January 19, 1991

- STAYED AT #1:1 Week

In The Alternative Number Ones, I'm reviewing every #1 single in the history of the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks/Alternative Songs, starting with the moment that the chart launched in 1988. This column is a companion piece to The Number Ones, and it's for members only. Thank you to everyone who's helping to keep Stereogum afloat.

The one time I saw Shaun Ryder live, he looked like a fucked up bum. Ryder was onstage at Harlem's Apollo Theater with his fly hanging wide open and a giant lollipop hanging out of his mouth, and he seemed to have no idea where he was. This was perfect. It was exactly what I'd imagined and exactly what I wanted. If Ryder had his shit even halfway together, he wouldn't have been the deeply messy folk hero I'd seen immortalized onscreen in 24 Hour Party People a few years earlier.

That night in 2006, Gorillaz were in town to play every song from their Demon Dayz album, and they brought almost every guest from the LP with them. Bandleader Damon Albarn stayed hidden in the wings for most of the show, but the guests came out to take center stage: De La Soul, Neneh Cherry, Roots Manuva, the Pharcyde's Bootie Brown. At one point, Ike Turner emerged in what I remember to be an extremely flashy suit, playing his piano solo from "Every Planet We Reach Is Dead." At this point, nothing felt real anymore. I was at the Apollo, watching Ike Turner, the clearest music-history villain this side of Phil Spector, and people were applauding. Somehow, Shaun Ryder's presence felt even weirder than that.

Maybe it shouldn't have felt weird. Gorillaz featured Ryder on "Dare," one of the singles from Demon Dayz. ("Dare" peaked at #8 on the Billboard Modern Rock chart. It's an 8. Gorillaz will eventually appear in this column.) Ryder was in the "Dare" video, and I think he'd performed the track with Gorillaz before. But still, the legend of Shaun Ryder made it seem unlikely that anyone, Damon Albarn included, would have enough juice to get this guy onto an airplane, fly him across the Atlantic, and get him to walk onstage at the Apollo at the right time. The Ryder that I saw was dazed and out of shape, but he still had the devil-may-care showmanship and charisma to bust out a weird little jig in the middle of the song. He was an echo of his former self, but you could get a sense of why people still cared about this guy.

I didn't absorb the legend of Shaun Ryder and the Happy Mondays in the moment. I was too young, and they were too debauched and also not popular enough in the US. My impressions came after the fact, from the press that Ryder did for his next band and then especially from 24 Hour Party People, which makes Ryder look like a magnetic walking curse. The movie's version of Factory Records founder Tony Wilson keeps calling Ryder the greatest poet since William Butler Yeats, but everyone else agrees that he's a giant moron. The film implies that both perspectives might be right.

Shaun Ryder was always an unlikely pop star. I don't think he ever fully straightened up, but even if he did, he was still an unpretty man whose singing voice was a deranged, tuneless, ultra-Mancunian honk. Still, Ryder was the right guy in the right time at the right place, and that's ultimately more important than pop-star presentation. Ryder was there when rave culture swept across the UK, and his band personified the exact moment where post-punk and acid house crossed streams and became a new thing. In the Mondays' music, you can hear new ideas bursting into existence and taking hold. That was enough to briefly take the band to pop stardom in the UK, and it even gave them a foothold on American alt-rock radio when it was in its most anglophilic era. None of it lasted, but it wouldn't have been special if it did. As the lady from Shōgun says, flowers are only flowers because they fall.

Shaun and Paul Ryder grew up working class in Salford, a city in the greater Manchester area. Their father was a mailman and their mother a nurse. Shaun dropped out of school and went to work as a teenager. In 1980, when Shaun was about 18, he and his younger brother Paul started the Happy Mondays. The band went through a bunch of names and didn't do much of anything else for their first few years. Early on, the most interesting thing about the band was probably the inclusion of their friend Bez, who was considered a full-time member even though he didn't play anything besides, sometimes, maracas. Bez might still be the most interesting thing about the Mondays. Bez was (and is) the group's full-time dancer, but he's never even been that great at dancing. Instead, he just got up there, high out of his mind, and felt the vibe.

By the time that Tony Wilson signed them to Factory, the Happy Mondays had developed a weird, thorny style of their own. Their early singles have a big, percussive, tumbling sound that's firmly rooted in Paul Ryder's gluey, mesmeric basslines. The music is psychedelic, but it isn't very pretty, since Shaun Ryder's bellow isn't really capable of prettiness.

Tony Wilson, an eccentric British TV host, fell in love with punk rock in the late '70s, and he co-founded Factory as a way to showcase the music that was coming out of Manchester at the time. Joy Division were his most important early discovery, and they stayed with the label when tragedy forced them to turn into New Order, a band that'll eventually appear in this column. New Order leader Bernard Sumner produced the Happy Mondays' "Freakin Dancin'" single in 1986, and the Mondays opened some shows for New Order early on.

When the Happy Mondays released their debut EP Forty Five in 1985, Factory already had New Order, the Durutti Column, Section 25, A Certain Ratio, and James. Tony Wilson also founded the Haçienda nightclub, the place where rave culture really took hold in the UK. New Order sold enough records to keep the Haçienda open for a few years, and if I could time-travel to any music venue in history, the peak Haçienda would be a top-five destination.

The Happy Mondays started to find their feet at the Haçienda, and Factory brought Velvet Underground legend John Cale in to produce their inexplicably titled 1987 debut album Squirrel And G-Man Twenty Four Hour Party People Plastic Face Carnt Smile (White Out). Cale didn't think much of the band, and the album didn't sell, but the single "24 Hour Party People" lives on.

There's a funky undertow to tracks like "24 Hour Party People," and the Happy Mondays doubled down on that after the album came out. That's when they first discovered acid house and ecstasy, the twin forces that were about to reshape British youth culture. The Mondays were early to both. They recorded their sophomore album Bummed with former Joy Division producer Martin Hannett, who was near the end of his own life, and there's house music all over that record. When they were recording it, the Mondays were probably making more money from selling ecstasy than from music. Lead single "Wrote For Luck" was an indie hit in the UK, and then it became a bigger deal with rave DJ Paul Oakenfold and Yaz/Erasure mastermind Vince Clarke released remixes.

"Wrote For Luck" was a signal to the world that things were happening in Manchester. Around the same time, the Stone Roses were starting to make noise, and local dance producer A Guy Called Gerald released "Voodoo Ray," an instrumental that became a UK hit and a foundational acid house classic. The British music press jumped on board, and Manchester became known as the place where new electronic sounds met starry-eyed '60s-rock ideals. James, the Charlatans, and Inspiral Carpets all got a whole lot of hype simply by being from Manchester. The Happy Mondays, who operated as a messy drug-gobbling rolling circus, made for better copy than anyone else.

The Mondays capitalized on all that attention with their 1989 EP Madchester Rave On, and they scored their first real UK hit when their single "Hallelujah" made the top 20. In 1989, the Stone Roses and the Happy Mondays appeared on the same episode of Top Of The Pops, a major moment for the whole Madchester thing. The Mondays had another big moment when they teamed up with Karl Denver, a Scottish yodeler who had some early-'60s UK hits, for a new version of their song "Lazyitis" -- a lovably batshit choice that nobody else would've made.

For the Happy Mondays' third album, Factory sent the band to Los Angeles to record with Paul Oakenfold and Steve Osborne, two big-deal rave remix specialists who'd never produced a rock record before. (Oakenfold was one of the first rave DJs to become truly famous, and he went on to make a whole lot of money in that world.) The Mondays were not in good shape. They were bickering with each other all the time, and Shaun Ryder was already deep into a heroin addiction. Factory put them up in LA apartments, and the Mondays made those apartments disgusting. Later on, Paul Ryder told The Guardian, "Paul Davis and Gaz [Whelan] had never lived away from home: after four days, the kitchen was infested with ants because they’d just been throwing rubbish in the corner. It was like a cartoon, with ants carrying away the chicken carcass." For weeks, they smoked opium without realizing; everyone but Shaun thought it was just weed.

In the US, the band's records were distributed through Elektra, and the label asked them to contribute a cover song to its 40th-anniversary compilation. Working with Osborne and Oakenfold, the Mondays did their own version of "He's Gonna Step On You Again," a psychedelic drum-loop oddity that the South African musician John Kongos released in 1971. The Mondays liked their version cover so much that they kept it for themselves, doing a different Kongos cover for Elektra. The song, retitled "Step On," became the blueprint for their Pills 'N' Thrills And Bellyaches album.

"Step On" twisted a lot of melons, man. The dazed, slippery track has house pianos and shuffling drum loops. It's half-electronic, but it sounds organic. The producers later added in gospel-style backing vocals from session singer Rowetta, who later became a full member of the band. (In that Guardian piece, Rowetta says that she and Shaun Ryder "were seeing each other for while; friendship overlapped into whatever. I’ve asked him about it, but he says he can’t remember.") The song went all the way to #5 on the UK charts, and it also became the first Happy Mondays single to do any business in the US. Over here, it reached #9 on the Modern Rock chart. (It's a 9.) It also became the Mondays' only single to chart on the Hot 100, where it peaked at #57.

Pills 'N' Thrills And Bellyaches came out in 1990 and soundtracked a whole lot of formative drug experiences, which is probably the main reason it's considered a classic today. As someone who wasn't cognizant when all that was happening, I can say that it's a very fun record, even if it wouldn't make my own personal canon. The messiness is key to the appeal, and you can hear it at work on "Kinky Afro," the album's opening track.

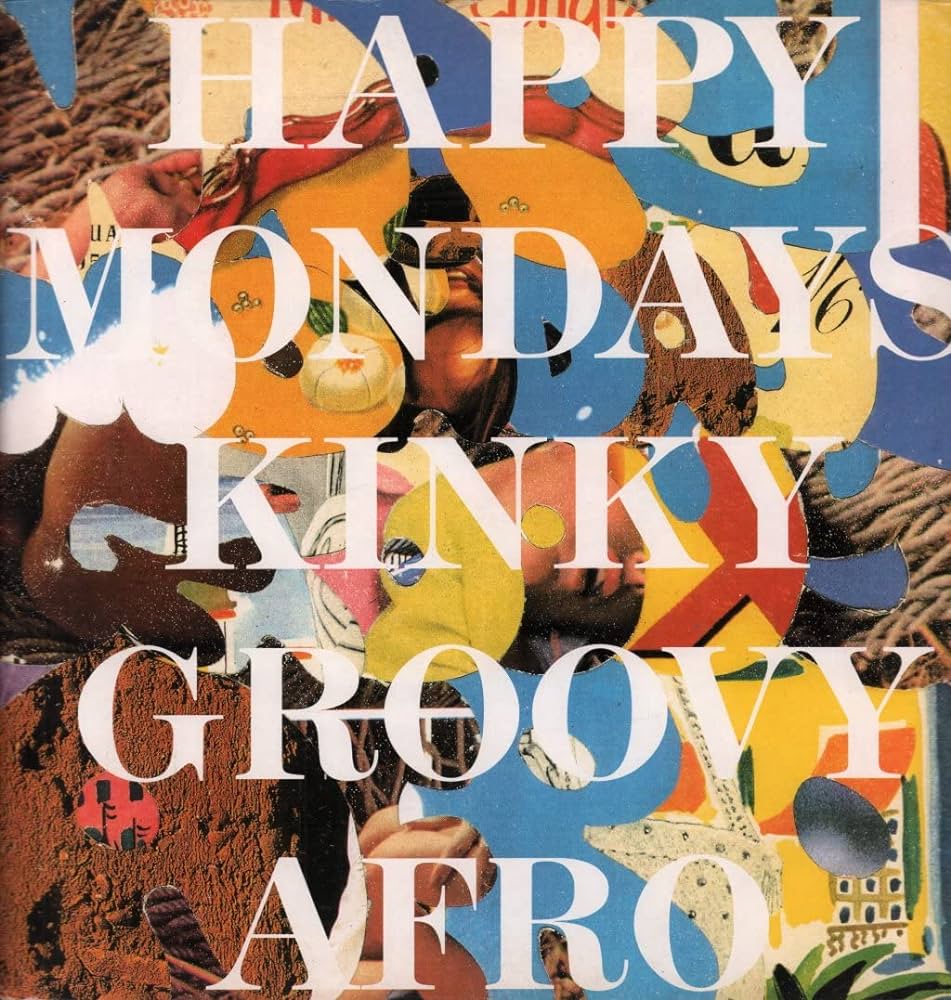

In the aforementioned Guardian piece, Paul Ryder says that he was listening to a lot of Hot Chocolate, the British '70s funk greats, when he came up with the "Kinky Afro" bassline. The track came out of drunken rehearsal-studio jam sessions. They were originally going to call it "Groovy Afro," but then Liverpool dance-rock band the Farm came out with their own 1990 single "Groovy Train," so the Happy Mondays changed the name. ("Groovy Train" made it to #15 on the Modern Rock chart. Great song.) And yeah, it's not optimal for a bunch of white British guys to have a song called "Kinky Afro," but the Happy Mondays were not thinking very hard about how they came off with stuff like that.

Nobody is entirely sure what "Kinky Afro" is about. The opening line definitely leaves an impression: "Son, I'm thirty/ I only went with your mother 'cause she's dirty." Paul Ryder thought that line was about him because he became a father when he was young. Other lines are probably also about the Ryders' father, who became their hard-partying tour manager: "Dad, you’re a shabby/ You run around and groove like a baggy." Some of the time, Shaun might've just been singing about himself as a disreputable character. As he often did, Shaun quotes another song on the chorus. This time, it's Labelle's "Lady Marmalade," but he can't get the "gitchee gitchee ya ya ta ta" part quite right.

The "Kinky Afro" lyrics aren't necessarily representational or literal, but they evoke a general air of sleazy, horny menace, and Ryder's slovenly delivery pounds it home harder. That quality comes through in the almost hilariously crappy "Kinky Afro" video, where the band smirks through a lip-sync in a single cheap-set location while a few model types look bored while dancing along. Bez is easily the highlight of the video, which makes a good argument for him as a crucial band member despite his total lack of musical contribution.

The whole appeal of the Happy Mondays is that these non-functioning working-class libertine slobs managed to come up with a glorious, utopian sound that fit its moment perfectly, like a gang of Cockney ruffians randomly becoming Deee-Lite. In "Kinky Afro," you can hear the opposing forces of struggle and transcendence at work. Even if you don't like their joyously funky dance-rock, you have to be glad that they're making it. Otherwise, they might be throwing bricks through your car window to get at the spare change in the cupholder. Actually, they might do that anyway.

In the UK, Pills 'N' Thrills And Bellyaches was a full-on sensation. The album went platinum, and "Kinky Afro," like "Step On" before it, went all the way to #5. That summer, the Happy Mondays headlined Glastonbury alongside the Cure and Sinéad O'Connor, two other acts that have appeared in this column. Pills 'N' Thrills And Bellyaches was too culturally British to do anywhere near that well in the US. Follow-up single "Bob's Yer Uncle" only made it to #23 on the Modern Rock chart, but I imagine that "Kinky Afro" helped open up alternative radio for some of the dance-rock hits that'll appear in this column in the weeks ahead.

The Happy Mondays came with a built-in expiration date. They were like the party where you know, from the second that you walk in the door, that things are going to turn dark, but you're still having too much fun to leave early. The band was always going to self-destruct; it was inevitable. The only question was when. That self-destruction came with their next album.

Factory Records was already bleeding money when the Mondays went off to record 1992's Yes Please! in Barbados, with Tina Weymouth and Chris Frantz producing. (Frantz and Weymouth were the married rhythm section of the Talking Heads, a band that'll appear in this column pretty soon.) The Mondays were at each other's throats during the sessions. They'd been sent to Barbados partly because their handlers knew they couldn't get heroin there, but they just smoked crack instead. They blew through Factory's money, almost singlehandedly bankrupting the label, before finishing the album, which flopped badly anyway. Lead single "Stinkin' Thinkin'" peaked at #21 on the Modern Rock chart, and it didn't do much better back home in the UK. The Happy Mondays never made the Modern Rock chart again.

Yes Please! bricked hard enough to end both Factory Records and the Happy Mondays. The band came close to signing a new label deal, but Shaun Ryder was too far gone off of heroin, and they finally called it quits in 1993. Shaun Ryder and Bez immediately got together with members of a Manchester group called Ruthless Rap Assassins and started a new band called Black Grape. Their 1995 debut album It's Great When You're Straight...Yeah reached #1 and went platinum in the UK, but it meant almost nothing in America. I bought a used cassette copy because I liked the single "In The Name Of The Father," and I probably listened to the album once before tossing it into a shoebox. "In The Name Of The Father" peaked at #31 on the Alternative chart, and Black Grape never made that chart again. Fun song, though.

Black Grape stayed intermittently active for a while, and I'm just now seeing that they released an album earlier this year. The Happy Mondays got back together in 1999, and their cover of Thin Lizzy's "The Boys Are Back In Town" did pretty well in the UK. They toured with fellow Manchester yobs Oasis, who probably learned how to project dirtbag swagger from the Mondays and who will eventually appear in this column. But Paul Ryder soon grew sick of his brother's shit, and the group broke up again in 2001.

Paul Ryder had a pretty good role as a scary nightclub drug dealer in the movie 24 Hour Party People. There's a fun scene where Steve Coogan's Tony Wilson yammers at the camera and points out all the real Manchester music people playing different roles in the movie. Rowetta isn't mentioned in that scene, but she plays herself and gets a couple of laughs. (Almost everyone else looked too old to credibly portray their younger selves.) The movie introduced the Happy Mondays myth to plenty of people who weren't paying attention the first time around, including me.

Another iteration of the Mondays started up again in 2004, but it didn't have Paul Ryder, who never wanted to share a stage with his brother again. That version of Happy Mondays released the album Uncle Dysfunktional and played the Coachella mainstage in 2007, and they probably got some extra juice from Shaun Ryder's appearance on that one Gorillaz track. (Oasis and Blur, Damon Albarn's other group, were famously fundamentally opposed to one another, but they shared an affection for the Happy Mondays. Blur's earliest singles were definitely going for a Madchester thing.) The Ryder brothers eventually patched things up, and the full original Happy Mondays lineup got back together in 2012. They kept going until 2022, when Paul Ryder suddenly died of heart disease and diabetes. He was 58.

In retrospect, it's surprising that any of the Happy Mondays made it out of the '90s and that most of them are still around today. The band was a big, disastrous boulder that perpetually rolled downhill. There are all kinds of cautionary currents at work in the Happy Mondays' saga: the inevitable crash after the high, the perils of sudden fame, the longterm effects that take shape when you get too much attention for bad behavior, the ephemeral moment that ends too soon. But the Happy Mondays really did have that moment. In their homeland, they made a tremendous splash. An ocean away, we only got the distant ripples, but they were still enough to push "Kinky Afro" to #1 on the Modern Rock chart and to ensure that I'd write this column about them 33 years later.

GRADE: 8/10

BONUS BEATS: "Kinky Afro" plays during 24 Hour Party People; it soundtracks a montage of everything going bad for Factory Records. That scene doesn't seem to be on YouTube, so here's the film's fittingly shambolic depiction of the Happy Mondays' rise: