June 18, 1994

- STAYED AT #1:6 Weeks

In The Alternative Number Ones, I'm reviewing every #1 single in the history of the Billboard Modern Rock Tracks/Alternative Songs, starting with the moment that the chart launched in 1988. This column is a companion piece to The Number Ones, and it's for members only. Thank you to everyone who's helping to keep Stereogum afloat.

Rock critics love a narrative. Our whole job is the narrative. Without it, we've got nothing. We devote our professional lives to an arcane practice -- spinning stories out of pieces of music, extrapolating larger ideas from organized sound-patterns. Scenes? Subgenres? Biographical fun facts? That is our shit. Really, that's all this column is. When a rock critic encounters a band with no narrative, that poor slob can only flop around hopelessly, coming up with new hyphenated adjectives to describe guitar riffs. Or maybe that poor slob can come up with a narrative and impose it on the band.But the band has to give us something to work with.

Back when radio mattered, narratives were optional. If a band had a narrative, that wouldn't necessarily hurt them on radio. It might give DJs something to chat about in the 15 seconds between song identifications and commercial breaks, but any references to narrative were pure sideshow. The songs themselves were the real attractions. (In the spaces where radio still matters, narrative remains optional, and so do songs themselves. Radio stations will just keep playing the same 12 songs forever until the charts freeze into rigor mortis. It's crazy.) If a band had a funny name in the '90s, then that could be the narrative, as far as radio DJs were concerned. A critic might not be able to hang a magazine feature on the fact that a group of fairly anonymous guys from California freely chose to use the name Toad The Wet Sprocket, but a radio DJ was happy to riff on that name for a few seconds and then move on.

That band name really is the most interesting extra-musical thing about Toad The Wet Sprocket, a group with no scene or subgenre and very few biographical fun facts. In retrospect, we can do at least some historical work to situate Toad in moment when college-rock went pop and R.E.M. acolytes could slide right into adult contemporary rotation. Even then, though, it's sweaty work. The thing that made Toad The Wet Sprocket popular wasn't their name or anything else extra-musical. It was a series of songs that sounded right on the radio in that moment. I don't think Toad The Wet Sprocket have any classics, but they've got at least a handful of very good songs -- songs that can now transport me instantly back to my middle-school bedroom in the rare occasions that I encounter them in the wild. One of those songs is "Fall Down," which rocks slightly harder than the others and which became Toad's only #1 Modern Rock hit.

In the context of this column, Toad The Wet Sprocket fit neatly into a specific category. There's a bigger narrative to this whole ongoing project. Thus far, we've seen arty British bands ruling the alt-rock airwaves in the late '80s, and we've seen the rise of the grunge bands who gradually replaced them in the early '90s, as well as a few hints of what came after the grunge explosion. That's the big narrative. A game-changing new act comes along, shoots adrenaline into the system, and things change. That band's style slowly dilutes itself into everything else, and then things get sleepy until another game-changer comes along. Maybe that band will fade, or maybe it'll become an institution that sticks around forever. But even with all that rising and falling going on, there's still a persistent thrum of sincere white boys with jangly riffs who want to be R.E.M. That's a constant, and Toad The Wet Sprocket slot right in there alongside Cracker and Soul Asylum and the Gin Blossoms and early Live. Toad fit that mold better than most of those bands, all of whom had twisty histories. Toad didn't have that. They just had the sincere jangles, and maybe also the funny name.

Because I'm a rock critic, this particular column probably seems snooty as hell. It probably looks like I'm passing judgment on Toad The Wet Sprocket for having a funny name and a generic sound and nothing much in the way of historical context. Maybe I am. Maybe my position leaves me helpless to avoid snarking at any band that dared to find success without developing a cult of personality around themselves. But the thing is that Toad The Wet Sprocket had some really good songs. I've been doing my first-ever Toad deep-dive for the purposes of this column, and it leaves me thinking that Toad The Wet Sprocket didn't have many good songs; I'm finding their albums to be pretty leaden and uninspired. But that just means that Toad The Wet Sprocket were good at picking their singles, which is a hugely important part of the game.

Maybe every Toad The Wet Sprocket song is a grower. Maybe I'm doomed to find their albums boring because I'm just hearing them now for the first time. Maybe the singles imprinted themselves on me through the endless repetition of '90s radio rotation, and the deep cuts would hit me just the same way if I gave them enough time. I'm trying to be fair here. But time has done miraculous things for the Toad The Wet Sprocket songs that I remember from my adolescence. Those songs never made a huge impression on me back then, but simply by being in the air, they soaked up memories and images and feelings like a... well, a wet sprocket, I guess. Today, I hear "Fall Down," and I think it sounds pretty fucking good.

We might as well get the band name out of the way right up top, right? I don't have some dramatic reveal here. There's no suspense to build up. That name is a funny combination of words, but the members of Toad The Wet Sprocket didn't come up with it themselves. They took their band name from a fake band that Eric Idle mentioned in a Monty Python sketch. In "Rock Notes," from the Pythons' Contractual Obligation Album, Idle pretty much does the radio-DJ thing where you fill up a few minutes of airtime with news about bands. Idle's announcer calmly delivers the news that Rex Stardust, lead electric triangle player in Toad The Wet Sprocket, had his elbow removed after a tour of Finland.

Eric Idle later said that he found out that a real band took the name Toad The Wet Sprocket when he heard a radio DJ using their name, just as his fake radio DJ had once done, and he "nearly drove off the road." After the real Toad The Wet Sprocket got famous, they had a platinum plaque sent to Idle, and he wrote them a nice thank-you note. Well, shit. I just burned the one good anecdote. What the hell else am I going to do here? Talk about Toad The Wet Sprocket's music? I guess that's what I'm about to do here. In real life, Toad The Wet Sprocket didn't have an electric triangle player with an amputated elbow. They just had a bass player who kind of looked like George Lucas. Real life is always so much more pedestrian than even the most forgettable Monty Python skit, and it's usually not even the silly-walk kind of pedestrian.

The backstory, such as it is: Toad The Wet Sprocket got together in Katy Perry's hometown of Santa Barbara, California in the mid-'80s, right around the time Katy Perry was born. (My uncle just moved to Santa Barbara, but I've never been there, so the only thing about that place that really comes to mind for me is "Katy Perry's hometown." That's some rock critic brain disease right there.) The guys in Toad all went to high school together. Frontman Glen Phillips, the son of a physics professor, was younger than the others. He was just 15 when the band started, and he took his GED test early so that he could hurry up and get out on the road with the other guys. I wonder how he sold that to his dad. My dad was a college professor, too, and he would've locked me in a trunk if I tried to drop out of school so that I could tour with my 10th-grade band. That's pure speculation, though, since I didn't have a band in 10th grade, or in any other grade.

The Toad The Wet Sprocket guys became friends in the drama club at San Marcos High School, and they practiced in garages. None of them had ever been in a band before Toad. They naturally picked the band name as a joke, and it naturally stuck. Dean Dinning, the aforementioned George Lucas-looking bass player, is the nephew of Mark Dinning, the guy who had a #1 hit with the doomed high-school romance song "Teen Angel" in 1960, but I don't think that quite qualifies him for nepo-baby status. Toad's first gig was at an open-mic competition in 1986, and they lost.

Even after that initial devastating defeat, Toad The Wet Sprocket found some managers, and they released their debut album Bread & Circus in 1988. They produced the record themselves, and they only spent a few hundred bucks on studio time. At first, Bread & Circus only came out as a tape that you could buy in local record stores, but the band's managers sent it around as a demo. In 1989, Columbia signed Toad, and the label reissued Bread & Circus without any alterations. Bread & Circus is some real R.E.M.-clone monastic-jangle business. It didn't turn Toad into stars, but it got some burn on college radio. Their supremely depressing single "One Little Girl" made it to #24 on the Modern Rock chart.

In 1990, Toad The Wet Sprocket released Pale, their second album. Once again, they made it quickly and cheaply. Lone Justice bassist Marvin Etzioni signed on as their producer, and the LP got pretty much the exact same reception as Bread & Circus -- one song in the lower reaches of the Modern Rock chart, no real press, no real sales. In this case, the song that charted is the mandolin-laced "One Back Down," which I think is pretty good. It peaked at #27.

The first two Toad The Wet Sprocket albums are pretty standard versions of that era's sensitive American college rock. The same is basically true of their next LP, 1991's Fear. But Fear had the good fortune to come out about five months after R.E.M. released Out Of Time, when the commercial ceiling for sensitive American college rock was shooting skyward. They also spent more money on the record. It was their first time recording with the Scottish producer Gavin MacKillop, who'd worked with bands like General Public and the Straitjacket Fits. Lead single "Is It For Me" went nowhere, but Toad followed it up with "All I Want," a gentle power-pop number that the group almost left off the album. "All I Want" never became a big alt-rock radio hit; it peaked at #22. But pop radio latched onto "All I Want," and the song went all the way to #15 on the Hot 100. Suddenly, Toad had a hit.

In a 2018 Stereogum interview, Glen Phillips talked a lot about the mental weight of landing a surprise hit in the early '90s. He says that Toad still thought of themselves as an indie band, even though they'd been on Columbia for virtually their entire run: "Having a hit doesn’t really work if you’re an indie band. It’s counter to the idea... We really thought of ourselves in a certain way, and when we put out 'All I Want' it was really strange for us. We were deeply concerned that the right people liked us, and we lost our credibility." Sometimes, Phillips says, Toad would refuse to play "All I Want" live, though that only happened a few times: "Uhh, we mostly played it, but we were kind of jerks about it."

Toad were a little less unsettled when another Fear song, the lightly grandiose ballad "Walk On The Ocean," took off. That's the song that immediately pops into my head when I see the words "Toad The Wet Sprocket." I like that track. It's got ponderously meaningless lyrics about flesh becoming water and wood becoming bone, but I like the way that Glen Phillips' voice floats over the strings and accordions. It's one of the prettiest R.E.M. bites that I remember hearing on the radio back when R.E.M. biters were doing big business. "Walk On The Ocean" didn't even make it onto the Modern Rock charts, but pop and adult contemporary radio played it, and it reached #18 on the Hot 100. Three years after its release, Fear went platinum.

Toad The Wet Sprocket toured hard behind Fear, and they dropped loose tracks on the soundtracks of Buffy The Vampire Slayer (the 1992 movie, not the TV show) and So I Married An Axe Murderer. When they went back into the studio with Gavin MacKillop, they felt like they had a little more to prove. In that Stereogum interview, Glen Phillips describes Dulcinea, the next Toad album, as "edgier, surprise." The band had done a ton of touring and gotten better onstage, and they wanted something without all the strings and fripperies of Fear. They wanted to make an album that they could play live. Maybe that's why lead single "Fall Down" rocks so hard.

I don't remember thinking too hard about Toad The Wet Sprocket or "Fall Down" in 1994. If I did, though, I would've been pleasantly surprised. There's no way that any radio listener who'd been exposed to "All I Want" and "Walk On The Ocean" could've identified "Fall Down" as a Toad song in a blind taste test. It's not like Toad suddenly turned into Slayer or anything, but "Fall Down" brings a level of venom that I simply don't hear in any of their other songs. It sounds like the Byrds when they were at their angriest, and that's a great blueprint for a band to use.

"Fall Down," like Toad's previous big singles, is still plenty pretty. I like the way the other guys' harmonies well up under Glen Phillips' voice, and I like the way the guitars sparkle and glide. After the chorus, they add in some treble-drunk riffage that almost takes things into surf-guitar territory for a few seconds. (This was the summer of Pulp Fiction, so surf-guitar music was about the coolest that it had been since 1963. We'll see a bit more of that in next week's column, too.) For all of its layered composition, though, "Fall Down" is a tight and terse three-minute rocker that is plainly not written for adult contemporary radio. Maybe that's why it caught on among the modern rock radio programmers who had previously been so resistant to Toad's charms.

Glen Phillips co-wrote "Fall Down" with Toad guitarist Todd Nichols. In a 2022 Songfacts interview, Phillips says that they wrote "Fall Down" before they released Fear and that it was about a girl who they knew in high school. Phillips says the girl "was rebelling against and living out people's worst expectations of her. I think when you're misunderstood there's an urge sometimes to self-destruct as a form of rebellion." I knew kids like this in high school, and I'm willing to bet that you did, too. Sometimes, people perceive rebellion when it's really just self-destruction, or someone is just struggling. But the scenario repeats itself again and again: Someone who seems to have a bright future goes down spiraling so quickly that it leaves everyone's heads spinning.

"Fall Down" kicks off with a fast, circular riff, and Glen Phillips starts singing at the moment that the drums kick in. Without getting too specific, he describes a sense of desperation: "She said, 'I'm fine, I'm OK,' cover up your tremblin' hands/ There's indecision when you know you ain't got nothing left." The girl in the song is trying to have a good time, but that good time never lasts. She's in a bad place: "She hates her life, she hates her skin, she even hates her friends/ Tries to hold on to all the reputations she can't mend." Gradually, she exhausts all her resources, until nobody will show up and pay her bail after she gets arrested. The chorus asks when we will fall down, and the obvious answer is that it's already happening. Near the end of the song, Phillips implicates himself in the girl's downfall: "For a good friend, I was never there at all." Maybe that's where the song's anger comes in. Maybe it's just Phillips snarling about his own failures, about how he couldn't or wouldn't help this girl get her life together.

Tons of the songs that appear in this column come from people like that girl -- the ones who were in it, who were chronicling their own downfalls for the world to hear. The members of Toad The Wet Sprocket never come off that way. They strike me as career-minded craftsmen who weren't too visibly invested in the paradoxes inherent to '90s alt-rock stardom. "Fall Down" is a song about struggling, but the person struggling isn't the narrator. He's watching someone else go through it, and he's mad at himself for letting it happen. I know how he feels. I've watched so many friends fuck their whole lives up. You try to tell yourself that you did everything you could, that it's not your fault, but you never fully believe it. "Fall Down" came out around the time that I finished eighth grade, and that was already happening in my life back then. I can't say that I understood the song at the time, but maybe that self-lacerating feeling informed the track's jangly, determined forward motion.

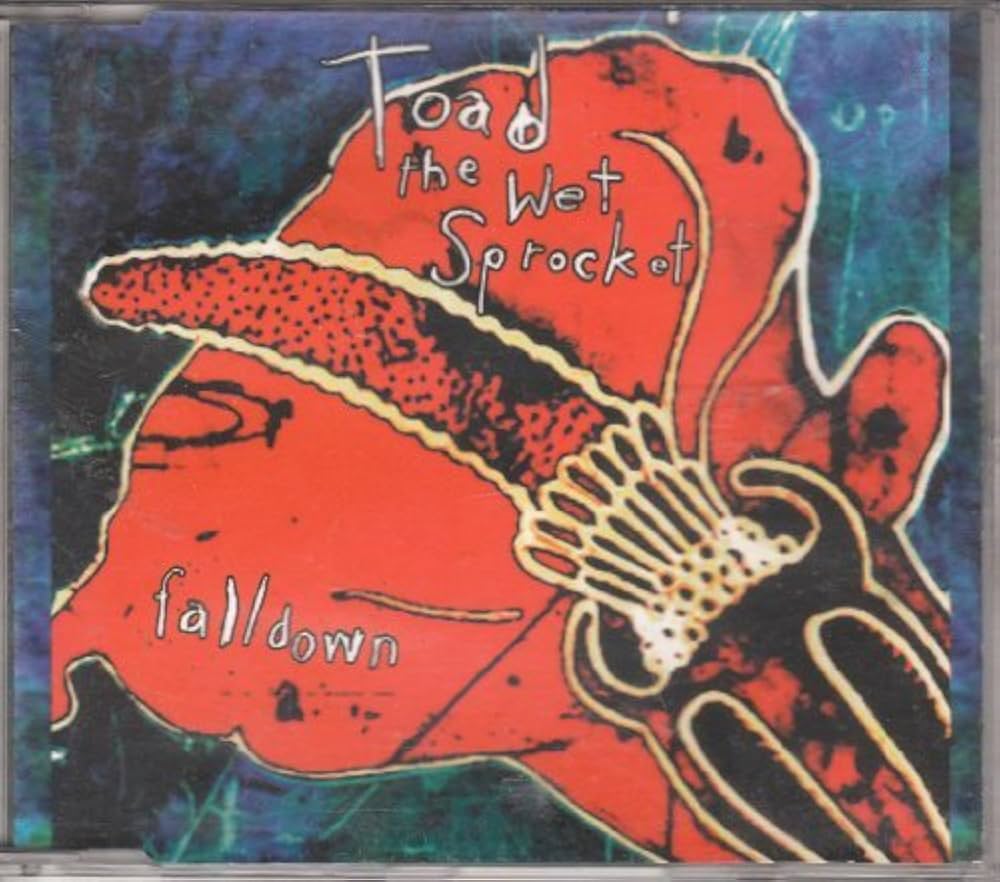

I don't hear the same urgency in any of the other songs on Dulcinea, an album named after the idealized lady from Don Quixote. Toad's follow-up single "Something's Always Wrong" finds them right back in pseudo-R.E.M. balladeer mode. It's a pretty good example of that form, and I like its fake-infomercial video, but it doesn't have much of the fire that they brought to "Fall Down." "Something's Always Wrong" reached #9 on the Modern Rock chart, giving Toad their second and final top-10 hit. (It's a 6.) Both "Fall Down" and "Something's So Wrong" made it onto the Hot 100, too, though they charted lower than the Fear singles -- "Fall Down" at #33, "Something's So Wrong" at #41. Toad never made the Hot 100 after that, either. Dulcinea went platinum, and I saw its handpainted-orchids cover art in a lot of used-CD racks. When I see the image today, I can almost smell the dust in the air.

In 1995, Toad The Wet Sprocket released In Light Syrup, an odds-and-ends collection that went gold, and reached #20 on the Modern Rock chart with "Good Intentions," a Fear outtake that they released on the Friends soundtrack. That's a pretty good song. In 1997, Toad followed Dulcinea with their next LP Coil. Lead single "Come Down" feels like an attempt at another rocker like "Fall Down," and it doesn't quite get there. That song peaked at #13, and it was the last time that Toad were on the Modern Rock chart. Coil didn't sell as well as Toad's previous two albums or even In Light Syrup, and Toad The Wet Sprocket broke up in 1998. Phillips told Rolling Stone, "It felt like if we stayed together much longer, the tensions would hurt both the music and our friendships."

That kind of thing used to happen all the time. One album misses, so the members of the band decide that's the end of that, time to try something else. In this case, they all tried something else. Glen Phillips released his first solo album, the annoyingly titled Abulum, in 2001, and he cranked out a bunch of others after that. The other guys started a new band called Lapdog and released a couple of LPs. Even when they were broken up, though, Toad The Wet Sprocket weren't really broken up. They reassembled in 1999 to re-record their old song "PS" as a bonus track for a greatest-hits collection, and they started playing the occasional reunion gig as early as 2003. They went off on a full US tour in 2006, and they've basically been back together ever since.

Toad The Wet Sprocket used crowdfunding to raise the money to release their 2013 reunion LP New Constellation, and they came out with another one called Starting Now in 2021. Glen Phillips still puts out occasional solo albums. Toad continue to tour, mostly with other '90s and '00s bands who made hits but aren't considered canonically important. Later this year, they're hitting the road with KT Tunstall and Vertical Horizon, which seems about right. Toad's music was always pretty comforting, and it's comforting to know that they're still out there, making livings for themselves. I never loved any of their songs, but I liked a bunch of them just fine, and they never got popular enough to become irritatingly omnipresent. They were a working band then, and they're a working band now. That's not a bad legacy. They topped the Modern Rock chart exactly once, spanning the divide between two generationally important pop-punk breakthrough hits. "Fall Down" doesn't have a place in the history books like those two tracks, but it goes a lot harder than I remembered. That's not a bad legacy, either.

GRADE: 8/10

BONUS BEATS: In Drop Zone, a 1994 action flick about a US Marshall who goes undercover to infiltrate a gang of Point Break-style thrill-seeking drug smugglers, "Fall Down" soundtracks a scene of stunt-doubles skydiving. Wesley Snipes doesn't necessarily strike me as the type of guy who would happily jump out of a plane to some Toad The Wet Sprocket, but director John Badham evidently feels differently. Here's that scene:

THE 10S: Blur's bouncy, energized frustrated-romantic singalong "Girls & Boys," a lament about meaningless hookups that must've soundtracked so many meaningless hookups, peaked at #4 behind "Fall Down." Right now, I'm looking for girls who are boys who like boys to be girls who do boys like they're girls, who do girls like they're boys, who know that this song is a 10.