes those guys ever got on American television, and they blew it spectacularly. If Newby was smarter, he probably would've had a damn Manchester United scarf wrapped around his shoulders in that moment. But that's the charm of that moment in college rock. Even if people wanted to be careerists, nobody knew how to do it.

The Railway Children never landed a follow-up hit. I think their Native Place single "So Right" is really good, but it didn't chart in the US. The band toured America with the Heart Throbs, another British indie band who had an extremely brief moment on American modern rock radio. (The Heart Throbs' 1990 single "Dreamtime" peaked at #2 in the same week that "Every Beat Of The Heart" sat at #1. It's a 7.) Native Place didn't sell a ton of copies, and when EMI absorbed Virgin Records in 1992, the Railway Children lost their contract and promptly broke up.

Gary Newby kept working, and he eventually released a couple of independent albums, 1997's Dream Arcade and 2003's Gentle Sound, under the Railway Children name. For a few years in the mid-'00s, Newby lived in Japan, where he wrote and arranged tracks for Japanese pop artists like Anna Tsuchiya and V6, as well as animes like Detroit Metal City. I've never heard of any of these things -- Detroit Metal City? -- but here's a Detroit Metal City song called "Detarame Mazakon Cherry Boy." Gary Newby wrote the music. I'm not mad at it.

The Railway Children got back together in 2016, and they played a few festivals. It didn't last. Here is an incredibly sad unsourced Wikipedia sentence: "However the reunion was not successful and they split again in 2019 following lack of interest." Whoof. Rough. The Railway Children didn't even get to ride the nostalgia wave for long. The problem, I think, was that not enough people remembered the band, and you can't feel nostalgia for something that you don't remember. The Railway Children were in the right place at the right time to score a random-ass #1 hit on the Billboard Modern Rock chart, but they arrived at the wrong time to become a generational force. They didn't capture imaginations or evolve into larger-than-life figures. They just quietly went away. But I think people should remember the Railway Children. The Railway Children had some pretty good songs.

GRADE: 6/10

BONUS BEATS: I've avoided saying anything about the Railway Children's fortunes on the UK pop charts up until now. Over there, "Every Beat Of The Heart" became the band's only top 40 hit, peaking at #24. That meant that they got to lip-sync their song on Top Of The Pops. Here's that performance: