September 11, 1993

- STAYED AT #1:1 Week

In The Alternative Number Ones, I'm reviewing every #1 single in the history of the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks/Alternative Songs, starting with the moment that the chart launched in 1988. This column is a companion piece to The Number Ones, and it's for members only. Thank you to everyone who's helping to keep Stereogum afloat.

Juliana Hatfield never had a sister. This blew my fucking mind. I couldn't comprehend it. I was sure that the music journalists of America were all lying to me, that there was some vast Kafka-esque conspiracy to erase Juliana Hatfield's very real sister from existence. It was already amazing enough that someone had gotten on the radio with this great, weird, conflicted song about all the feelings that can come with having a sister -- love, anger, envy, longing, guilt, the weird dissonance that comes with knowing someone better than anyone else in the world but not really knowing them at all. And then someone was going to tell me that this sister was not real? It was too much. Everything that I knew was a lie.

But the music journalists of America were not lying -- not about that one thing, anyway. Juliana Hatfield, a person with no sister, had written an elegantly devastating song about the idea of having a sister, and she made it sound so real and lived-in that I believed every word. I have a sister, but she's nine years younger than me, while the sister of "My Sister" is presumably older than the narrator. When "My Sister" was on the radio, my sister was four, so I didn't have any real point of reference for Hatfield's song, either. Maybe that's the magic of "My Sister" -- just a whole lot of people with no big sisters imagining what it might be like to have one.

The revelation about the nonexistent sister was so shocking because "My Sister" comes across as such real, unvarnished communication. There's always artifice involved in music, in the act of translating thought into sound, but I didn't really understand that when I was 13. "My Sister" isn't a song with a direct thesis. It's a bunch of jumbled, contradictory thoughts flooding out at once. Juliana Hatfield sings those thoughts in a desperate, conversational yowl, and she does it while playing serrated-twinkle guitar riffs that sounded just slightly thornier than what I was used to hearing on alt-rock radio.

"My Sister" didn't stick around on the radio for so long that I got sick of it, and Hatfield never became a universe-conquering rock star. So the song sits right in a glorious little nostalgic sweet spot for me. It evokes big feelings and big memories without the weight of cultural canonization. To me, "My Sister" is a perfect, glittering example of what could happen in the alt-rock boom when it was really humming. It's partly because of who I was when the song came out, but it's also because it's a great fucking song.

In 2013, Kory Grow wrote a SPIN oral history about "My Sister," and let me tell you: If there was an oral history about every song in this column, my life would be a whole lot easier. Here's how Hatfield explains the fact that she wrote a song about her sister despite not having a sister:

I’ve always been in this sort of perpetual state of existential longing. I feel like something’s missing. I almost feel like I have a twin who died at birth but no one ever told me that the twin existed. And with this song, I was trying to explore the idea of a sister who I never had. In the beginning, that seemed like a really nice idea. I had two brothers, but I never had a sister. But then the song ended up being kind of sad. It was more of a longing for a sister who was never nice to me, or a relationship lacking the things that I wanted from it.

I guess I was thinking a little bit about my relationship with my two brothers and putting myself in the role of the sister. I was trying to see myself from their perspective. Maybe they thought I was aloof a little bit.

Perhaps Juliana Hatfield can't explain the inspiration behind "My Sister" in a very satisfying way because it's just one of those ineffable things that you can't explain. It's what she was thinking and feeling in the moment, and thoughts and feelings don't always make linear sense. In any case, as far as we know, Juliana Hatfield did not have a twin sister who died at birth. Hatfield was born in a Maine town called Wiscasset, but she grew up in the seaside Boston suburb of Duxbury, which she called "Deluxe-bury" in an early lyric. Her mother was the fashion editor at the Boston Globe, and I still think it's amazing that I was alive at a time when a regional newspaper might have a fashion editor. We've lost so many things.

As a teenager, Juliana Hatfield was a shy kid who was into writing poetry and mainstream pop music like the Police and Olivia Newton-John. On a dare, she started singing with the Squids, a cover band that her classmates had. One of the key inspirations for "My Sister" was an older girl named Meg, who was dating one of Hatfield's older brothers and moved in with the Hatfield family for a little while. Hatfield in that SPIN oral history: "It was so great. I never had anyone like that in my life, someone whose shoulder I could cry on and who I could talk to about my fears and my anguish. She also brought her record collection to my house, which really opened my eyes to a whole lot of bands." Meg introduced Hatfield to the legendary LA punk band X, and she fell in love with them. (X's highest-charting Modern Rock hit, 1993's "Country At War," peaked at #15.)

Meg also took Hatfield to her first all-ages show in the early '80s. You'll never believe this, but it was the Violent Femmes and the Del Fuegos. (The Violent Femmes' higheset-charting Modern Rock hit is 1991's "American Music," which peaked at #2. It's a 9. The Del Fuegos' only Modern Rock hit, 1989's "Move With Me Sister," peaked at #22.) The picture's starting to make a bit more sense, right? Meg wasn't Hatfield's sister, but Hatfield came to see her that way. Even with the detail about that first all-ages show, Meg didn't realize that she was the primary inspiration for "My Sister" until Hatfield wrote her memoir decades later.

Hatfield started going to college at Boston University, but then she transferred over to Berklee College Of Music. Hatfield was depressed and lonely at Berklee, and she developed a fascination with two other people, the couple John Strohm and Freda Love. But both of them were fascinated with her, too, so they all started a band together. After a few practices, they went up to the poet Allen Gisnburg after a reading and asked him to name their band, and he said that they should call themselves the Blake Babies, so that's what they did. The Blake Babies got started in 1986, and they self-released their debut album Nicely, Nicely a year later.

The Blake Babies fit right in with Boston's jam-packed college-rock universe. All three Babies moved into a Boston condo that Hatfield's mother owned, and it became a crash pad for local musicians. Thanks in part to that condo, the Blake Babies intersected with other Boston bands. For a while, John Strohm played in the Lemonheads, a band that'll appear in this column pretty soon, while lead Lemonhead Evan Dando played bass in the Blake Babies. Hatfield led the Blake Babies, singing fizzy-fuzzy power-pop jams with an acidic sweetness. They worked quickly, cranking out four albums in four years. When the indie label Mammoth Records launched in 1989, the Blake Babies became their flagship act. They never escaped cult-act status or landed on the Modern Rock chart, but their shimmering shamble-pop found a cult audience and a critical cachet. I've been taking my first real dive into the Blake Babies discography while working on this column, and there are a whole lot of gems in there.

The Blake Babies were very much a product of the American rock underground, just like Nirvana. In fact, Juliana Hatfield was so impressed with Bleach that she wrote a song called "Nirvana," which the Blake Babies included on their 1991 EP Rosy Jack World and which Hatfield later re-recorded as a solo track. The Blake Babies didn't sound anything like Nirvana, but they moved in the same circles. The Blake Babies broke up in 1991, just as Nirvana took off. John Strohm and Freda Love started a new band called Antenna, while Hatfield went into a period of deep depression. Those feelings went into Hatfield's solo debut Hey Babe, which came out on Mammoth in 1992.

For the most part, Hey Babe sounds like an extension of the gauzy garage-pop that Hatfield made with the Blake Babies, but it's a bit more streamlined and direct. Hatfield had help when making the album. Evan Dando played on a few songs, and so did underground-staple types like Mike Watt and John Wesley Harding. But Hatfield is the clearly her own dominant creative force. She plays bass and guitar on the LP, and she makes desperation sound dizzy and accessible and sometimes even fun. Her single "Everybody Loves Me But You" never reached the Modern Rock charts, but I definitely heard it a lot back in the day. That thing is a banger. If a song like that came out today, the music press would go into immediate hype-overdrive.

While she made Hey Babe, Hatfield also played bass and sang backup in the Lemonheads. Hatfield was a Lemonhead when they made 1992's It's A Shame About Ray, a genuine gold-selling surprise success. I don't want to get too deep into the Lemonheads because they're getting their own column soon, but there was a lot of fascination around Evan Dando and Juliana Hatfield. In interviews, Hatfield said a bit more than she probably should've said. She talked about struggling with eating disorders, and she claimed that she was a virgin when she was in her mid-twenties. People were not normal about this. Dando was probably the preeminent alt-rock hunk of the pre-Gavin Rossdale era, and nobody could believe that he and Hatfield could have a creative and professional relationship without fucking. When Hatfield appeared on the cover of SPIN in 1994, a month after Dando, the text on the cover was "Like A Virgin: Juliana Hatfield Gives It Up." Honestly, it's amazing that rock criticism still exists today, that all of my elders weren't just rounded up and thrown in jail.

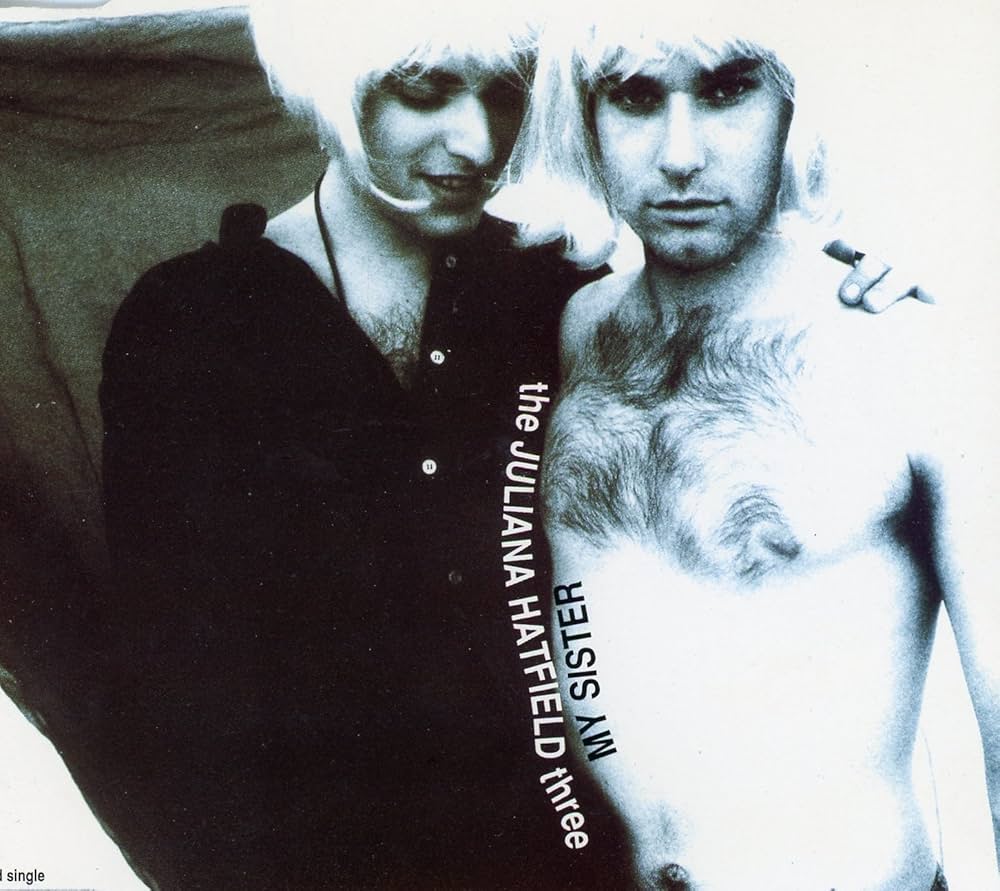

In 1992, Mammoth Records signed a joint-venture deal with Atlantic, an easy way for the major label to get into the next-Nirvana race. In 1993, Juliana Hatfield left the Lemonheads and put together her own band. Really, she already had a band. The Juliana Hatfield Three was just Hatfield's touring group, and it seems like she decided to switch over to the full-band billing on a whim. Bassist Dean Fisher was high-school buds with Hatfield in Duxbury. In that SPIN cover story, Hatfield says, "He had a crush on me in high school, and I had a crush on him, but we never told each other. We just kinda said hi in the halls." Been there, sister. Drummer Todd Phillips, not the Joker director guy, came from the Boston band Bullet LaVolta. I always thought of Bullet LaVolta as an undersung hair metal group, but they were apparently punkier than that. Maybe I just got them confused with the BulletBoys.

Hatfield wrote "My Sister" before Dean Fisher joined the band. (At the time, she was auditioning indie rock lifer Mary Timony for the bassist position.) Semi-famously, "My Sister" doesn't have a chorus, but this didn't bother anyone. Hatfield tells SPIN, "I was trying to write something catchy and accessible, but not in a crass, commercial way. I just came up with those four chords that are the verse, and then it sort of ended up not having a chorus." "My Sister" starts with a spiky, ominous riff before moving right into a wide-open jangle so bright and optimistic that it might snatch your breath away. The song doesn't need a chorus because the whole thing sounds like a chorus.

"My Sister" still kills me. Hatfield sings it with this warm, off-the-cuff grace. Thanks to her guitar-fuzz and the taped-together immediacy of the whole thing, the song is at least grunge-adjacent. Like a lot of the best grunge songs, and I guess also like the fictional sister, "My Sister" is inviting and forbidding at the same time. But the big difference between that song and grunge is that you can understand every word that Hatfield sings. She brings an absolutely heart-crushing emotional vulnerability to her delivery. The opening line is the kind of thing that sticks with you: "I hate my sister, she's such a bitch." You can tell that she means it, but you also tell that she means every other contradictory thing that she says over the course of the song.

On "My Sister," Juliana Hatfield sketches out a complicated relationship in a few quick strokes. The narrator thinks that the sister is a remote island who doesn't know that she's there, but she's also an aspirational figure. She has the greatest band and the greatest guy; she's good at everything and doesn't even try. Hatfield's narrator can't break through and get close to her sister, and she wants it so badly. She sings that she tried to scale the sister's metaphorical walls, but "lit a firecracker, went off in my eye," a stray shard of imagery that sticks with me decades later. With cutting specificity, Hatfield laments that her sister would've taken her to her first all-ages show -- the Violent Femmes and "the Del Foo-way-goooooes" but that it never happened. Instead, the sister disappears, and Hatfield's narrator doesn't know where she went. This always sounded terribly mysterious to me as a kid, but that stuff happens in real life. Important people pass through your orbit, and then they're gone. If you're a kid, you probably can't do anything about it. Hatfield sounds like a kid when she chants that she misses her sister as the song draws to a close.

"My Sister" is so sharp and immediate and evocative, and the song itself rocks so hard. From where I'm sitting, the early-'90s alt-pop wave doesn't get any better than "My Sister." Juliana Hatfield had plenty of competition; Boston-rooted contemporaries like Belly and the Breeders were putting out their own immortal hits around the same time. I absolutely love that bittersweet, elusive, playful, wounded crunch-pop thing that all those bands nailed so completely, and "My Sister" is one of the greatest examples of the form. Looking back today, it feels like a miracle that a song that tangled and intense and messy could just become part of my life when I was in middle school. Maybe that means that the monoculture was fraying, or maybe it was expanding enough that this kind of frayed voice could have a moment in the spotlight. Either way, I'm grateful that "My Sister" hit at the exact moment that it did. I needed that song.

Juliana Hatfield named her 1993 album Become What You Are after a Nietzsche quote, and she and her band recorded it with Scott Litt, a producer who's already been in this column for working on a bunch of R.E.M. songs and the Replacements' "Merry Go Round." Litt produced Become What You Are right after working on R.E.M.'s Automatic For The People and right before working on Nirvana's In Utero, so the man was on a serious run. Become What You Are is full of tart, sharply written jams, and "My Sister" is the best of them. Hatfield and her band made the "My Sister" video with future Junebug director Phil Morrison, and they did their best to restage the Police's "Roxanne" clip. MTV put the video into its Buzz Bin, and the song took off.

Juliana Hatfield didn't much like the attention that came with fame, especially with everyone asking her about being a virgin or dating Evan Dando. She said less and less in interviews, and she ended up in a lot of trend pieces about women in rock, a big fascination for magazines at the time. Melissa Ferrick, a Boston singer-songwriter who was on the same label as Hatfield and who was friendly with her band, released a reportedly rude "My Sister" answer song called "The Juliana Hatfield Song (Girls With Guitars)," which is supposedly about how Ferrick didn't want to be lumped into the same women-in-rock categories but which also has lines about how Hatfield doesn't even have a sister. I would've probably used "The Juliana Hatfield Song" in the Bonus Beats section below, but it doesn't even appear to be on YouTube. Even without hearing it, though, you can chalk that up as one more indication of how weird and frustrating alt-rock fame must've been. Once you level up from a tour band to a tour bus, everyone who ever knew you starts talking shit.

Ultimately, "My Sister" didn't exactly take off beyond the world of alt-rock radio and the MTV Buzz Bin. Become What You Are sold a few hundred thousand copies but stopped short of gold, and "My Sister" never crossed over to the Hot 100. Another Become What You Are song did scrape the bottom of the Hot 100, though. "Spin The Bottle," which oddly never made the Modern Rock charts, reached #97 after Ben Stiller included it on the Reality Bites soundtrack and directed its video. That's a good song.

In 1994, Juliana Hatfield played a lunch lady on an episode of The Adventures Of Pete & Pete, and she also took part in what I remember as my least favorite episode of My So-Called Life. She's a homeless girl who's dressed as an angel who turns out to be dead the whole time. It was cool seeing her on TV, anyway.

The Juliana Hatfield Three didn't last, and Hatfield's next album was the 1995 solo joint Only Everything. Lead single "Universal Heart-Beat" peaked at #5 on the Modern Rock chart and #84 on the Hot 100, and Hatfield hasn't been back on either chart since then. (It's an 8.) When the album came out, Hatfield's depression was bad enough that she cancelled some of her tour dates. She recorded another album called God's Foot that was supposed to come out in 1997, but Atlantic didn't hear a single, and the LP was shelved. Only a few songs ever came out. When the record leaked online later, it was all out of order, and Hatfield was pissed. She looked into buying her masters from Atlantic, but it would've been too expensive. A few years ago, Hatfield told Stereogum, "I never understood. They wouldn’t give them back to me, but they also didn’t release it. The label could have made money if they released it, or they wouldn’t have made money, but they maybe would have lost less."

Juliana Hatfield vented some of her frustrations with the major-label system on her 1997 song "Sellout”: "It's not a sellout if nobody buys it/ I can't be blamed if nobody likes it." She has been an independent artist ever since she split from Atlantic, and she's released a lot of music. Hatfield got back together with the Blake Babies, and they released another album in 2001. In 2003, Hatfield started a band called Some Girls with her Blake Babies bandmate Freda Love, and they released a couple of albums. Hatfield also got back together with the Juliana Hatfield Three, and they released another album in 2014. She's started bands and put out albums with Paul Westerberg and with Nada Surf leader Matthew Caws. Over the past few years, she's devoted entire tribute LPs to Olivia Newton-John, the Police, and ELO. Every new Juliana Hatfield record feels like a fun adventure.

For a while, Juliana Hatfield was regularly putting out records that she financed through the crowdfunding site PledgeMusic, which eventually went under. In her 2021 Stereogum interview, Hatfield told us about how she doesn't really like trying to market herself, and that's probably part of the reason that she never got hugely famous. When she did that interview, she was splitting time between music and occasional odd jobs. That's fucked up. Juliana Hatfield wrote "My Sister"; she should be rich forever. But even if she never gets rich, she still wrote "My Sister." None of her richer peers can say the same, whether or not they have actual sisters.

GRADE: 10/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's the time-capsule footage of Juliana Hatfield talking to Kennedy and playing an acoustic version of "My Sister" on MTV: